….. In surveying references to angels during this time, one of the most common features in the names of angels is the appearance of the element of ‘el’.53 This survey reveals that the most common angelic characters of this period were named Michael, Gabriel, Sariel/Uriel, and Raphael.54 In other words, a prosopographical analysis of the names of the particular angels known to Jews in the Second Temple period shows that the name Jesus does not conform to the way angelic beings were designated as such. Because the name Jesus is never associated with an angelic figure, nor does the name conform to tropes of celestial beings within Judaism, Carrier’s assertions are unconvincing.55

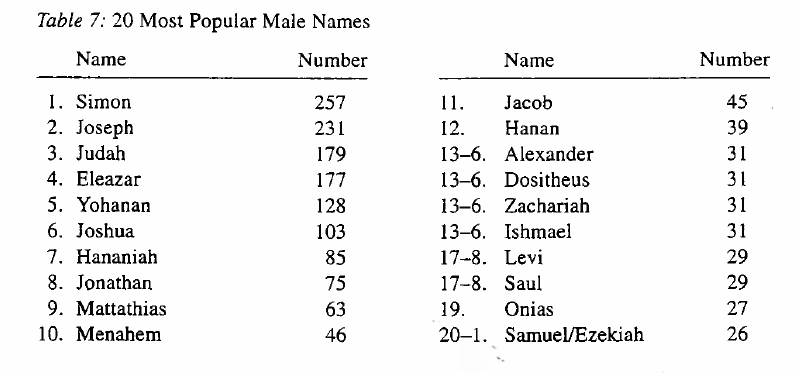

Furthermore, studies of Second Temple names found in Jewish texts, ossuaries, and inscriptions only associate the name Jesus with human figures. The name Jesus was so common and widespread it was one of the six most popular names for Jewish males.56 This commonality is particularly on display when Josephus distinguishes between the different Jesus figures of the period, such as Jesus, son of Gamaliel, who served as high priest during the Maccabean period, as well as Jesus, son of Daminos, who served as high priest in 62-63 ce, only to be succeeded by Jesus, son of Sapphias, who served from 64-65 ce. Similarly, within early Christian literature, Jesus’ name and the power associated with it is presented as Jesus the Christ (Ιησούς Χριστός)’, likewise distinguishing him from the other Jesus figures of the time.57 Carrier’s argument does not adequately explain why an angelic figure would have a name so commonly associated with human beings, let alone one which does not conform to typical angelic naming conventions. At no point does an angel or celestial being called Jesus appear within Second Temple Judaism, and Jesus’ exhibits all the signs of a mundane name given to a human Jewish male within the period.

Gullotta, D. N. (2017). On Richard Carrier’s Doubts. Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus, 15(2–3), 310–346. https://doi.org/10.1163/17455197-0150200 pp. 326-328

That sounds like a reason to be very cautious about accepting a hypothesis that a divinity would be named Jesus but it is also a double sided coin. The fact is that Jews did accept the name Jesus for a divinity or supernaturally exalted being worthy of worship. We know early Christians were quite capable of assigning a new name to a person to indicate a significant change of role or status. What if the historical Jesus had been named Simon (the most common male Jewish name of the time) or Joseph or John? How likely are they to have felt comfortable singing the praises of Dear John or Joe, John Christ, Simon Christ? If we imagine that living with even more common names than Jesus identifying their heavenly Christ then what are we to make of them sticking with Jesus even though that was one of the top half dozen most ordinary names known?

Sometimes a discipline can benefit from injection of new ideas from another field of study and I think a way out of the above conundrum is to be found in a 2011 Histos article by the classicist John Moles, Jesus the Healer in the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and Early Christianity.

I have discussed Moles’ article before at

and

The full text of the 66 page article is available at the above link to the title Jesus the Healer.

The classicist was not a mythicist, but in the abstract to his article he did talk about the mutual benefits of closer interdisciplinary efforts between the Classics and Biblical Studies departments:

Abstract. This paper argues that the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles contain sustained and substantial punning on the name of ‘Jesus’ as ‘healer’ and explores the implications for the following: the interpretation and appreciation of these texts, including the question of whether (if at all) they function as Classical texts and the consequences of an affirmative (however qualified): present-day Classicists should be able to ‘speak to them’ and they in turn should ‘respond’ to such Classical addresses, to the benefit not only of New Testament scholarship but also of Classicists, who at a stroke acquire five major new texts; the constituent traditions of these texts; the formation, teaching, mission, theology, and political ideology of the early Jesus movement, and its participation in a wider, public, partly textual, and political debate about the claims of Christianity; and the healing element of the historical Jesus’ ministry.

