–o0o–

I am sure most students familiar with the Bible who take up reading the literature of Classical and Hellenistic Greece at various points pause and wonder at some striking similarity between the two literatures. Are those similarities merely coincidental or the inevitable product of a common cultural milieu or is there some other explanation? In delving into the details of some of those points in common Russell Gmirkin concludes that the authors of the biblical narratives, including the law codes, had access to the wealth of Greek literature at the Great Library of Alexandria in the Hellenistic Age, that is, from some time after death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE.

Russell Gmirkin (Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible) compresses so much information into his chapters that I need to regularly pause from reading and start the work of unpacking his citations and endnotes in order to fully appreciate just how interesting his case is. After surveying the range of literary genres in which Greeks expressed their partiality towards narratives providing backgrounds to the origins of their constitutions and laws he decides to focus on the Greek foundation narrative as being the closest in form to what we find in the Pentateuch.

The foundation story most of us are probably aware of is the Roman epic, the Aeneid, the story of the wanderings of Aeneas from the fallen Troy to seek a new land in Italy. Don’t let the “post-biblical” date of Virgil’s composition mislead you, though, since

It should be clear, first of all, that the Aeneas legend and the stories associated with it are quite ancient and may be traced back — as the various paintings on archaeological artifacts show — to the seventh century B.C.E. That these stories actually belong to the genre of “foundation stories” about foundations of cities by single heroes has been noted by F. B. Schmid, who surveyed the foundation legend of the Greeks, and observed that the Aeneid epic was patterned after them.[39] (Weinfeld 1993, pp. 16f)

Most of us have heard of the voyages of the Argonauts and this story also contains within it the beginnings of another foundation story, that of Cyrene. After trekking through an African desert in a quest sometimes eerily echoing the story of Israel’s wandering in Sinai, a son of the god Poseidon gives Euphemus, one of the Argonauts, a clod of earth as a sign that his descendants will return and possess the land of Cyrene.

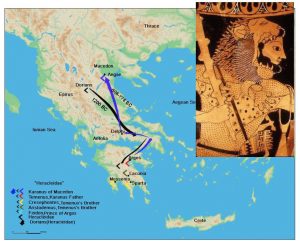

The Spartans believed themselves descendants of the sons of Heracles who, long after Heracles himself had left the earth and not unlike the Israelites under Joshua, invaded the Peloponnesian peninsula to claim it as their own land as promised by Zeus to their illustrious forefather.

Motifs commonly found among the foundation myths as taken primarily from Gmirkin’s discussion but with a few touches added from some of the sources he cites:

-

A hero leaves a settled home to wander through new lands

-

A god promises the hero that his descendants will one day possess the land where he is now a stranger

-

After some generations the hero’s descendants face pressures of some kind (plague, oppression, overpopulation, threats of war…) so return to claim (conquer) the land promised to their forefather(s)

-

Sometimes an unforseen delay or setback appears to sidetrack or threaten the expedition on its way to reclaiming their promised land

-

The new conquerors are led by a wise hero who often has had special preparatory experiences (living with the wise, contacts with a god) to qualify him to be their military leader who would lead the expedition as an armed force

-

Often the military leader would be accompanied by a priest or prophet

-

The new conquerors bring their “rightful” god(s) of the land with them; the god would sometimes be consulted throughout the period of migration

-

The leader of the expedition would also give them the laws and political constitution by which their new society was to be governed

-

After conquest land was fairly divided by lot

-

The founder was revered, often with his own cult, and an agricultural festival was turned into a festival commemorating the events of a people’s ancestors migration to and conquest of their land

I will post some of the myths illustrating the above in future posts. (In some myths, such as Aeneas’s mission being realized through Romulus and Numa, a single hero would be replaced by a succession of heroic figures.)

The legends of the founding of Rome, of Cyrene, and of the return of the Heraclidae are three foundation myths but there were many more. A “Judean” foundation myth closest in form to such Greek stories, yet by all appearances is evidently independent of any of our biblical versions of the narratives, is the founding of Israel as told by Hecataeus of Abdera. I posted his narrative a couple of years ago so you can click on Moses and the Exodus According to the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians: Hecataeus or continue reading a fresh copy of his account here. Hecataeus himself wrote in the fourth and third centuries B.C.E. Gbut we owe our thanks to Diodorus Siculus [= of Sicily] of the first century B.C.E. for preserving (via paraphrase) what he had to say:

[3] Since we are about to give an account of the war against the Jews, we consider it appropriate, before we proceed further, in the first place to relate the origin of this nation, and their customs.

In ancient times a great plague occurred in Egypt, and many ascribed the cause of it to the gods, who were offended with them.

For since the multitudes of strangers of different nationalities, who lived there, made use of their foreign rites in religious ceremonies and sacrifices, the ancient manner of worshipping the gods, practised by the ancestors of the Egyptians, had been quite lost and forgotten.

2 Therefore the native inhabitants concluded that, unless all the foreigners were driven out, they would never be free from their miseries.

Greek foundation stories commonly began similarly, that is, with some pressure or calamity in the “home” from which they were compelled to leave.

All the foreigners were forthwith expelled, and the most valiant and noble among them, under some notable leaders, were brought to Greece and other places, as some relate; the most famous of their leaders were Danaus and Cadmus. But the majority of the people descended into a country not far from Egypt, which is now called Judaea and at that time was altogether uninhabited.

3 The leader of this colony was one Moses, a very wise and valiant man, who, after he had possessed himself of the country, amongst other cities, built that now most famous city, Jerusalem, and the temple there, which is so greatly revered among them.

