Ever since the early 1960s biblical scholars and even psychologists have been told something very critical about the apostle Paul’s teachings that had the potential to spare the mental sufferings of so many Western Christians. Paul did not teach that one had to go through self-loathing or guilt-torment in order in order to be saved by faith in Christ’s forgiveness. That guilt-focused teaching came to us primarily via Augustine and Luther. It was a teaching that can nowhere be found in reference to Paul in the first 350 years of Christianity.

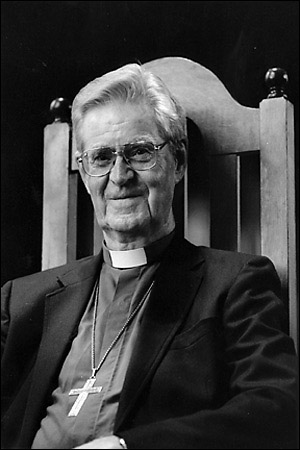

That is the argument of Krister Stendahl in a paper, “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West” (The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Jul., 1963), pp. 199-215) said to be a watershed in Pauline studies. But the real-world relevance of the paper is indicated by the fact that it was first delivered two years earlier “as the invited Address at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, September 3, I961.”

I’ve had the paper sitting in my files waiting to be read for some time now, and only dug it out after seeing it cited by James W. Thompson in The Church According to Paul: Rediscovering the Community Conformed to Christ (2014).

Paul, Thompson claimed, never addressed personal struggles with tormented conscience that could only be resolved by desperately throwing oneself upon the mercy of Christ:

The first-person singular pronoun is a consistent feature of church music in the evangelical tradition.

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound

that saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now, found,

Was blind but now I see.

Like countless other songs in this tradition, “Amazing Grace” tells of the individual who was lost in sin, unable to meet God’s demands until Jesus paid it all at the cross. These songs echo Pauline themes of sin, grace, and justification. Indeed, Paul’s legacy is the good news that we have been “justified by faith’ (Rom 5:11. not by our own works (cf. Rom. 3:20, 28; 4:2). In the cross God demonstrated righteousness for all who believe (Rom. 3:21-26). The death of Christ “while we were yet sinners” (Rom 5:8 KJV) was the expression of God’s love.

Interpreters have maintained that this narrative mirrors Paul’s own experience. According to this view, Paul struggled with a guilty conscience, having attempted in vain to keep the law perfectly. The “wretched man”(Rom. 7:24) who could not do the good or keep the law was Paul himself, who lived within the context of a form of Judaism that had degenerated into a legalistic and hypocritical religion that no longer recognized the mercy of God and instead emphasized meritorious works. Paul then found the answer in the grace of God and recognized that God justifies the ungodly. Paul has often been regarded as paradigmatic for those who discovered God’s grace when they could not keep God’s commands. When he met Christ on the Damascus road, he experienced God’s grace. Out of this experience, he became the example of the path of conversion for all subsequent generations and the major theme of his writings is justification by faith. This view has been emphasized in Protestant theology, becoming the popular theme of revivalists and Christian song writers.

Krister Stendahl observed that the Pauline doctrine of justification by faith did not emerge as the center of Paul’s theology until Augustine, who himself turned to Paul after struggling with a guilty conscience. Augustine found the solution to his own personal struggle in the grace of God! Luther also discovered the grace of God as the solution to his own desire to find a merciful God. Beginning with Luther, the Reformers maintained that Paul’s doctrine of the righteousness of God was the center of the gospel. This doctrine has been conceived in individualist terms. . . . For numerous Protestant theologians, justification was the salvation of the individual. . . . The good news is the righteousness of God that rescues individuals from their lost condition. (Thompson, pp. 127-128)

That’s exactly what I have understood all these years. I had to set aside Thompson and get back to the Stendahl article he cited as my first step in addressing immediate questions that come to mind. Didn’t Paul cry out in desperation in Romans 7 that he struggled helplessly against his body of sin? No, he didn’t — as Stendahl pointed out. Paul spoke of a body of “death” but not “sin”. But, but …. Okay, I’ll try to hit the highlights of the article. Many readers are no doubt already well familiar with it. A web search will point to many discussions about the article online. So I will try to focus on the points that I found salient.