I won’t repeat the detail I covered in my earlier posts but will mention just a few items that hopefully will encourage interested readers to consult the originals. Moles points out the importance of puns in this context:

Much scholarship over the last four decades has demonstrated the importance of puns and name puns in Classical societies, cultures and literatures, including historiography and biography. (p. 125)

Moles discusses in some detail the significance and role of the god and hero Jason in Hellenistic Greek culture. Jason was a healer and a type of dying and rising (through the mouth of a serpent) god. Jesus is the Jewish equivalent the name Jason:

The Palestinian Jewish Jesus bore the very popular name ישוע (‘Joshua’), which means something like ‘Yahweh [or ‘Yah’—shortened form] saves’.45 The Jewish-Greek form of the name, found in the NT, is ‘Ιησούς, whence our ‘Jesus’. Bilingual and etymological puns on the meaning of ‘Joshua’/’Ιησούς as ‘Yahweh saves’, alike in the Gospels and Acts (as we shall see), and in the letters of Paul and of others in the NT, are clear and acknowledged in some of the more linguistically alert scholarship.46 But there is a crucial additional factor: Jews who bore the name ישוע and wanted a straight Greek equivalent chose ‘Ιάσων (Ionic form Ίησων, modern ‘Jason’): an equivalence attested in official and governmental contexts.47 This Greek name actually means ‘healer’ (~ ίάομaι) and readily produces etymological puns.48 Jews who adopted Greek names generally tried to adopt ones nearest in form and meaning to the original. So not only do Ιησούς, the Greek-Jewish form of ‘Joshua’ and the name of a renowned Jewish ‘healer’, and ‘Ιάσων, the Greek form of ‘Ιησούς/’Joshua’ and a name which actually means ‘healer’, look similar and mean similar things: from a Hellenistic Jewish perspective, they are actually the same name, as any Jew with a modicum of Greek would have known.49 For us it is of course completely immaterial in this sort of context whether they are actually the same name.

There are also wider considerations. . . . (p. 127)

There is an inevitable link between the concepts of saving and healing, and Moles has much to say about the two names together. Example,

[Jason] derives from the pagan goddess of healing who is called Ίάσω (Ίήσω in Ionic) . . . Thus on the Greek side Ίάσων is a human name derived from a god’s: a theophoric name, just as on the Jewish side side ישוע is a human name derived from ‘Yahweh’. Furthermore, for the early Christians, this [Jesus] is in some sense, and to some degree, himself a divine figure. There is also a simple matter of sound. Ιησούς, Ίάσων and Ίάσω not only look very similar: they sound very similar. And the sound of names is very important. There is also a matter of extended meaning. There can be important links between ‘saving’, the basic meaning of ‘Joshua’, undeniably punned on in the NT, and ‘healing’, both at the levels of divine and qausi-divine and alike in medical, religious/social and political contexts. Given these links and the sound factor, one even wonders whether the many Greek speakers who knew that the Jewish god was denoted by ‘Yahweh’ or ‘Yah’ could also ‘hear’ both Ίη/σούς and Ίά/σων as ‘Yah saves’ directly, because -σοΰς and – σων could evoke σώζω and σώς, and whether bilingual speakers could even regard the Greek σώζω and the Hebrew verb as cognates.” (pp. 128-9)

I cannot set out all the detail here. Read the article. Except just one more, a gospel read through a classicist’s eyes:

Many Classicists nowadays, I think, would already feel that Mark’s dramatic and emphatic foregrounding of Jesus’ ‘healing ministry’ is underpinned by the very name of Jesus, which seems to be deployed both strategically (1.1, 9, 14, 17) and locally (1.24–5; 2.5, 8) in a telling way. The logic would be that the combination of Jesus’ much-repeated name, which means ‘healer’, with the lexicon of ‘tending’ and ‘cleanness’ and ‘uncleanness’ effects ‘punning by synonym’, a process further helped by the intrinsic importance attached to names (both of exorcist and demon) in exorcisms, whether Jewish or pagan. Certainly, in Mark, as in the others, use of Jesus’ name increases—sometimes dramatically—in healing contexts. By comparison with Classical texts (with which, as we have seen, Mark has some affinities), such punning would be quite elementary, naive even, by comparison with a text such as Pindar’s Fourth Pythian, which puns in subtle and allusive ways on ‘Jason’ as ‘healer’.

Back to our conundrum. . . .

Charles Guignebert — it is very probable

The following is extracted from an earlier post,

Would the historical Jesus of Nazareth really have been named Jesus of Nazareth?

We cannot say positively that [the substitution of a sacred name for his human one] did take place, but it is very probable.

It would be perfectly consistent with the process of “mythication” which the whole figure of Christ underwent, and which is already manifest in the Gospels.

Is it conceivable that the early Christians would adopt a most quotidian name for their saviour? Put bluntly like that the answer is certainly negative.

But is it conceivable that they would exalt to the highest above all others, a figure who had always and only been known as Simon, or Joseph, of John, or some other common name like Joshua (=Jesus)? That likewise seems most unlikely.

But there once was a renowned French scholar, trenchantly critical but certainly no friend of the Christ Myth advocates of his day, Charles Guignebert. He pondered our question, too, and decided that Jesus could not have been the historical “Jesus’s” real name. His followers certainly did, he believed, bestow that name on him after his death (or upon his resurrection and exaltation as they no doubt saw it).

