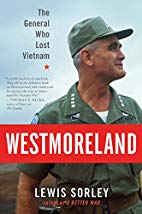

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book, Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. (You can find the video at the end of this post.)

A few weeks ago, I was dealing with a mold issue in our RV’s bathroom. (Note: If you see mushrooms growing out of a crack in the wall, it’s usually a bad sign.) Having resigned myself to working with gloves, wearing a mask, sitting uncomfortably on the floor for at least an hour, I resolved to find a long audio program on YouTube and let it play while I worked. I happened upon a presentation by Dr. Lewis Sorley, based mainly on his book, Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. (You can find the video at the end of this post.)

I had studied the Vietnam War as an undergraduate history major back in the 1980s, so much of what Sorley had to say covered old ground for me. Back in those days, of course, we could still refer to it as America’s Longest War without worrying whether some other disastrous Asian war might overtake it. After all, we had “learned the lessons of Vietnam,” right?

Later, as a student at Squadron Officer School, I certainly thought we had learned those lessons. From a policy perspective, the first lesson had to be clarity of purpose. On the military side, we would never again fight a limited war of attrition; instead, we would use overwhelming force to achieve clear objectives. In a nutshell, this is the “Get-In-and-Get-Out” Doctrine: Know your objectives. Achieve them in minimum time with minimal loss of life.

We would absolutely avoid any future quagmires. Or so we thought.

I should mention that several other lessons — both spoken and unspoken — arose out of the Vietnam experience. The practice of embedding journalists within fighting units came out of the beliefs that the press should not have been permitted to work as independent observers and that allowing them to move freely in South Vietnam had been a mistake.

An expanding set of myths about why we lost the war blossomed quickly into an alternate history in which unreliable draftees, fickle politicians in Washington, pinko journalists, and the hippy peace movement conspired to keep us from winning.

Some of these myths took hold naturally, as veterans told their personal stories, relating with frustration how the body counts didn’t seem to matter, that the V.C. would return again and again, that the stupid war of attrition didn’t work, and what’s more, nobody seemed to give a damn that it wasn’t working. That much was true.

But much of the alternate history which is embedded in the American psyche has its roots in the response by the military-industrial complex (MIC) to a disaster that posed an existential threat to the elite power structure in the United States. On the one hand, it seems audacious for the military to presume to explain what went wrong and what we needed to do in the future. After all, the Pentagon Papers were public knowledge. Had they forgotten that unfortunate fact? On the other hand, what else could they do?

The first item on the agenda was to rehabilitate the American fighting man. Inside the Pentagon and within the MIC as a whole, they welcomed the end of the draft. One cannot maintain an empire with conscripts. What they needed were well-trained, professional warriors from a particular class, staunchly loyal to the nation. A cross-section of citizens from different walks of life — the citizen army that helped win World War II, for example — is not what you want when you’re putting down an indigenous revolt against United Fruit.

That said, the glorification of the troops played an important role in the overall rehabilitation of the military’s image. Looking back, we citizens needed to see the returning soldiers, marines, and airmen as victims of the antiwar movement. They had been jeered, assaulted, and spat upon. (See “The Myth of the Spitting Antiwar Protestor” (NYT)) These images became ingrained in our minds. The point was not to victimize the vets, but to instill a sense of shared shame among the citizenry and to encourage us to resolve never again to question the motives or actions of “our boys.”

Here is the origin of the “support the troops” movement. Ultimately, the MIC cares little about your love of the troops. What it wants is unimpeded freedom of action. If they can make you see every war as a holy war and every soldier as a hero, then you will be less likely to ask uncomfortable questions.

The second rehabilitation was that of the war itself. The United States decided in 1950 to turn its back on decolonization and instead support the return of France to Indochina. We knew what we were doing. It was a deliberate act.

When Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the independence of Vietnam from French rule on September 2, 1945, he borrowed liberally from Thomas Jefferson, opening with the words “We hold these truths to be self-evident. That all men are created equal.” During celebrations in Hanoi later in the day, sleek U.S. fighter planes swooped down over the city, U.S. Army officers stood near the reviewing stand, and a Vietnamese band played the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Toward the end of the festivities, Vo Nguyen Giap spoke warmly of Vietnam’s “particularly intimate relations” with the United States—something, he noted, “which it is a pleasant duty to dwell upon.”

