If the Old Testament books were not written before the Hellenistic era as a number of scholars have argued and as I have posted about for some years now, why would their authors have chosen a very favourable Persian empire as the narrative setting of the restoration of Judea after the Babylonian exile? We know Persia and the Greek states were enemies, after all.

One may object that the narrators had little choice but to choose the Persian period for the release of the Babylonian exiles simply because the Persians did historically replace the Babylonian empire and they were historically tolerant towards other religions. It would have been difficult to place the return from captivity as late as Hellenistic times if the story were to have any credibility at all. But why depict the Persians as being so benevolent towards the Judeans? The account of the exodus from Egypt proved that one could create a high drama in a tale of escape to freedom if one introduced a hostile ruler. Besides, the Persians were not in fact as magnanimous as the Bible has portrayed them. In reality, the Persians continued the mass deportations that Assyrians are infamous for.

Cyrus’ clemency towards the subdued nations must not be exaggerated. The massacre among the Babylonians after the battle of Opis has already been mentioned.* The Nabonidus Chronicle mentions how he looted the Median capital Ecbatana after he had captured it. In 547, Cyrus killed the king of Lydia and Lydians, Phrygians, and Urartians were probably deported to Nippur.185

185 The Murashû archive provides evidence that deportees from Lydia, Phrygia, and Urartu were settled in Nippur. . . .

Later Persian kings also deported people.

(Van der Spek 256, 258)

Similarly for Cyrus’s “religious tolerance”:

The idea of Cyrus as the champion of religious tolerance rests on three fundamentally erroneous assumptions. In the first place, it rests on an anachronistic perception of ancient political discourse. In antiquity, no discourse on religious tolerance existed. Religion was deeply embedded in society, in political structures, in daily life. . . .

Secondly, it is too facile to characterize Cyrus’ rule as one that had ‘tolerance’ as its starting point. Although it is indeed possible to describe his policy as positively pragmatic or even mild in some respects, it is also clear that Cyrus was a normal conqueror with the usual policy of brutal warfare and harsh measures. . . .

Thirdly, the comparison with Assyrian policy is mistaken in its portrayal of that policy as principally different from Cyrus’. . . .

(Van der Spek 235)

There is no contemporary evidence outside the Bible testifying to a Persian policy of deliverance for the Judeans. The archaeological evidence is clear: during the Persian era both Judea and Samaria were polytheistic societies (Yahweh being the chief god but not the only god) and sacred sites were multiple (not centralized in Jerusalem). The previous link will take you to several explanatory posts. See also the post on Yonatan Adler’s research demonstrating the “late origins of Judaism“. The Persians were no more tolerant of the Jewish religion than any other ancient power.

Yet Persia holds pride of place in the narrative background to the religion of the Bible.