[A]ncients in general, and the Jews in particular, attached to names, both of men and of things, a peculiar value, at once metaphysical, mystical, and magical. (Charles Guignebert (1956) Jesus, New York, University Books, pp 78f.)

Names were believed to express the special power or virtue of whatever it was they designated. Recall the potency of the name of the Jewish God.

The true name of a god, for example, whose revelation to the initiate or the believer endowed him with knowledge (gnosis), was supposed to contain, so to speak, the essence of his divine being.

We have the words of a worshiper of a pagan god beginning his prayer with: I know thy name, Heavenly One.” The Bible speaks of God naming before they were born certain persons who were destined for great things. Josephus makes the same point. The Rabbi Eliezer cited six persons who received their names before they were born:

- Isaac

- Ishmael

- Moses

- Solomon

- Josiah

- the Messiah

The name of the Jewish Jahweh was well known to be imbued with powers in magical incantations in the wider world (beyond Israel). In Israel the name was the centre of a cult. In the Pauline community the cult of the name of the Lord was substituted for that of the name of Jahweh among the Jews. Guignebert need refer to only one passage to illustrate the point, Philippians 2:9-10:

Therefore God also has highly exalted Him and given Him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those in heaven, and of those on earth, and of those in hell.

Guignebert’s comment:

In other words, the name of Jesus has a peculiar power over the whole of creation, so that the spiritual beings of the world, who rule the elements and the stars, prostrate themselves at the sound of it.

Origen further reminds us (Contra Celsum 8:58) of the power of the name of Jesus over demonic powers and spirits.

Thus warned . . .

The above references only touch on the question of the importance of names, and in particular the name of the Messiah and of Jesus, and Guignebert will elaborate on them in the coming pages. Though brief, they are nonetheless

sufficient to warn us against any purely human, obvious, and popular interpretation of the name of Jesus the Nazarene. The most reasonable and probable explanation, if we reflect for a moment, is that the original followers of Christ, those, that is, who first recognized him as Christ, the Messiah, gave him a name which set him above humanity and expressed his divine nature. (Guignebert, Jesus, p. 77)

Paul certainly understood the name of Jesus in this light. And if the later authors or redactors of the Gospels did not appear to have this view “it is perhaps because they belonged to an environment in which the meaning of the Aramaic had been lost.”

Note also that according to Paul the followers of the Lord Jesus are “those who call upon his name” — 1 Cor. 1:2.

To the author of John 1:12 those who are given the right to become children of God are those who “believe in his name.”

The Greek Ἰησοῦς

The Greek word in our Gospels and Paul “is only the transcription of the post-exilic Hebrew word, Jeshuah, which is derived from the more ancient form Jehoshua, or Joshua, the Joshua of our Bibles.” In the Greek Bible Ἰησοῦς is used for Joshua (Exodus 17:10), Jehoshua (Zechariah 3:1) and Jeshuah (Nehemiah 7:7; 8:7, 17).

The old name, after a long period of obsolescence, reappeared in its new form about 340 B.C., and became very common towards the beginning of our era. Its original, etymological meaning is “Jahweh is help,” or, “the help of Jahweh”; obviously, for a prophet, a vessel of the Holy Spirit, a name preordained. So thought, certainly, the editors of Matthew and Luke, both of whom attributed the choice of this name to the will of God, and associate it with the divine work which he who bore it was destined to accomplish. (p. 78, my emphasis)

Note the way “Matthew” introduces the name:

The angel of the Lord appeared to [Joseph] in a dream and said, “. . . . You are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins.” (Matthew 1:20-21)

In the Gospel of Matthew, then, the name is pre-ordained and its meaning (i.e. Saviour) is given special emphasis.

Compare Luke 1:30-32:

The angel said to [Mary] . . . “You will be with child and give birth to a son, and you are to give him the name Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High.”

For this author, “it is the quality of Son of God which is in some way implied by the name Jesus.”

And Emmanuel (“God is with us”)

It is to be observed that Matthew (i.23), citing in reference to Jesus the passage of Isaiah (vii.14) which prophesies the birth of a miraculous child who shall be called Emmanuel (“God is with us”), betrays no surprise at the divine command which assigned to the son of Mary a different name, from which it is to be inferred that he regarded Jesus and Emmanuel as equivalent.

Guignebert anticipates the argument that this mention of Emmanuel actually is an indicator that Jesus really was given the name of Jesus at his birth.

Otherwise, had his followers christened him, they would have sought to make the application of the prophecy more direct by calling him Emmanuel rather than Jesus. The answer to this is that the Christians were not immediately aware of the use to which the text Isaiah could be put, and that apparently before they discovered it, the name Jesus had already become established as signifying the Messiah, the Soter, and, in Paul, the great Instrument of God’s work. (pp. 78-79)

It is very probable

We cannot say positively that [the substitution of a sacred name for his human one] did take place, but it is very probable.

