A most fascinating read is Lewis Dartnell’s Origins: How Earth’s History Shaped Human History.

A most fascinating read is Lewis Dartnell’s Origins: How Earth’s History Shaped Human History.

In his first chapter, he provides an answer to the question: What was it about our environment that selected for the emergence of us, bipedal, somewhat more intelligent than other primates, highly social, etc? More specifically, what was it about the Rift Valley in East Africa that made it the setting for the appearance of our first ancestors?

The first puzzle is why the Rift Valley at all and why that region does not share the dominance of rain forests that are the feature of the other regions in the same latitudes — Amazon, South-East Asia.

Dartnell brings together the wealth of published research into questions like these and identifies the following factors:

1. The crashing of India into Eurasia forcing up the Himalayas. To be more specific, it is the subsequent erosion of the Himalayas — the effects of ice sheets and rain — that has led damp soil to pull carbon dioxide out from the atmosphere, react with it and form calcite that is washed away down to the oceans where it is transformed into shells by sea creatures. Carbon dioxide extraction from the atmosphere has had a cooling effect on the globe. The cooling has resulted in less rainfall and a drier climate.

2. At the same time, and related to the above, moisture is being sucked into the Himalayan and Tibetan region to create the monsoon system over India and South East Asia, but this has meant the pulling of moisture from East Africa.

3. The crashing of Australia into New Guinea led to land rises that blocked off the warm waters that had flowed from the Pacific into the Indian Ocean, allowing colder waters from the North Pacific to take their place.

4. Add 1, 2 and 3 above and we begin to see why rain forests are not to be expected in East Africa.

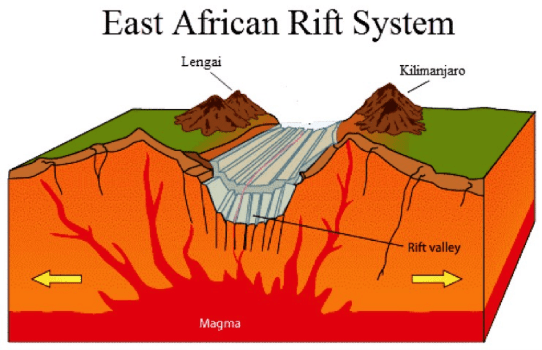

Next scene: tectonic shifts around East Africa

5. Magma pushed up along the region from the Red Sea through to Kenya and beyond. That caused the overlying crust to slowly split, making huge cliffs either side of a new valley floor that was some half a mile above sea level.

6. The mountains forming on the east side blocked rainfall from the Indian ocean from reaching much of the valley itself. Add that to #4 above.

7.

And the formation of the Rift changed not only the climate but also the landscape, in the process transforming the ecosystems of the area. East Africa was remoulded from a uniform, flat area smothered in tropical forest, to a rugged, mountainous region with plateaus and deep valleys, its vegetation ranging from cloud forest to savannah to desert scrub.

Although the great rift started to form around 30 million years ago, much of the uplift and aridification happened over the past 3-4 million years. Over this time, the same period that saw our evolution, the scenery of East Africa shifted from the set of Tarzan to that of The Lion King. It was this long-term drying out of East Africa, reducing and fragmenting the forest habitat and replacing it with savannah, that was one of the major factors that drove the divergence of hominins from tree-dwelling apes. The spread of dry grasslands also supported a proliferation of large herbivorous mammals, ungulate species like antelope and zebra that humans would come to hunt.

But it wasn’t the only factor. Through its tectonic formation the Rift Valley became a very complex environment, with a variety of different locales in close proximity: woods and grasslands, ridges, steep escarpments, hills, plateaus and plains, valleys, and deep freshwater lakes on the floor of the Rift. This has been described as a mosaic environment, offering hominins a diversity of food sources, resources and opportunities.

The widening of the Rift and the upwelling of magma was accompanied by strings of violent volcanoes spewing pumice and ash across the whole region. The East African Rift is dotted with volcanoes along its length, many of which formed in just the last few million years. Most of these lie within the Rift Valley itself, but some of the largest and oldest are growing on the edges, including Mt Kenya, Mt Elgon, and Mt Kilimanjaro, the tallest mountain in Africa.

