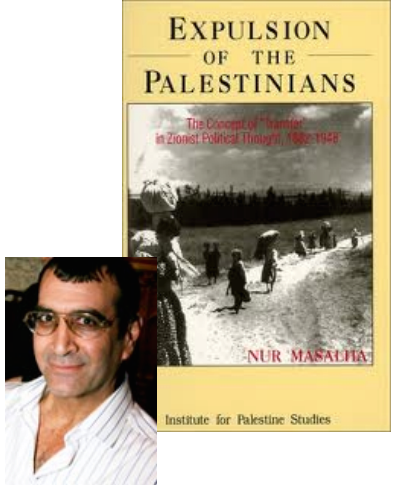

This series of posts has put a spotlight on the historical evidence that despite certain public comments to the contrary the pre-1948 Zionist movement was dominated by the intention to cleanse Palestine of its Arab population to make way for the settlement of Jews from Europe and elsewhere. Much of the evidence surveyed has come from archival sources such as the Israel State Archives and the Central Zioist Archives (CZA), as well as from personal diaries of key Zionist leaders and minutes of Zionist meetings. This is the eleventh post of what are my notes from Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948 by Nur Masalha.

This series of posts has put a spotlight on the historical evidence that despite certain public comments to the contrary the pre-1948 Zionist movement was dominated by the intention to cleanse Palestine of its Arab population to make way for the settlement of Jews from Europe and elsewhere. Much of the evidence surveyed has come from archival sources such as the Israel State Archives and the Central Zioist Archives (CZA), as well as from personal diaries of key Zionist leaders and minutes of Zionist meetings. This is the eleventh post of what are my notes from Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948 by Nur Masalha.

This post begins with a look at one more transfer plan that interested many Zionists even though it failed in the end to be implemented:

Edward Norman’s Plan of Transfer to Iraq, 1934-48

Edward Norman (1900-1955) was an American Jewish millionaire deeply involved in fund-raising for the Jewish settlement in pre-1948 Palestine, the Yishuv. With the collaboration of Yishuv and other major Zionist leaders he spent much time and energy working on a transfer plan throughout the years 1934 to 1948.

Norman’s first plan, 1934, was titled An Approach to the Arab Question in Palestine. The premise of this 19 page memorandum:

immigration and possession of the land by definition are the basis of the reconstruction of the Jewish homeland.

Norman understood that Jewish colonization was “a general cause of concern” for the Palestinian Arabs because it entailed

taking over Palestine without the consent of the indigenous population.

The crux of the problem for the Yishuv, therefore, in Norman’s view, was that Jews were to gradually take over Palestine while simultaneously finding a new place for the Arab population to live.

The solution, he suggested, was “the kingdom of Iraq”. What he wanted was for the Iraqi government to agree to donate agricultural land for the Palestinian Arabs and to facilitate their free transfer, along with all their cattle and other property. The Arab press would have to support the plan, too.

What is interesting here is Norman’s assumptions about the character of Arabs: no matter how long they had been settled agriculturalists they were still nomads at heart —

It must be remembered that a transportation such as suggested by Arabs from Palestine to Iraq would not be a removal to a foreign country. To the usual Arab there is no difference between Palestine, Iraq, or any other part of the Arab world. The boundaries that have been instituted since the War are scarcely known to many of the Arabs. The language, customs, and religion are the same. It is true that a moving of any kind involves leaving familiar scenes, but it is not a tradition of the Arabs to be strongly attached to a locality. Their nomadic habits still have that much influence, even among the settled elements. (Masalha, p. 143)

Norman feared that anything other than economic inducements for the Palestinian Arabs to evacuate their homes would backfire in the long run. He wanted to avoid a situation where the Jewish settlers looked as though they were pressuring the Arabs to leave:

If the Jews ever succeed in acquiring a major part of Palestine a large number of Arabs perforce will have to leave the country and find homes elsewhere, if they are forced out inexorably as the result of Jewish pressure they will go with ill-will and probably will cherish an enmity towards the Jews that might persist for generations and that would render the position of the Jewish homeland precarious. The rest of the world, too, easily might come to sympathize with the Arabs. (p. 143)