It would be perfectly consistent with the process of “mythication” which the whole figure of Christ underwent, and which is already manifest in the Gospels.

From its very beginning, the tradition tended to efface the facts of the life of Jesus prior to the commencement of his mission. (p. 79, my formatting and emphasis)

Guignebert is using here an argument that is consistent with what has since been formulated as a “criterion” of authenticity. CG is pointing out the reason we should doubt, or certainly question and accept only tentatively, the authenticity of the name “Jesus”.

Robert Funk’s second criterion by which we might assess the authenticity of some detail in the Gospels states:

On the other hand, anything based on prophecy is probably a fiction. It is clear that the authors of the passion narrative had searched the scriptures for clues to the meaning of Jesus’ death and had allowed those clues to guide them in framing the story: event was made to match the prophecy. (p. 223 of The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus)

Paula Fredriksen expressed the same principle in another context this way:

Actual history rarely obliges narrative plotting so exactly: Perhaps the whole scene is Mark’s invention. (p. 210 of Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jew)

In other words, if Joseph and Mary really did give the name Jesus to their baby it was a stroke of good luck that the name proved to be so apt for one who, after his death, was thought to be the Son of God, Saviour, Healer of mankind and suitably named successor to the Mosaic order. On the other hand, it would be perfectly consistent, whether one believes in the historical Jesus or not, for the name to have been especially chosen and applied to the one who was to be signified as Saviour, Healer, successor to the Mosaic cult, etc.

Back to Gullotta’s review

Daniel Gullotta repeats a common refrain that the name Jesus would not be a likely choice for an exalted heavenly being. He points to the silence in the Jewish record. The above work, the information brought to the table by John Moles and the questions asked by Charles Guignebert, show that Gullotta’s “problem” is not necessarily resolved by rhetorical questions and appeals to silence within a Jewish culture sealed off from its wider Hellenistic-Roman environment. The fact remains that Jews did indeed exalt the name Jesus to be worthy of a heavenly figure deserving of worship.

The question then becomes: Why did the name Jesus become exalted? Was it because his followers wanted to retain his very common name despite its anomalous character in the “pantheon”? And if it could be maintained out of lack of imagination or stubborn loyalty to a memory, then we open the equal likelihood that the same name might even have been adopted for rich magical or other meaningful reasons. Then the question to ask is if it was maintained or adopted for reasons that comported with the mythical figure “Jesus” had become and was very apt for a range of cultural reasons in that Greco-Roman world?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

You say “What is the historical Jesus had been named Simon ..?” but I think you mean if.

Feel free to delete this post (best to?)

Thanks. I do appreciate little notices like this.

Clark is just too ordinary a name for Superman. Harry Potter is just too ordinary a name. Raphael is too ordinary a name for a renaissance artist. What a stupid argument.

Why did the name Jesus become exalted? One possible reason is that the Gentiles creating this new theology out of the LXX were not Jews and did not live in Palestine; therefore, they had no idea that it was a common, mundane name. They only knew the LXX context, and they knew the Greek equivalent meant “healer.” “Christ the healer” is indeed an appropriate name for an angelic being who assumes human form to heal people.

What must it be like to live in an ancient culture where people had literal names?

Hi, my name is Warrioro, it means warrior.

Plenty of people have literal names in modern cultures, in all languages I know of including English. Maybe you mean “where most people had literal names” or “where the vast majority of names were literal”.

And of course a literal name involves the actual literal word, not the word with an “o” stuck at the end. So, “Warrior”.

On that note, “Martial” is a legit first name in French and apparently Spanish.

I was being mocking, since most Christians have Biblical names, and most Christians don’t know what they mean.

So Rylands:

It is easy to understand why the name Jesus should have eventually displaced all the other names under which Gnostics worshipped the Logos, seeing that Jesus signifies helper, healer, or saviour. This name would suggest the Greek word “ Iesis ” = healing. Iaso (genitive Iasous) was goddess of health and daughter of Asclepios. Jason, again, was revered as a divine being in Thessaly and on the borders of Asia, and was regarded as a healer or saviour. The name Jason was, in fact, taken as a Greek equivalent of Joshua.2

(Did Jesus Ever Live?, p. 84)

The note 2 says:

Josephus, Antiquities, xix. v. i.

Was the name “Jacob” more common that Jesus? https://vridar.org/2010/10/28/israel-jacobjames-an-archangel-created-before-all-other-creation/

Melchitzedek doesn’t conform to how angels are named…

Ilan’s Lexicon lists James/Jacob as the 11th most popular male name in Palestine between 330 bce and 200 ce. Joshua/Jesus ranks #6.

Just curious. Why isn’t David on this list?

A word of warning: Names are tricky things and it’s possible to read too much into them.

