An argument has appeared on the earlywritings forum proposing that an early form of the Book of Deuteronomy was produced in the Persian period — more specifically, in Persian period Samaria.

It is mid-semester break for me and the scholarship relating to Persian period writings in Yehud and Samaria is still fresh in my mind (see the previous two posts) so here’s my chance to offer a critical review of a few details.

Archaeologist Yitzhak Magen’s dogmatic declaration that archaeological excavations “prove unequivocally that the temple on [Mt Gerizim] was built in the middle of the fifth century BCE” (before Nehemiah’s presumed arrival in Jerusalem) is quoted uncritically. Ironically later in the discussion Peter Kirby quotes Gary Knoppers who clearly responds to Magen’s published evidence with a measure of equivocation — Knoppers is not the only scholar to observe that the actual evidence presented is by no means definitive and could point to a shrine or altar rather than a temple. Magen’s quote is presented without any apparent awareness of the entirely circumstantial nature of Magen’s evidence and the doubts raised about his interpretations in the scholarship. (As for me, I simply don’t know if there was a temple on Mt Gerizim in the Persian period but as I will explain below, if there was, in the context of other evidence it would actually pose a problem for the argument that Deuteronomy was a product of the priests of such a temple. )

Magen’s dogmatic quote is followed by Diana Edelman’s conclusion that “it is more logical to assume” a Temple was constructed at Jerusalem in the Persian period in the time of Nehemiah — after Magen’s claim that the Samarian temple was erected before then.

The significance of this chronology for Peter K is that since the Mt Gerizim temple was constructed before the Jerusalem temple, then there was hope — as we find expressed in Deuteronomy — that this would be the sole and only temple for “Israel”. (PK does appear to assume the name “Israel” designated the region of Samaria at this time.)

[Unfortunately Peter concludes this section of his argument by misapplying a quote from C. Behan McCullagh’s Justifying Historical Descriptions. PK’s argument thus far is, he notes, one that “seems like the best explanation” and “in accordance with the way historians use such arguments, no more is implied than that ‘it is likely to be true'” — but adds that there remains “some reasonable doubt about this explanation” and a better explanation might come to his awareness some time. — McCullagh wrote that arguments to the best explanation are far from conclusive (p. 26) and his point about the kind of argument that is “most likely to be true” he applied only to those arguments that meet all 7 conditions that are required for us to justify belief — such as “the battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18th June 1815, and there can be no doubt who won the battle.” But it was encouraging to at least see an effort to apply a historian’s discussions of historical method here.]

Another encouraging point was to see a reference being made to archaeologist Israel Finkelstein’s “Black Hole” paper in which he emphasizes the lack of evidence in Yehud (Persian period Judah/Judea) for the kind of scribal culture necessary to produce any of the biblical writings. This detail coheres with Peter Kirby’s case for Deuteronomy being in an early form as a pro-Samarian text, one that justified the Samarian temple on Mount Gerizim — not a pro-Jerusalem document. The Finkelstein point is followed by a copy and paste of a full 12+ pages of Gary Knopper’s chapter in Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period that notes:

- the demographic strength of Samaria (compared to the low demographic situation of Yehud) in the Persan period — and the “flourishing” of the Samarian economy up until the early Hellenistic period.

- Hebrew script was used alongside Aramaic — though the supporting citations Knoppers applies here greatly qualify that statement.

- Most names of the period were Yahwistic.

- Cultural exchanges existed among Jews of Elephantine, Yehud and leaders of Samaria.

- Recent excavations “suggest” that “some sort of sanctuary or temple existed on Mt. Gerizim”.

This is followed by other indicators of the pro-Samarian interest of Deuteronomy, including a reference to a 2011 article by Stefan Schorch (compare my own discussion of a Schorch paper) — and arguments based on archaic Hebrew. No reference is made to controversies related to the linguistic arguments — see reference #12 in an earlier post.)

Finally, reference is made to the Yahwist temple at the Persian period Judean colony in Egypt at Elephantine. For PK, this colony followed “pro-Judean tradition” rather than Samarian according to correspondence discovered at the site. He appears to be unaware of Gard Granerød’s Dimensions of Yahwism in the Persian Period where we read:

Finally, the [Elephantine] community’s orientation towards Jerusalem and Judah suggests that the community considered itself affiliated with Jerusalem and Judah, perhaps as a diaspora community. At least two official letters written to Judah and Jerusalem are known. . . . The letters to Jerusalem and Judah were written against the background of the conflict with the Egyptian priests of Khnum and the local Persian administration in Upper Egypt. Assumedly, the conflict about the temple of YHW sharpened the community’s identity as Judaeans by providing an impetus to reconfirm its ties with the homeland, Judah. However, regardless of whether this was the case or not, the Elephantine Judaeans did not only orientate themselves towards Judah and Jerusalem; they also maintained contact with the Sanballat dynasty in Samaria (A4.7:29 par.). The Elephantine Judaeans received assistance from Samaria by means of a statement. The statement was given by a representative of the Sanballat dynasty in Samaria together with the governor of Judah (A4.9). Regardless of what implications this cooperation between Samaria and Judah may have for the political history of the provinces of Judah and Samaria, the point here is that the Elephantine Judaeans, by also orienting themselves towards Samaria thus displayed a special relationship with Samaria, a relationship that in turn seems to have been confirmed by the ruling dynasty in Samaria. (p. 32)

Here PK overlooks what might be the most damning detail against the plausibility of Deuteronomy being a product of Persian period Samaria. That fact that most personal names found were Yahwistic, the evidence for at least a shrine of Yahweh in Mt Gerizim and assuming a Temple to Yahweh somewhere in Samaria at the very least, — all of that data needs to be studied in the context of contemporary Yahwistic practices, not interpreted through the text of Deuteronomy itself. It is the date of Deuteronomy that is in question here — not the date of Yahweh worship.

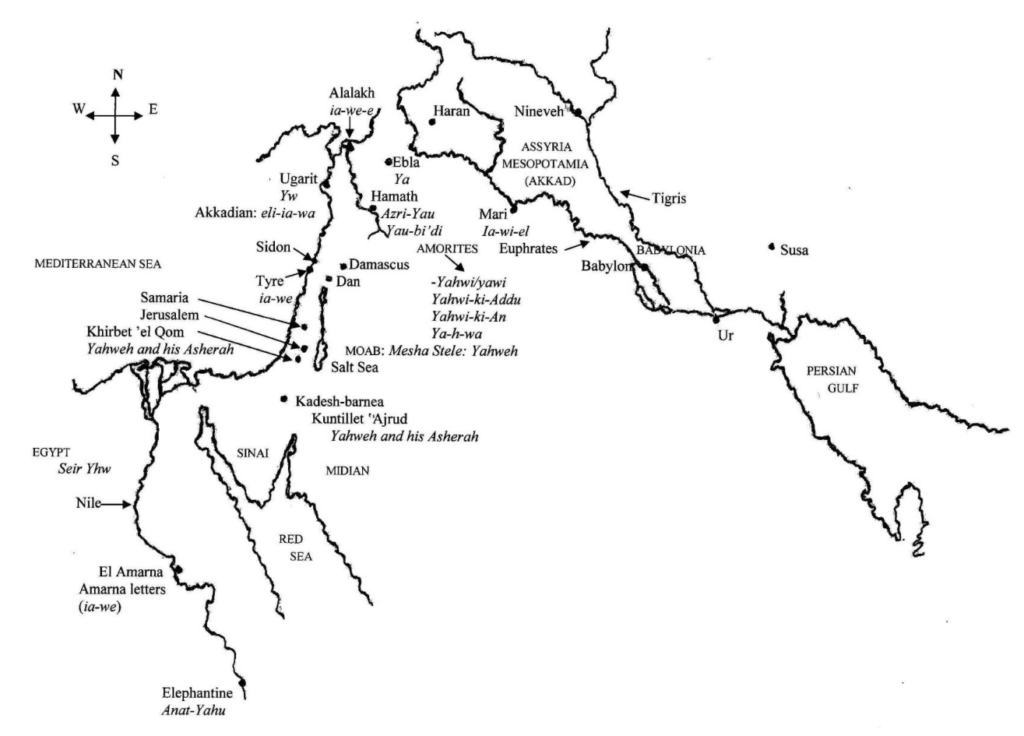

The cult of Yahweh or of some form of that name is found throughout the Levant. It is not unique to Samaria or Judea.

The Elephantine finds demonstrate that the cult of Yahweh followed practices that were alien to the precepts we find in Deuteronomy. The simple fact of the existence of a temple to Yahweh in Elephantine undercuts the notion that priests of Yahweh (see the above quote for cordial relations between Samaria and Elephantine) demanded a single place of worship for Yahweh. Further, Yahweh was worshipped alongside other deities, including his wife. See the linked references in the previous post. It is not until the Hellenistic period that archaeology locates specifically “biblical” precepts being embraced by communities in Palestine.

As for Russell Gmirkin’s thesis of a Hellenistic date and Alexandrian provenance for the Pentateuch, including Deuteronomy, it remains untouched by the above criticisms and coheres more neatly (according to McCullagh’s principles of sound historical argument) with both the archaeological and textual witnesses.