How to initiate the plan

The first step was to involve influential and sympathetic Jewish persons and to make very discreet investigations into Iraq’s willingness to assist. The costs of moving Arabs village by village to Iraq would have to be ascertained without raising any public alarms. The necessary meetings with the British Colonial Office were also mapped out. The first Arabs to be moved would be the ones along the Palestinian coast since their agricultural ways were the more easily transferable to Iraq in the initial stages.

Revision 1

In 1937, however, violent confrontations between the Yishuv and Palestinians led Norman to expand and revise his plan. He had to acknowledge an unsavory fact:

In this version he elaborated on the underlying assumptions of his scheme, noting, with considerable detail, that the Zionist leadership’s public claim that the Yishuv had no “intention of dominating the Arabs” was hypocritical, and that “the Arab fears of becoming a minority are well-founded.”

Taking into account these factors as well as the futility of expecting peace and cooperation between the two groups, Norman concluded:

“If the Jews must have Palestine, but cannot have it while more than 800,000 Arabs live there, the Arabs must be induced to give it up and a considerable proportion of them to move elsewhere,” possibly to the “Shatt-el-Gharraf” area of Iraq. . . .

(p. 145, my formatting)

Why not move them just across the river to Jordan?

He ruled out Transjordan because it was “not conceded by the Jews as being permanently outside their colonizing area, and in view of the number of Jews requiring emigration from Europe they can be expected to need it, and therefore it would be wasteful and unintelligent to think of settling the Palestine Arabs in Transjordan.’

How to initiate the revised plan

Costs were worked out in detail. The resettlement of a family of six to Iraq was $1800, a modest amount since, Norman noted, “Arab peasants are accustomed to very simple houses.”

Where was the money to come from? From the sale of Arab lands in Palestine to the Jews.

Norman’s propaganda persuasion plan appears to me to be remarkably similar to the methods used by the ancient imperial powers to transfer whole populations, including the Jews. See, for example, the origins of biblical Israel post in which I outline the evidence that Babylon and Persia used similar myth-making to facilitate the mass transfer of populations.

How to persuade the Arabs?

“[A] very careful and expertly managed educational campaign” could be launched among the Palestinians to facilitate the move, emphasizing the advantages of Iraq’s “Shatt-el-Gharraf” region compared to the “difficult soil” of Palestine, and “of living in the independent Arab kingdom that once saw the highest point of Arab glory,” compared to Palestine under British rule with the number and power of the Zionists on the rise. Norman added:

Perhaps a widespread desire to go to Iraq as their true national home could be inculcated among the Palestine Arabs, similar to the emotional desire among the Jews of Eastern Europe to dwell in Palestine as their national home.

(p. 146)

Next stage

Details of contacts and methods were set out for the raising of the money needed to pay for the plan. At the same time plans for

sending experts to Iraq “very quietly and unostentatiously” to check into the country’s agricultural and irrigation possibilities, and investigating “the situation in Palestine with regard to land holdings among the Arabs and the values thereof, and to make preliminary inquiries as to transportation costs and other portable expenses”

were developed. It was important that at this stage the Iraqi government be kept in the dark about the transfer plan for fear of alarming the Palestinian Arabs and prematurely sparking protests against it before it could begin.

Gaining the support of the British and Iraqi governments was essential. To the former, it would be argued that a Jewish population in Palestine would be a strategic asset to Britain given the context of Arab independence movements in the Middle East; to the latter, promises of enormous economic development with the settlement of new populations and the irrigation of whole new areas would be made.

How to initiate

Discretion was of utmost importance. One could not just walk up to the Iraqi government heads and say one wanted them to take in all of the Palestinian Arabs so the Jews could settle in Palestine. But how could the planners acquire the detailed information they needed to work out the specifics of the transfer plan and gradually win Iraqi support?