For example, the name ‘Carrier’ could be linked to ‘messenger’ or ‘someone who has a deadly virus’ but this would be a linguistic coincidence. Carrier accepts that he exists, I think. Even though he may well be spreading a theory that might infect traditional Christian belief.

Likewise, I’m studying the accuracy of the WW2 Desert Campaign produced by Official Historians and one of my important sources is Playfair. Sounds too good to be true. But he was real.

There is that weird phenomenon of nominative determinism. I have been diagnosed with Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) and a world expert in DISH happens to be the Canadian scientist Dr Bone!

Richard Pervo is a rather unfortunate name for a New Testament scholar, especially in light of his extracurricular interests. But that doesn’t negate his existence.

All that is true, but I don’t think Carrier is arguing that Jesus having a significant name *proves* he was mythical. In a Bayesian analysis the important thing is the balance of probabilities. Both real and imaginary people can have names that can fit some aspect of them to an unusual degree. The question is, is there more of one or the other?

I haven’t seen statistical studies, but offhand I’d think the fact real people with really on-the-nose names are considered “weird” or “too good to be true” suggests it’s fairly unusual overall (of course there’s a continuum of *how* well a person’s name fits some aspect of them; but I think one can say that there are levels of fit that really are unusual, and I think Carrier would argue that’s the level of fit being discussed here). I’d also think that the phenomenon is less unusual in fiction, given authors get to choose both the name and the character, and choosing on-the-nose names is a well-known stylistic choice. So I wouldn’t be surprised if out of all the people with an absurdly on-the-nose name, more are fictional than real. And if that’s the case, then “having an on-the-nose name” would be legitimate evidence for someone being fictional. How strong a piece of evidence it is would depend on the differential between how many people with on-the-nose names are fictional vs real.

Maybe that is exactly what you were arguing, that real people with appropriate names are common enough that the differential is small and so it’s weak evidence?

” the name ‘Carrier’ could be linked to ‘messenger’ or ‘someone who has a deadly virus’ but this would be a linguistic coincidence. Carrier accepts that he exists, I think.”

But there are no popular stories in circulation about him being a messenger or spreading disease, are there?

The coincidence is significant, not the name itself, and while the coincidence alone doesn’t prove anything decisively, it still adds to the probability the name is made up.

It would be interesting to find Guignebert having a view on Philo’s view of Zechariah 6, regarding the names Jesus, Branch, and Logos.

This issue of common names for angels is worth very little if Philo, in fact, uses Jesus as such.

He doesn’t.

I am unsurprised to see you writing about Gullotta’s response, of course. Am I unsurprised that mythicists take great difficulty to get published? Iesous means ‘Yahweh saves’, of course it contains a theophoric element, but that isn’t the same as being an *exalted* name. Almost all the other common names at the time had theophoric elements at the time. Lazarus means ‘God has helped’. Joseph means ‘Yahweh/Jehovah adds/increases’ (I may not be getting the exact etymology here). Matthias means ‘Gift of God’. Practically all names in any period in any ancient civilizations contained theophoric elements — just like at some Egyptian names, like Ramses (born of Ra), Thutmose (born of Thut), Ptahmose (born of the god Ptah), etc. The same applies for Hebrew names, Akkadian names, Ugaritic names, etc, etc, etc. These aren’t exaltations, and having an etymological relationship with the word ‘healer’ isn’t an exaltation either. John, another “common name” you mentioned, in fact means ‘Jehovah has been gracious’ (again, I may not be getting the exact etymology).

There’s nothing exalted about these names, it was simply a common ancient custom to imbed the name of the deity into the name of your child. That’s why today, in the Arab world, you have many people whose name is Abdullah — which means “slave of God”. There are so many theophoric Arab names that you can go through an entire list here on Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Arabic_theophoric_names

None of these names are exalted, and an etymological relationship with healing isn’t an exaltation either. Indeed, the real exaltation for an angel would be embedding the theophoric element *El* into the name. That’s why, as Gullotta points out, a change that occurred in the Second Temple Period is the fact that the theophoric element el entered into almost all angel names — Raphael, Uriel, Michael, etc. Jesus is an incredibly unlikely angel name. In fact, we don’t need to appeal to any exaltation/pun/whatever to explain Jesus’ name, because, in fact, ‘Jesus’ was the 6th most common name in Jesus entire period. And, as Gullotta points out, *every* person named Jesus was a man in this time.

“Daniel Gullotta repeats a common refrain that the name Jesus would not be a likely choice for an exalted heavenly being.”

But this is wrong. Gullotta’s argument is that Jesus would not be a likely choice for an exalted **archangelic** being, which is what Carrier maintains. And he’s absolutely right. Analyzing the fantastical silence of the archaeological record of the entire Mediterranean world, and the known naming customs of angels in the Second Temple Period, Carrier’s thesis is significantly improbable.

You quote Gulotta almost verbatim.

Yeah, the majority of angels had names ending with ‘el’. To make much of this fact is just desperate.

Anyway, Carrier just responded on his blog, if anyone interested, he adresses this issue too.