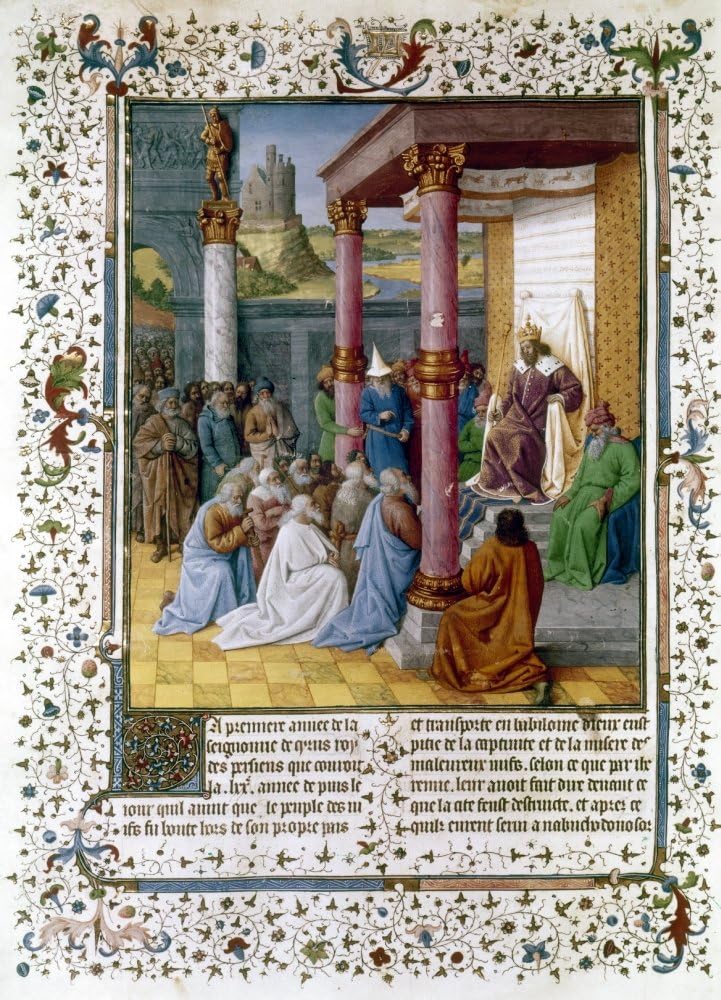

According to the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, the Persian rulers from Cyrus to Artaxerxes allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem, and helped with the building of the second temple. Jean Soler believes that this era saw the ‘invention of monotheism’ as the influence of Persian religion would have led the Jews to consider their regional god, Yahweh, as a unique god who alone created the universe. Soler thinks this invention was made after the writing of the Bible, when it became a national tradition. I disagree with Soler’s position as it still speaks from the perspective of religious evolutionism in that it fails to understand that the Bible is not a primitive literary work; rather, it was written directly under highly philosophical influences—mainly that of Plato. Moreover, this evolution of religion towards monotheism is actually part of the biblical narrative; in a world where polytheism and sin ruled, a pious people and their ancestors came to discover the only god. Once again, interpretation is a new version of the myth. Most scholars still paraphrase the divine revelation, always later in chronology, but the Persian era is kept as the ultimate end-point. (Wajdenbaum 38)

The authors of Chronicles, Isaiah and Ezra certainly give the Persian king Cyrus the highest praise as God’s anointed and as the restorer of the Judeans to their “homeland”. I wrote about the origin of the Cyrus-Messiah myth not so long ago. But if we accept the influence of Hellenistic literature (Apollonius of Rhodes, Berossus, Euripides, Herodotus, Hesiod, Homer, Manetho, Plato, Xenophon . . . . ) on the Pentateuch and other biblical texts, the question inevitably arises: why do the Persians get such good press?

Personally, I found myself wondering if Persia was chosen as the matrix for a resurgence of biblical religion in an effort by some biblical authors to implicitly rebut their intellectual captor, Hellenism. But no, the answer is surely simpler than that. Returning once again to Plato’s Laws (a work that others have seen as highly influential on both biblical narratives and laws), we read:

ATHENIAN: Hear me, then: there are two mother forms of states from which the rest may be truly said to be derived; and one of them may be called monarchy and the other democracy: the Persians have the highest form of the one, and we of the other; almost all the rest, as I was saying, are variations of these. Now, if you are to have liberty and the combination of friendship with wisdom, you must have both these forms of government in a measure; the argument emphatically declares that no city can be well governed which is not made up of both.

CLEINIAS: Impossible.

. . . .

ATHENIAN: Hear, then:−−There was a time when the Persians had more of the state which is a mean between slavery and freedom. In the reign of Cyrus they were freemen and also lords of many others: the rulers gave a share of freedom to the subjects, and being treated as equals, the soldiers were on better terms with their generals, and showed themselves more ready in the hour of danger. And if there was any wise man among them, who was able to give good counsel, he imparted his wisdom to the public; for the king was not jealous, but allowed him full liberty of speech, and gave honour to those who could advise him in any matter. And the nation waxed in all respects, because there was freedom and friendship and communion of mind among them.

CLEINIAS: That certainly appears to have been the case.

(See also the R.G. Bury translation along with book and line citation at perseus.tufts)

The very notion that in the time of Cyrus the Persians possessed the purest form of an ideal monarchy, the type of monarchy that could confidently give freedom to its subjects, was a myth perpetuated in Plato’s Laws. Another genre introduced in the Hellenistic era was the biographical “novel”, such as we find in the Book of Nehemiah. Should one further be reminded of the freedom with which Nehemiah (and later, Esther) conversed with remarkably friendly Persian kings. Those later incumbents to the throne fell far short of Cyrus’s beneficence, of course, and Plato went on to explain why such an ideal could not be maintained.