Warburg [a New York banker active in Yishuv institutions] encouraged me [Edward Norman] to go to England and find someone who would be capable of obtaining the information still needed, it was assumed that l could not obtain the information by going to Iraq myself, since under the prevailing conditions in the Near East, the motives of any Jews would be suspect, and instead of obtaining information he probably only would arouse antagonism. Therefore, it was essential to send a man who was not a Jew and who at the same time would be “person grata” to the lraqians [sic].

(p. 148, citing a 1938 Norman report kept in the CZA and a 1937 letter to the British Colonial Office housed in London’s Public Record Office. My emphasis)

One of the several notable Zionist leaders Norman met in London in December, 1937, was Jabotinsky. Norman wrote in his diary:

He (Jabotinsky) has already read a copy of my memorandum on lraq…. He is very much in favor of the idea. He said, however, that it will be very difficult to move the Arabs to leave the Land of lsrael…. Jabotinsky raised an original idea according to which, if the plan will reach a point at which Iraq would be willing to collaborate and issue an invitation for the Palestinian Arabs to immigrate to it, the ‘World Zionist Organization would be clever if it pronounced itself publicly to be against Arab immigration, then the Arabs will be certain that the plan is not originally Jewish, and that the Jews want them to stay in the country in order to exploit them, so they will be very eager to go to Iraq. There is a very Machiavellian nature to this, but this could be a healthy policy towards suspicious and ignorant Arab public. Jabotinsky said that if his Revisionist New Zionist Organization will issue an announcement at the right moment against Arab transfer from the Land of Israel, this will create a very great impact on the Arabs to the extent of creating the opposite, and they will get out.

(p. 149. This record has been used to argue that Zionists such as Jabotinsky had the “higher moral authority” since they only wanted a voluntary transfer of Arabs, but Masalha argues that such an interpretation contradicts his insistence elsewhere on an “iron wall of bayonets”.)

Enter the British press

The “man who was not a Jew and who was at the same time . . . person grata to the Iraqians” that Norman decided to send was the former editor-in-chief of the British weekly Great Britain and the East, H.T. Monague Bell. Bell was hosted by the Iraqi king, prime minister and cabinet as a guest who was keenly interested in the economic development of newly independent kingdom of Iraq and who was keen to alert the wider world to Iraq’s interests. For his proposed articles Bell asked questions that led Iraqis to see for themselves the need for large-scale immigration. Bell remained careful not to suggest that this immigration need be met by Palestinian Arabs; the Iraqis had to believe that that notion came to them from among themselves. Bell continued to work with Iraqis in this capacity as an influencer of political opinion until the 1940s, in the pay of Norman and then the World Zionist Organization.

British politicians were also influenced by Bell’s published articles and some concluded “for themselves” (as Bell intended) that the Palestinian problem and the problem of Iraq’s development could both be solved by transferring Palestinians to Iraq.

Support from The Big Three

The three most important leaders of the Jewish Agency were Weizmann, Ben-Gurion and Shertok. When Norman met all three in 1938 they all expressed a strong willingness to cooperate with his transfer plan to Iraq, and were especially keen to see the idea appear to come from the Iraqis themselves, not from the Zionists. I gloss over the details of these meetings except to quote one sentence written by Weizmann to Norman:

“l need not tell you that I shall do what l can to support your efforts, for which I have the highest admiration.” (p. 153)

Extract from Lowdermilk’s Palestine, Land of Promise:

What of the million and a third Arabs in Palestine and Transjordan? . . . [T]hey could easily settle in the great alluvial plain of the Tigris and Euphrates Valley, where there is land enough for vast numbers of immigrants. The soil of Iraq is so fertile and irrigation waters are so abundant in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that the land needs more farmers. . . Centuries of neglect of their lands and consequent wastage demonstrate that the Arabs have not shown the genius or ability to restore the Holy Lands to their possibilities. But the Jews, by their magnificent examples in colonization, have demonstrated their ability . . . . (pp. 127f)

Up to and throughout World War II Norman worked to solicit top level American support for the plan and during the war was joined by Weizmann. They argued that the Allied war effort would be greatly supported by the transfer of Palestinian agricultural labour to Iraq so as not to rely upon food from other non-Middle Eastern sources. Norman explained:

“No doubt intelligent and careful propaganda methods would have to be used. Perhaps at first people would be asked to go to Iraq merely as paid agricultural laborers,” later “to become permanent settlers.”