The prominent role played by Americans at the birth of Vietnam appears in retrospect one of history’s most bitter ironies. Despite the glowing professions of friendship on September 2, the United States in 1945 acquiesced in the return of France to Vietnam and from 1950 to 1954 actively supported its efforts to suppress Ho’s revolution, the first phase of a quarter-century American struggle to control the destiny of Vietnam. (Herring 2013, p. 3, bolding and formatting mine)

In the years following, we engaged in illegal wars in Cambodia and Laos, helped assassinate South Vietnam’s president, and pursued a brutal policy of rural pacification.

Yet, after a suitable period of forgetfulness, a new perspective on the war emerged. Now we would say along with Ronald Reagan, “It’s time that we recognized that ours was in truth a noble cause.”

And we would say this with a straight face.

None of what I’ve written so far should surprise anyone who has studied the war and its aftermath. But something Lewis Sorley said in his talk struck me. I realized in an instant how I had been manipulated along with everyone else. Such is the power of really well-crafted propaganda.

The image I have in my mind of the LBJ war years is that of President Johnson standing over maps of North Vietnam, calling out and marking the precise coordinates of each bomb to be dropped. It’s the image that coincides with the lesson we military officers and historians had learned through hard study and cruel experience, namely that once the military executes the plan, the civil authority needs to stand back. We didn’t do that in Vietnam, and total disaster followed.

But my memory had been clouded by a well-crafted myth. Here’s how Sorley put it in his book on General Westmoreland:

The conventional view of the war, even now, is that it was micromanaged from Washington. There are many stories of how, at Lyndon Johnson’s White House “Tuesday Lunches,” he and other top (mostly civilian) officials would even select and approve individual bombing targets in North Vietnam and make other such detailed determinations about aspects of the war. But those decisions had to do with actions taken outside South Vietnam. Within South Vietnam, the U.S. commander had very wide latitude in deciding how to fight the war. This was true for Westmoreland, and equally true for his eventual successor. (Sorley 2011 p. 73, bold emphasis mine)

If anything, LBJ was guilty of not stepping in and providing the oversight that his role as commander in chief demanded. Westmoreland’s continual blunders and his inability to adapt to the situation on the ground and learn from his past errors should have alerted the civil authority that the quagmire would never end so long as Westy was in charge.

At least in the views of some observers, responsibility for such failure resided more with LBJ than with his field general. “No capable war President,” wrote historian Russell Weigley, “would have allowed an officer of such limited capacities as General William C. Westmoreland to head Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, for so long.” (Sorley 2011, p. 205, bold emphasis mine)

Once again, if you have studied the war, none of this should be news to you. Nor should it have been a surprise to me. Yet, one of my strongest memories of the war is the image of LBJ apparently micromanaging the entire war. That mental image, which still persists, is false.

As I said, images like these, which have burned into our psyches have colored the ways in which we understand the world. Moreover, the lessons we think we have learned from them affect our beliefs and our resulting behavior.

In the light of Westmoreland’s “very wide latitude,” I think we need to acknowledge what really happened in Vietnam. The U.S. military had free rein in the South. Recall that this is where the war was fought. The failures of military leadership in theater combined with equally poor civilian and military leadership in Washington brought us to disaster.

We need to be aware of false histories and misleading images, along with the bad lessons and harmful solutions smuggled in with them.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6LR-UJsYRc]

Bibliography

Herring, George C.; America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975, McGraw-Hill Education (2013)

Sorley, Lewis; Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam, Mariner Books (2012)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The Ministry of Truth is much slower in the real world than in the book.

OP: “nobody seemed to give a damn that it wasn’t working”

Robert McNamara cared, in the sense that he requested higher V.C. body counts. He was applying his World War II experience with the “Office of Statistical Control” per analysis of U.S. B-29 bomber’s efficiency and effectiveness and his subsequent recommendations for getting the maximum number of dead Japanese for each B-29 lost. See: USAAF’s emphasis on firebombing during the campaign against Japan.

As I understand there is a relationship between between the continuously higher V.C. body counts requested by McNamara and the American’s KIA rate of new O-1 officers (butter-bars).

However McNamara’s stated first goal was to avoid a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union, so he was constrained in some ways.

Thank you for this. Sorting out the truth is arduous at best. the liars count on us losing interest after a very short period … and they are not wrong.