He instituted the holy rites and ceremonies with which they worship God; and made laws for the methodical government of the state. He also divided the people into twelve tribes, which he regarded as the most perfect number; because it corresponds to the twelve months within a whole year.

4 He made no representation or image of gods, because he considered that nothing of a human shape was applicable to God; but that heaven, which surrounds the earth, was the only God, and that all things were in its power.

So far it looks as though Moses is instituting the ways of the most philosophical of the Greeks. But a twist is to come.

But he so arranged the rites and ceremonies of the sacrifices, and the manner and nature of their customs, as that they should be wholly different from all other nations; for, as a result of the expulsion of his people, he introduced a most inhuman and unsociable manner of life.

I don’t know the scholarship on this passage but that last line does jar against the tenor of the rest of the account of Moses that I can’t help but wonder if an anti-semitic hand has found its way into the copyists responsible for our text. I could be quite wrong, of course.

He also picked out the most accomplished men, who were best fitted to rule and govern the whole nation, and he appointed them to be priests, whose duty was continually to attend in the temple, and employ themselves in the public worship and service of God.

5 He also made them judges, for the decision of the most serious cases, and committed to their care the preservation of their laws and customs. Therefore they say that the Jews have never had any king; but that the leadership of the people has always been entrusted to a priest, who excels all the rest in prudence and virtue. They call him the chief priest, and they regard him as the messenger and interpreter of the mind and commands of God.

(Never had a king? See In Search of Ancient Israel if that sounds confusing.)

6 And they say that he, in all their public assemblies and other meetings, discloses what has been commanded; and the Jews are so compliant in these matters, that forthwith they prostrate themselves upon the ground, and adore him as the high priest, who has interpreted to them the will of God.

At the end of the laws this is added: “This is what Moses has heard from God and proclaims to the Jews.”

This lawgiver also laid down many excellent rules and instructions for military affairs, in which he trained the youth to be brave and steadfast, and to endure all miseries and hardships.

7 Moreover, he undertook many wars against the neighbouring nations, and gained much territory by force of arms, which he gave as allotments to his countrymen, in such a way as that everyone shared alike, except the priests, who had a larger portion than the rest; so that, because they had a larger income, they might continually attend upon the public worship of God without interruption. Neither was it lawful for any man to sell his allotment, lest, by the greed of those that bought the allotments, the others might be made poor and oppressed, and so the nation might suffer a shortage of manpower.

8 He also ordered the inhabitants to be careful in rearing their children, who are brought up with very little expense; and by that means the Jewish nation has always been very populous. As to their marriages and funerals, he instituted customs far different from all other people.

But under the empires which rose up in later ages, especially during the rule of the Persians, and in the time of the Macedonians, who overthrew the Persians, through intermingling with foreign nations, many of the traditional customs among the Jews were altered . . .

This is what Hecataeus of Abdera has related about the Jews.

Elsewhere Gmirkin points out that

The Greek tendency was to attribute the most ancient laws to a single legendary, semi-legendary or archaic lawgiver of great repute, such as Minos, Theseus, Lycurgus or Solon (see generally Szegedy-Maszak 1978: 199-209; cf. Hagedom 2004: 83-5). Some of these ancient codes were given added prestige by a tradition wherein the lawgiver received his laws or constitution direct from a god.57 . . . .

Similarly, the oikist [=leader of an expedition to found a new colony or city] acted as religious authority and spokesman of Apollo both during the expedition itself and after the settlement in the new territory (Malkin 1987: 5). Greek colonizing expeditions involved not only the migration of the group of colonists, but also the transfer of its deity60 and his cult . . . .

In both Greek foundation stories and in the biblical narrative, the ancestral constitution and laws were framed by the lawgiver who led the colonizing expedition to the new territory. In this respect, the figure of Moses precisely fulfilled the responsibilities of an oikist.67 . . . . (Gmirkin, pp. 228f)

In future posts we will see that the biblical narrative of the founding of Israel and her laws has many more overlaps with Hellenistic foundation stories.

Gmirkin, R. 2017. Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible. New York: Routledge.

Gmirkin, R. 2017. Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible. New York: Routledge.

Weinfeld, M. 1993. The promise of the land: the inheritance of the land of Canaan by the Israelites. Berkeley: University of California Press.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Gmirkin in Berossus p. 63 summarizes what he believes Hecataeus acount is. The anit-Semitic account he claims that comes from Theophanes. He writes:

“Hecataeus only wrote one foundation story of the Jews, favorable to the point of utopianism; the negative elements in Book40 are all to be explained by Theophanes’ inclusion of anti-Semitic traditions deriving from Manetho.”( p. 64 )

Criticism on Gmirkin can be found in L. L. Grabbe (ed.) “History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period – Volume 2”

Gmirkin’s answer can be found in Thomas L. Thompson (ed.), Philippe Wajdenbaum (ed.) “The Bible and Hellenism”

I guess this is why Gmirkin in (Plato) writes in the first line of his introduction :

“This book is a sequel to Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch”.

I wish Gmirkin is reading this thread and can enlighten us on the matter.

Thanks for the reminder. I will have to go back and check the previous work.

I’m as sure any literate person of the time would recognize the similarity as much as the similarity to Gilgamesh, and that no one would write anything about it for the same reason they don’t today.

I was surprised to learn from Gmirkin’s citations that scholars have published about the similarities for some time now. I will post some details in my next post.