An American Christian Zionist and soil expert, Walter Clay Lowdermilk, appears to have supported Norman. Lowdermilk had visited Iraq in connection with dam engineering and subsequently published Palestine, Land of Promise, in which he spoke in support of the for the transfer of Palestinian Arabs to Iraq.

Britain rejects of the plan

The British Colonial Office and Foreign Office on the other hand flatly rejected Bell’s efforts, describing his transfer ideas as “amateurish and impractical”.

[I]t could not possibly succeed, he wrote, since there was not the slightest reason to assume that the Palestinian Arabs would accept a voluntary transfer or that the Iraqi government, with its known pan-Arab sentiments, would ask for their evacuation to Iraq.83

83. Memorandum dated 26 February 1941, in CO 733/444/ 75906. Two years later, in April 1943, a Christian Palestinian Arab named Francis Kettaneh submitted a memorandum to the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, in which he protested that Norman had “widely distributed a memorandum in which he urges that the United Nations forcibly expatriate and transplant all Arabs, whether Muslim or Christian, out of Palestine and settle them in Iraq. This action is urged so as to make place immediately for one million Jews who could immediately immigrate into the country.” PRO, FO 371/35034, E 2686/87/31.

(pp. 154, 171-72)

Continued hopes for American support

Edward Norman appealed directly to President Truman explaining that the problems of Jewish settlement in Palestine could be solved overnight with the transfer of the Palestinians to Iraq. More support could come from Britain if Norman’s own studies demonstrating that the details of Palestinian settlement in Iraq had all been worked out were made better known.

Several years ago I made a thorough study of the capacity of Iraq to absorb a large proportion of the Palestinian Arabs. My findings, which are based on generally-accepted facts, indicate that in every way the resettling of some 750,000 Palestinian Arab peasants in Iraq involved no practical (as distinguished from political) difficulties.

Norman proposed to turn over to the president the “detailed facts and figures” and “supporting authoritative data” that he had collected. This he did in a memorandum dated 1 November 1945.

(p. 154, citing letter of 4 October 1945 by Norman)

Failure of the plan, but…

Masalha concludes his discussion of Norman’s plan with the following:

Norman’s “voluntary” transfer scheme to Iraq came to nothing, it is interesting to note, however, that during the Palestinian refugee exodus of 1948, members of the Israeli government Transfer Committee . . . insisted on obtaining “Norman’s treasures” – transfer memoranda and related materials he had been writing and collecting over the last fourteen years – both through Jewish Agency and Foreign Ministry channels. Norman agreed, but demanded “that a personal letter be sent to him by Mr. Shertok (and by Mr. Shertok only), expressing recognition for all he has done in this particular field and for his putting at the disposal of the Israeli Government the result of his earlier activities.”

(pp. 154f)

.

Continuing…

.

Masalha, N. (1992). Expulsion of the Palestinians: the concept of “transfer” in Zionist political thought, 1882-1948. Washington, D.C: Institute for Palestine Studies.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Implementation of bronze-age mythology in the 2oth century has led to nothing but permanent hostility and frequent wars. It should be a warning if people could drop their need for imaginary friends.

Especially in those days, God and religion provide the moral justification for the out-group hatred, not the other way around. Having been to a place where this isn’t really an out-group to hate, it seems that religion is a veneer over nothing, in other words, art for people who don’t do art.

Shall we look forward to an 11 + part article on the expulsion of the Jews? Just kidding. Sigh.