“Yeah, the majority of angels had names ending with ‘el’. To make much of this fact is just desperate.”

Typical mythicist apologetics. It’s not just a majority, it’s an overwhelming majority, and it reflects a well-established naming customs of angels in the Second Temple Period established by scholars. For example, consider these texts from the pre-Christian work of 1 Enoch.

1 Enoch 6:6-7: And they were in all two hundred; who descended ⌈in the days⌉ of Jared on the summit of Mount Hermon, and they called it Mount Hermon, because they had sworn and bound themselves by mutual imprecations upon it. 7. And these are the names of their leaders: Sêmîazâz, their leader, Arâkîba, Râmêêl, Kôkabîêl, Tâmîêl, Râmîêl, Dânêl, Êzêqêêl, Barâqîjâl, Asâêl, Armârôs, Batârêl, Anânêl, Zaqîêl, Samsâpêêl, Satarêl, Tûrêl, Jômjâêl, Sariêl. 8. These are their chiefs of tens.

Out of the 19 angels named, 16 of them have names ending with the theophoric element ‘el’. And consider this one as well:

1 Enoch 20:1-8: And these are the names of the holy angels who watch. 2. Uriel, one of the holy angels, who is over the world and over Tartarus. 3. Raphael, one of the holy angels, who is over the spirits of men. 4. Raguel, one of the holy angels who †takes vengeance on† the world of the luminaries. 5. Michael, one of the holy angels, to wit, he that is set over the best part of mankind ⌈⌈and⌉⌉ over chaos. 6. Saraqâêl, one of the holy angels, who is set over the spirits, who sin in the spirit. 7. Gabriel, one of the holy angels, who is over Paradise and the serpents and the Cherubim. 8. Remiel, one of the holy angels, whom God set over those who rise.

Out of all seven angels named, **all** of them end with the theophoric element el. Gullotta noted these two texts in his footnotes. Furthermore, there is not a single record in the entire Mediterranean, not one, which has any reference to an angel named Jesus. This makes it significantly improbable that there was any archangel named Jesus. Furthermore, Paul tells us Jesus isn’t an angel in Romans 8:37-39, where he distinguishes between created things (explicitly including angels) and Jesus.

“Anyway, Carrier just responded on his blog, if anyone interested, he adresses this issue too.”

In Carrier’s response, he basically admitted that Gullotta was right on this point. He basically just says “OK, the angel wasn’t named Jesus — the fact still remains Jesus was based on some angel regardless of its name”. Where Carrier gets this ‘fact’ from is beyond me, but Carrier basically conceded this point to Gullotta. Have you even read Gullotta’s paper?

‘He [Carrier] basically just says “OK, the angel wasn’t [specifically] named Jesus — the fact still remains Jesus was based on some angel regardless of its name”. Where Carrier gets this ‘fact’ from is beyond me ..’

You would need to fully read what Carrier has written on this point, but it is essentially exegesis ( and perhaps eisegesis) of Philo and of LXX passages that Philo alludes to (by quoting them, at least). Carrier has given specific references of a few passages.

Carrier says, in his bog-post reply to Gullotta –

I quote Philo saying this archangel had “many names.” Gullotta can’t claim to know what all of them were. Philo doesn’t tell us. The only name he ever mentions this angel having, is Anatole (Rising One). Notably, not ending in el …

.. Philo interprets the Jesus in Zechariah 6 as this angel, he clearly believed this angel wasn’t just named Anatole but also Jesus. Gullotta gives no argument against this obvious point. In fact, Philo identifies him as Jesus “the son of God.” His firstborn son, even. And likewise he was named Adam —as Philo explains this archangel was one of the Adams referred to in Genesis. Lots of names (as Philo says) were given to this archangel.

Carrier says ‘Philo’s angel is the same being the first Christians thought their Jesus was.’, but I think he would have been better to say –

Philo’s angel is identical to (or very similar to) the being the first Christians thought their Jesus was.

Carrier, as has been shown, utterly rips Philo and Zechariah out of their meaning. Philo is supposed to believe that Zechariah mentions the anatole, a rising branch and Son of God, named Joshua (Jesus). There is no such figure in Zechariah, Zechariah is describing two different figures.

Zechariah 6:9-14: The word of the Lord came to me: 10 “Take silver and gold from the exiles Heldai, Tobijah and Jedaiah, who have arrived from Babylon. Go the same day to the house of Josiah son of Zephaniah. 11 Take the silver and gold and make a crown, and set it on the head of the high priest, Joshua [Jesus] son of Jozadak.12 Tell him this is what the Lord Almighty says: ‘Here is the man whose name is the Branch, and he will branch out from his place and build the temple of the Lord. 13 It is he who will build the temple of the Lord, and he will be clothed with majesty and will sit and rule on his throne. And he will be a priest on his throne. *******And there will be harmony between the two.’******* 14 The crown will be given to Heldai, Tobijah, Jedaiah and Hen son of Zephaniah as a memorial in the temple of the Lord. 15 Those who are far away will come and help to build the temple of the Lord, and you will know that the Lord Almighty has sent me to you. This will happen if you diligently obey the Lord your God.”