It’s all Augustine’s and Luther’s fault

The quotes are from Stendahl’s article in the HTR and all highlighting and some formatting is my own:

Especially in Protestant Christianity – which, however, at this point has its roots in Augustine and in the piety of the Middle Ages – the Pauline awareness of sin has been interpreted in the light of Luther’s struggle with his conscience. (Stendahl, p. 200)

But in Philippians 3 we read Paul clearly stating he had a very clean conscience at the time of his “conversion”. (Stendahl speaks of Paul’s “robust” conscience.) He boasts that he had always been flawless concerning the righteousness of the law! He was blameless when it came to the righteousness of the law.

as to righteousness under the law blameless. (3:6)

What Paul wanted to put behind him (Philippians 3:13) after he “found Christ” was not a past sinful nature but his past righteous character of which he could proudly boast.

The Law of the Judean scriptures really did allow for human weakness and made provisions for repentance and for God to bestow mercy and forgiveness. The view that the Law was viciously rigorous that led to a sterile, unspiritual subservience to “the letter” without mercy is a misguided caricature. Paul did not think that was a fair description of the Law. So although he could point out in Romans 2-3 the simple truism that it is impossible humanly to keep the law’s precepts perfectly, he nonetheless could boast that he was blameless concerning the righteousness of the law.

Paul’s point was not that the law itself was “bad” (we know he said it was “holy, just and good”) but that even with its provisions for forgiveness, mercy and grace, it no longer served any purpose for salvation.

In Romans 2-3 Paul is not talking about individual Jews or gentiles. They all stand outside of God’s salvation. The Jews as a whole failed to live up to the law just as the gentiles had also failed on the whole to live morally.

Yes, the Jews did have a certain advantage of the gentiles insofar as they were the custodians of the “oracles of God”. They had the law and if they disobeyed that law then they were still privileged because the law also had provision for repentance and mercy. But what the law did not give them was any advantage when it came to salvation through Christ.

When it came to the question of salvation, gentiles ignorant of the law and Jews with the law were equally lost. A new way of salvation had been opened up through Christ and that left Jews and gentiles on an equal footing. And that applied to Jews who were “blameless in the righteousness of the law” (as was Paul personally) although collectively the Jews were sinners just like the gentiles.

It is also striking to note that Paul never urges Jews to find in Christ the answer to the anguish of a plagued conscience. (p. 202)

Paul does not express any personal torments over a guilty conscience as we later read about in Luther’s story.

This is probably one of the reasons why “forgiveness” is the term for salvation which is used least of all in the Pauline writings.5 . . . .

5 There is actually no use of the term in the undisputed Pauline epistles . . . . (p. 202)

Paul’s message turned into its opposite by later generations

The problem Paul confronted was not how to reconcile, since the revelation of Jesus Christ, personal consciences with the legalistic demands of a righteous God. No, the question he addressed was what the revelation of Jesus Christ meant for relations between Jews and gentiles. Understood this way, Romans 9 to 11 about the salvation of both Jews and gentiles becomes the climax of the letter and not a mere appendix, Stendahl notes.

The author of Acts likewise understands this point. In Acts Paul does not come to a conversion after a personal conviction of being a terrible sinner who has disobeyed the laws of God and who is then called to preach to the gentiles. He is called from being blameless concerning the righteousness of the law to begin preaching to the gentiles. No dark-night of the soul or tormented conscience involved at all. His sin, the only sin for which he classed himself as the chief of sinners, is that he persecuted the church.

Translators have been caught up with the Lutheran view of the law, too, when they express Galatians 3:24 as

The law was our schoolmaster (KJV, RV, ASV) to bring us to Christ.