The frequent volcanic eruptions spilled lava flows that solidified into rocky ridges cutting across the landscape. These could be traversed by nimble-footed hominins, and along with the steep scarp walls within the Rift may have provided effective natural obstacles and barriers for the animals they hunted. Early hunters were better able to predict and control the movements of their prey, constraining escape routes and directing them into a trap for the kill. These same features may also have offered vulnerable early humans a degree of protection and security from their own predators that prowled the landscape. It seems that this rough and varied terrain provided hominins with the ideal environment in which to thrive. Early humans, who, like us, were relatively feeble and did not have the speed of a cheetah or the strength of a lion, learned to work together and take advantage of the lie of the land, with all its tectonic and volcanic complexity, to help them hunt. (pp. 11-12)

8. That wasn’t all. There were faster changes that favoured adaptable intelligence. There was significant variation in climate between the upper peaks and the lower valley regions of the Rift Valley. The former saw rainfall that flowed into lakes below; the below region was much hotter and subject to high rates of evaporation. Very small changes in climate have had major effects on the water levels below. Rhythmical shifts in the earth’s orbit around the sun (Milankovitch cycles) result in changes to the amount of sunlight in winter and summer seasons, resulting in the formation of lakes and somewhat regular water supplies in the Rift Valley, but also resulting in extremely variable climate in the region, and in the instability of water supplies in other parts of the Valley. Lakes would come and go. Very wet periods would alternate with very arid conditions. We are looking at variable phases every 800,000 years approx — super fast in geological and evolutionary terms.

The timing of when new hominim species emerged — often associated with an increase in brain size — or fell extinct again, tends to coincide with these periods of fluctuating wet-dry conditions. . . . What’s more, the development and spread of the different stages of tool technologies . . . — Oldowan, Acheulean, Mousterian — also correspond with the eccentricity periods of extreme climate variability. (p. 22)

All in all . . .

All in all, the human animal was forged by a peculiar combination of planetary processes all coming together in East Africa over the past few million years. It wasn’t just that the region had dried out as Earth’s crust bulged with the magma plume rising beneath, shifting from the relatively flat, forested habitat of our primate ancestors into arid savannah. The entire landscape had become transformed into a rugged terrain cut through with steep fault scarps and ridges of solidified volcanic lava: this was a world fragmented into a complex mosaic of different habitats that continued to change with time. In particular, the extensional tectonics of East Africa ripped open the Rift Valley to create a particular geography of tall walls collecting rainfall and a hot valley floor. Cosmic cycles in Earth’s orbit and spin axis periodically filled basins on the rift floor with amplifier lakes that responded rapidly to even modest climate fluctuations to create a powerful evolutionary pressure on all life in this region.

These unique circumstances of our hominin homelands drove the development of adaptable and versatile species. Our ancestors came to rely more and more on their intelligence and on working together in social groups. This diverse landscape, varying greatly across both space and time, was the cradle of hominin evolution, and out of it emerged a naked and chatty ape smart enough to come to understand its own origins. The hallmarks of Homo sapiens – our intelligence, language, tool use, social learning and cooperative behaviour; which would allow us to develop agriculture, live in cities and build civilisations – are consequences of this extreme climatic variability, itself produced by the special circumstances of the Rift Valley. Like all species, we are a product of our environment. We are a species of apes born of the climate change and tectonics within East Africa. (pp. 24-25)

Sometimes I find myself expressing some frustration with the rapidity of so many changes happening all around me. I suppose when I look at it all in the grand scheme of things I should see that frustration as the impetus that has made us what we are.

The more I learn about all the variables that have gone into allowing life to evolve in the first place and for us to have been one of its byproducts the harder I find it to imagine others like us elsewhere in the universe. But you may differ on that one.

Dartnell, Lewis. 2018. Origins: How the Earth Made Us. New York: Basic Books.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Someone wins the lottery, no matter how stupendous the odds seem.