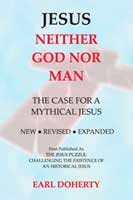

This is partly in response to “mythicist quote of the day”

Allow me to explain why I think so many arguments for the historical Jesus are based on an assumption of historicity.

Firstly, when I quote Sanders in this respect, it is not because I am faulting Sanders’ arguments for starting with this assumption. I still am a little bemused that my remarks were even seen as controversial. I thought the assumption was obvious, and that what Sanders was doing was arguing for motives and character of Jesus, and even for what we might think were some things he is more likely to have done, given the constraints of the Gospel narrative and what we know of historical realities of the time. All of this assumes an historical Jesus to begin with, and through which to interpret the Gospels. It does not even claim to be an argument for the historicity of Jesus per se.

Why my posts on E. P. Sanders

The reason I have been addressing Sanders is because his work, Jesus and Judaism, was recommended by James McGrath as a challenge to those who argue for a mythical Jesus. He challenged anyone to engage a work like this and come up with different conclusions. The context implied that he was meaning it would be unlikely for anyone to deem as unhistorical what Sanders argued was indeed historical. And the reason for this was, as I understood the original challenge, the methodology of Sanders, including his criteria for authenticity.

So I have been discussing Sanders’ work in particular in the context of those who use it as a basis for the claim that we have clear and strong evidence for the historicity of Jesus. As far as I can see Sanders nowhere addresses any methodology for establishing the historicity of Jesus. He does address methodology for assessing what is the likely character or motive or saying or action of the historical Jesus. So his methodology is built upon the assumption of an historical Jesus.

Responses to the challenge

In response to James’ challenge I first addressed Sanders’ own first point, the Temple Action of Jesus. I engaged Sanders’ arguments here, and demonstrated, I think, that an alternative to historical authenticity certainly is most plausible. (I address more detailed arguments of Sanders for the authenticity of this incident at the end of this post.)

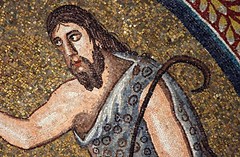

Next, I responded to some very strong claims by Sanders about certain details of John the Baptist. Sanders claimed that even John’s dress (along with other details) was a detail that “correctly pass unquestioned in New Testament scholarship”. I attempted to show, again in response to James’ challenge, that such a claim by a scholar like Sanders can be addressed and a different conclusion reached.

James’ responses to my efforts

James has since responded that I did not disprove the historical existence of John the Baptist. But that was not my argument, and is not central to any case for the “mythical Jesus” that I know. I had taken up the challenge to address a scholar like Sanders and demonstrate that it is possible to disagree with what Sanders himself argues is historical.

James has also since said that he does not see the points of my posts on Sanders. So it appears my taking up his challenge has been in vain at least from his perspective.

The assumption of historicity implicit in Sanders

But back to the specifics on Sanders and assumptions of historicity. Here is what convinces me that Sanders is not attempting to address the historicity of Jesus as such, but rather assumes his historicity:

We start by determining the evidence which is most secure. There are several facts about Jesus’ career and its aftermath which can be known beyond doubt. Any interpretation of Jesus should be able to account for these. (Jesus and Judaism, p. 11)

Here Sanders is stating that he is attempting to do no more than start with “facts about Jesus’ career . . .”. His intention is to use these facts as the basis for his “interpretation of Jesus”. His intent is to “account for” the “facts of Jesus’ career” in order to interpret Jesus.

To start with what one thinks are facts about one’s career is to assume historicity before one starts. To use a simplified analogy, I can apply the same analysis to Hamlet to interpret Hamlet. In that case my assumption is that he is a fictional character. But the point is that my ensuing “exegesis” of Hamlet does not itself verify that assumption of fictionality. It builds on it. Ditto for any exegesis of any text.

Sanders further acknowledges that his “facts about Jesus career” are not “facts” in the normal sense of what we mean by “facts”. Facts are normally defined as data on which everyone can agree. They exist quite independently from respective interpretations of them. (Okay, now you know I am not a postmodernist.) But Sanders says of his list of “facts” that can be known “beyond doubt”:

I do not regard any items in the following list as dubious, but some may. (p.357, note 19)

The almost indisputable facts, listed . . . are these: (p. 11 — and I listed these in my previous post).