(If I have read this same point somewhere in work by Philippe Wajdenbaum or Russell Gmirkin I do not recall doing so, although both scholars are responsible for my train of thought and interpreting this passage in Plato as a rationale for Persia’s key role in the narrative of the Judean restoration.)

Continuing in Laws, Plato has his Athenian speaker explain why later Persian kings fell short of the ideal said to be embodied in Cyrus. While Cyrus was busy fighting to build his empire his sons were left to the care and instruction of women and eunuchs. This was sufficient to explain the flawed characters of Cyrus’s successors. Kingship ideals were somewhat restored under Darius but that was because Darius had not been subjected to a “royal education”.

ATHENIAN: [Cyrus] had possessions of cattle and sheep, and many herds of men and other animals, but he did not consider that those to whom he was about to make them over were not trained in his own calling, which was Persian; for the Persians are shepherds−−sons of a rugged land, which is a stern mother, and well fitted to produce a sturdy race able to live in the open air and go without sleep, and also to fight, if fighting is required …. [Cyrus] did not observe that his sons were trained differently; through the so−called blessing of being royal they were educated in the Median fashion by women and eunuchs, which led to their becoming such as people do become when they are brought up unreproved. And so, after the death of Cyrus, his sons, in the fulness of luxury and licence, took the kingdom, and first one slew the other because he could not endure a rival; and, afterwards, the slayer himself, mad with wine and brutality, lost his kingdom through the Medes and the Eunuch, as they called him, who despised the folly of Cambyses.

CLEINIAS: So runs the tale, and such probably were the facts.

ATHENIAN: Yes; and the tradition says, that the empire came back to the Persians, through Darius and the seven chiefs.

CLEINIAS: True.

ATHENIAN: Let us note the rest of the story. Observe, that Darius was not the son of a king, and had not received a luxurious education. . . . he made laws upon the principle of introducing universal equality in the order of the state, and he embodied in his laws the settlement of the tribute which Cyrus promised,−−thus creating a feeling of friendship and community among all the Persians, and attaching the people to him with money and gifts. Hence his armies cheerfully acquired for him countries as large as those which Cyrus had left behind him. Darius was succeeded by his son Xerxes; and he again was brought up in the royal and luxurious fashion. Might we not most justly say: ‘O Darius, how came you to bring up Xerxes in the same way in which Cyrus brought up Cambyses, and not to see his fatal mistake?’ For Xerxes, being the creation of the same education, met with much the same fortune as Cambyses; and from that time until now there has never been a really great king among the Persians, although they are all called Great. And their degeneracy is not to be attributed to chance, as I maintain; the reason is rather the evil life which is generally led by the sons of very rich and royal persons; for never will boy or man, young or old, excel in virtue, who has been thus educated.

If that story of an ideal warrior king (and former shepherd) having the misfortune to see less worthy sons engage in bloody strife sounds familiar, it might be because you are aware of the story of King David — a narrative that another scholar, John Van Seters, believes owes much of its detail to the history of the Persian court. One might further wonder if we can focus that provenance a little more sharply by suggesting it was the Persian court as interpreted through Hellenistic ideals.

If Plato could imagine the Persian monarchy as a kind of antithetical ideal foil to Athens, a monarchical ideal that granted liberty to former captives, and one whose kings had the self-assurance to encourage discourse with their subject people, one might conclude that nothing would have been more natural than for Hellenistic authors to find a respectful place for Cyrus and at least a few subsequent (not quite so perfect) Persian monarchs who represented “the highest form” of the alternative to the government of Athens.

Plato. “Laws.” Translated by Benjamin Jowett. The Internet Classics Archive. Accessed May 18, 2024. http://classics.mit.edu//Plato/laws.3.iii.html.

Spek, R.J. van der. “Cyrus the Great, Exiles and Foreign Gods.” In Extraction & Control: Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stolper: 68, edited by Charles E. Jones, Christopher Woods, Michael Kozuh, and Wouter F. M. Henkelman, 233–64. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2014.

Wajdenbaum, Philippe. Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. London ; Oakville: Equinox, 2011.