See? “And there will be harmony between the two” — between the two WHO? Obviously, Joshua on the one hand, and the anatole (branch) on the other. These are two separate people. Carrier admits this, but claims that Philo didn’t know this and conflated the two. Of course, anyone who reads Philo’s text will see no evidence that this conflation ever occurs, as Larry Hurtado has pointed out. Philo says:

“I have also heard of one of the companions of Moses having uttered such a speech as this: “Behold, a man whose name is the East!”{18}{#zec 6:12.} A very novel appellation indeed, if you consider it as spoken of a man who is compounded of body and soul; but if you look upon it as applied to that incorporeal being who in no respect differs from the divine image, you will then agree that the name of the east has been given to him with great felicity. (63) For the Father of the universe has caused him to spring up as the eldest son, whom, in another passage, he calls the firstborn; and he who is thus born, imitating the ways of his father, has formed such and such species, looking to his archetypal patterns.” On the Confusion of Languages 62-63

Anyone can read it for themselves. Carrier points out that Philo calls the anatole an archangel, but this figure is never conflated with Joshua. There is not a figment of evidence anywhere in Philo’s text where he refers to any archangel named Jesus. You note that Carrier writes this:

“I quote Philo saying this archangel had “many names.” Gullotta can’t claim to know what all of them were. Philo doesn’t tell us.”

Argument from silence. Philo never mentions an archangel named Jesus. As Gullotta has pointed out, there isn’t one strand of archaeological evidence in the entire ancient Mediterranean of any angel named Jesus, and furthermore, a custom of the Second Temple Period would be to include the theophoric element *el* in the archangelic name, and of course, Jesus does not contain this theophoric element, and so is a very weak candidate for an angelic name. In other words, there’s no evidence for any angel named Jesus and such a name would contradict what know about angelic names in that period anyways.

Perhaps the most important factor to consider is that Paul actually *tells us* Jesus isn’t an angel.

Romans 8:37-39: No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. For I am convinced that neither death nor life, **neither angels** nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, **nor anything else in all creation**, will be able to **separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord**.

Paul explicitly tells us that nothing in creation, including angels, will act as a separation between us and Jesus. Bart Ehrman had made the same angelic claim about Jesus some other time, which has been refuted by appeal to this verse. Paul *tells us* Jesus isn’t an angel.

Considering all this evidence, I’d suppose this is checkmate. Mythicist apologetics requires a very rigorous knowledge of the facts in order to circumvent and may catch the unknowing reader by surprise. Thankfully, scholars are more informed by that. I’d recommend you actually read Gullotta’s paper and then read Carrier’s response to see if it makes much sense, and focus on just how many concessions Carrier makes in his response.

[Edited at author’s request…. Neil Godfrey, Feb 2024]

It’s supposed to be ironic trolling to accuse mythicists of being apologists? It’s sort of like how “creation scientists” accuse science of being a religion.

Christians spend the live long day ripping OT content out of context. That’s apologetics.

Christianity has not ever been a monolithic unchanging belief system. It’s ironic to even suggest that mythicism is “unconvincing” when many actual Christian sects held this to be true.

to Jimmy –

1. re ‘ “And there will be harmony between the two” — between the two ‘Who’? ‘

Either

a/ Harmony between (11) the high priest, Joshua [Jesus] son of Jozadak and (12) the Lord Almighty, or

b/ Harmony between (11) the high priest, Joshua [Jesus] son of Jozadak and (13) the throne (in the temple of the Lord), or

c/ Harmony between three or four of these entities: Joshua, the Lord, the throne, and the temple [of the Lord]

________________

You cite On the Confusion of Languages 62-63 but, like Hurtado, fail to cite or acknowledge On the Confusion of Languages 145-7 –

(145) they who have real knowledge, are properly addressed as the sons of the one God, as Moses also entitles them, where he says, “Ye are the sons of the Lord God.”{41}{#de 14:1.} And again, “God who begot Thee;”{#de 32:18.} and in another place, “Is not he thy father?” Accordingly, it is natural for those who have this disposition of soul to look upon nothing as beautiful except what is good, which is the citadel erected by those who are experienced in this kind of warfare as a defence against the end of pleasure, and as a means of defeating and destroying it. (146) And even if there be not as yet any one who is worthy to be called a son of God, nevertheless let him labour earnestly to be adorned according to his first-born word, the eldest of his angels, as the great archangel of many names; for he is called, the authority, and the name of God, and the Word, and man according to God’s image, and he who sees Israel. (147) For which reason I was induced a little while ago^^ to praise the principles of those who said, “We are all one man’s Sons.”{#ge 42:11.} For even if we are not yet suitable to be called the sons of God, still we may deserve to be called the children of his eternal image, of his most sacred word; for the image of God is his most ancient word. http://www.earlyjewishwritings.com/text/philo/book15.html

You might want to look up the word ‘apologetics’.