This tells me that what are said to be facts about Jesus are open to challenge as facts. They are not facts in the sense that “Caesar crossed the Rubicon” or “Sophists appeared teaching in Athens around the fifth century bce” are facts. (Hence my first post to challenge the first of the “facts” Sanders discusses — the Temple Action.)

So we have two levels of “facts” to deal with here. Sanders begins by assuming that there is a historical Jesus. On this assumption he can assert that there are certain facts about what this Jesus did. The next level of “fact” is an exegetical argument based on this assumption. It is at this level that challenges begin to appear. My question is, why only at this level?

Historical methods

James has asked for historical methods that are used by nonbiblical scholars. The principle set of methodologies applied and questions asked by (nonbiblical) historians began with Leopold von Ranke. Others like E. H. Carr have moved things along a bit since von Ranke, but many of the basics still apply. This is where the ‘minimalists’ come in. Lemche discusses methodology at some length with reference to von Ranke. “Minimalist” methods have been castigated by some as overly sceptical, but those making the criticism seem not to realize that this is the standard approach to documentary and other evidence in nonbiblical history. Rather than repeat von Ranke’s relevant points, with Lemche’s application of them, in another context, I have discussed them previously here. The point, and related discussions of historical method and circular arguments, has already been addressed in a previous reply to James.

The key point is the need for external controls in order to establish the historicity of a narrative. They do not exist for the Gospel narratives, as even Albert Schweitzer stated, and as I’ve quoted often enough here but here it is again:

Moreover, in the case of Jesus, the theoretical reservations are even greater because all the reports about him go back to the one source of tradition, early Christianity itself, and there are no data available in Jewish or Gentile secular history which could be used as controls. Thus the degree of certainty cannot even be raised so high as positive probability. (Quest, p.402)

James has also said that New Testament scholars are obliged to use exegesis of texts as their methods for deciding what is historical fact and what not for the simple reason that other evidence is too scarce.

But is it valid to water down the methodologies if the required evidence on which they rely does not exist?

We lack the evidence required to establish the historicity of the Gospel narrative. It does not follow that it is therefore okay to assume historicity and just begin analyzing the texts as if there is some historical core to begin with. I read Josephus’s writings as history because I have reasons external to their text to have some confidence in their value as history. There is truly both independent (external controls) and multiple attestation of the events he writes about.

And problem of assuming historicity of the narrative is highlighted in another context (re the evidence of Papias) but I believe it also applies here:

The history of classical literature has gradually learned to work with the notions of the literary-historical legend, novella, or fabrication; after untold attempts at establishing the factuality of statements made it has discovered that only in special cases does there exist a tradition about a given literary production independent of the self-witness of the literary production itself; and that the person who utilizes a literary-historical tradition must always first demonstrate its character as a historical document. General grounds of probability cannot take the place of this demonstration.

It is no different with Christian authors. In his literary history Eusebius has taken reasonable pains; as he says in the preface he had no other material at his disposal than the self-witness of the books at hand. Not once was he able to say anything about the external history of the works of Origen, in which he was genuinely interested, apart from what he found in or among them.

And if in the case of authors who as individuals and sometimes as well-known personalities stood in the glare of publicity there is so little information about their production, how much more is this not the situation in the case of the Gospels, whose authors intentionally or unintentionally adhered to the obscurity of the Church, since they neither would nor could be anything other than preachers of the one message, a message that was independent of their humanity?

There is not even a shadow of a hope that their ever existed any trustworthy information about the way in which the Gospels came into being: the Christians of antiquity had other cares than to search out and preserve the history of the inscripturation of the Gospels, and when Gnosticism forced this concern upon them they filled the vacuum with inventions of their own as Gnosticism did before them.

This is from an academic paper delivered in 1904 by E. Schwartz: “Uber den Tod der Sohne Zebedaei. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Johannesevangeliums” (= Gesammelte Schriften V, 1963,48-123). It is cited in a 1991 chapter by Luise Abramowski titled “The ‘Memoirs of the Apostles’ in Justin” pp.331-332 published in “The Gospel and the Gospels” ed. Peter Stuhlmacher. I have broken up the paragraph for easier reading. Italics are original.

Further statements by Sanders demonstrating the assumption of the historicity of Jesus

Continue reading “Assumptions of historicity (in part a response to James McGrath)”

Like this:

Like Loading...