A majority is not all, whatever adjectives you choose to spice it up, it gets you only this far.

And that’s about second temple Hebrew stuff, so what do you expect of some epistles of unclear origins composed in Greek, belonging to the ‘ramblings of a madman’ genre?

Anyway, even before Philo already named his angels whatever he damn well pleased.

Desperate.

You failed to understand his response then.

Fyi — “Jimmy” began ringing too many memory bells of another “jimmy” or whatever some years ago who insists he’s a most dogmatic fundamentalist and by no means the same person as Tim O’Neill — I have no idea and don’t care. He’s a troll; a waste of time. I have put him on my spam list.

If you really want to continue a discussion with this person I am sure Tim O’Neill can put you in touch. The two have indicated in the past that they are “very close”. Check his “History for Atheists” blog or website.

Re Jimmy — I ran his comments through a “linguistic inquiry and word count” (LIWC) analyser and compared the results with recent comments and posts by Tim O’Neill from five different websites and blogs. As expected, the results of the five Tim O’Neill writings were all very similar. What was interesting, then, was to find that Jimmy’s literary “fingerprints” were virtually indistinguishable from Tim O’Neill’s. Now that does not prove the two persons are the same. The LIWC tool is not perfect. But it does at least seem to indicate that Jimmy and Timmy have remarkably similar literary styles.

There was only one noticeable difference. The Jimmy comments here on Vridar showed a marked increase in expressions of a drive for achievement over the Tim O’Neill writings. If the two are the same perhaps this might indicate that Tim came here as Jim to defend and prove himself against posts that were directly and indirectly critical of his own ideas.

But maybe it’s all just a coincidence. We can’t really know.

(Jimmy has not attempted to post to this blog since my last comment alerting him to my recollections that I had come across him before, along with his close support of Tim O’Neill’s posts.)

So if Jesus was such a common name why was the person with that name exalted to a rank second only to God without a change in name? Wouldn’t it be like worshiping Lord Fred or something sounding similarly crass?

I admire your persistent ability to simply ignore arguments you don’t like and merely repeat mantras as if nothing else has ever been said (or posted). You’re very good at that, Jimmy.

You also wrote that I was wrong re what Gullotta said about the name Jesus and that he was talking only about the name of archangels, or something to that effect. I thought most readers would have noticed that I only use a selected passage from Gullotta’s review to raise another and more broad point, one that Gullotta’s words tie in with very well, and one that is frequently raised as an argument against the Christ Myth theory. I was not addressing Gullotta’s review but using a passage from it to introduce a more general question. There’s nothing wrong with doing that.

You should notice that the entire post was addressing that broader question and at no point turned back to address Gullotta’s specific argument about archangels and Philo etc. I have no interest in that particular argument.

You know, when you read books you sometimes see a quotation at the head of a new chapter that introduces a theme that is to be taken up in that chapter. Often that quotation is taken from its larger context and is used for the utilitarian value of the particular words used. That’s what my post was doing.

I would expected most readers to have that sort of reading comprehension ability. You remind me of another visitor to this blog who had very similar casuistic and sophistic criticisms of my comments. He and O’Neill also used to defend each other.

Your willingness to find fault in my comments by ignoring what I do say (as in my post on Nixey) and reading into them what I don’t say (as here) really does indicate you have no interest in serious discussion but in manufacturing faults to hit me with.

Clark Kent should have changed his name to something, … something exalting, like Superman, or something.

عَلِيٌّ ie ‘Alē is a commun arabic name – meaning ‘ixoltid’ or the ‘very high’

esp commun amungst the shē’ēs. A shē’ē sect actually thought Alē was god – and part of the muslim trinity – cunsisting in Muhammad, Fatima and Alē.

prhaps lejndrily: Abdullah b Saba a yemenē jewish convurt told Alē ‘You are you’ – meaning Alē is the ‘I AM’ (isa 43; 51 -ego eimi ego eimi “I’m I AM”).

A funny fact, we can’t even be 100% sure the name was Jesus initially.

All ancient manuscripts abbreviate his name ‘IC’ or similar, oldest inscriptions saying ‘Iesous Chrestos’ pop out in archeological record at around fourth century, if I’m not mistaken.

Evidence exists, suggesting the title Chrestos had been changed to Christos, what if they also forgot what the name was, and reinvented it later?

Anyway, common name or not, the fact they wrote it in nomina sacra, just as they did God, Lord and Spirit, says a lot about how they saw that figure.

“Daniel Gullotta repeats a common refrain that the name Jesus would not be a likely choice for an exalted heavenly being. He points to the silence in the Jewish record.”

…..It is interesting that of all the Jewish apocryphal literature Joshua never figures as the main character. There’s Adam, Seth, Elijah, Ezra, Isaiah, Baruch etc, etc but no Joshua.