The Revised Standard Version is more accurate with

So that the law was our custodian until Christ came.

Paul did not say (as did Luther) that the law was our tutor. It was not given to make everyone feel hopelessly sinful and personally inadequate against some impossible Pharisaical demand.

Rather, Paul figured out that the Law did not exist until 430 years after the promise to Abraham and that it had a use-by date, the time of the revelation of the Messiah (Galatians 3:15-22).

Hence, its function was to serve as a Custodian for the Jews until that time. Once the Messiah had come, and once the faith in Him – not “faith” as a general religious attitude – was available as the decisive ground for salvation, the Law had done its duty as a custodian for the Jews, or as a waiting room with strong locks (vv. 22f.) Hence, it is clear that Paul’s problem is how to explain why there is no reason to impose the Law on the Gentiles, who now, in God’s good Messianic time, have become partakers in the fulfillment of the promises to Abraham (v. 29).

In the common interpretation of Western Christianity, the matter looks very different. One could even say that Paul’s argument has been reversed into saying the opposite to his original intention.

- Now the Law is the Tutor unto Christ. Nobody can attain a true faith in Christ unless his self-righteousness has been crushed by the Law. The function of the Second Use of the Law is to make man see his desperate need for a Savior. In such an interpretation, we note how Paul’s distinction between Jews and Gentiles is gone. “Our Tutor/Custodian” is now a statement applied to man in general, not “our” in the sense of “I, Paul, and my fellow Jews.”

- Furthermore, the Law is not any more the Law of Moses which requires circumcision etc., and which has become obsolete when faith in the Messiah is a live option – it is the moral imperative as such, in the form of the will of God.

- And finally, Paul’s argument that the Gentiles must not, and should not come to Christ via the Law, i.e., via circumcision etc., has turned into a statement according to which all men must come to Christ with consciences properly convicted by the Law and its insatiable requirements for righteousness.

So drastic is the reinterpretation once the original framework of “Jews and Gentiles” is lost, and the Western problems of conscience become its unchallenged and self-evident substitute. (pp. 206-207)

To my mind those words by Stendahl are extremely significant. It has a lot to say about the damage so much of Christianity has done psychologically to so many. I also like his point about faith not being “a general religious attitude”. The mind-games that are necessary to play that game!

Was Paul bothered by a troubled conscience over his “sin” of persecuting the church? Nowhere does he express contrition for this past program (Gal. 1:13; Phil 3.6; 1 Cor. 15:9). The pseudo-Pauline letters (1 Tim. 1:15, 12-16) and Acts (chs 9, 22, 26) convey the same message. Rather, he boasts that God chose him despite his ignorance that led him to become a persecutor, and he reminds all readers that he has made up for any damage he ever did:

his grace toward me was not in vain. On the contrary, I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I, but the grace of God which is with me (1 Cor. 15:10)

Romans 5:6-11 famously states how Christ died for sinners, etc, but what is too easily overlooked in that passage is that Paul is referencing that sinful life in the past tense. Paul is not requiring people to continue to see themselves as shameful sinners but to be thankful that all past sins are blotted out, just as was the sin of Paul’s persecution of the church.

What did Paul have to say about sins after conversion?

Paul’s letters leave us with no doubt that Paul knew Christians sinned after conversion. His letters often testify to his patience with his converts sins and weaknesses. Did he expect them to flagellate their tormented consciences? The author of Acts certainly didn’t imagine Paul living with such emotional turmoil:

Brethren, I have lived before God in all good conscience up to this day. (Acts 23:1)

The tone of that message, Standahl writes, also pervades Paul’s letters.

Even if we take due note of the fact that the major part of Paul’s correspondence contains an apology for his Apostolic ministry – hence it is the antipode to Augustine’s Confessions from the point of view of form – the conspicuous absence of references to an actual consciousness of being a sinner is surprising. To be sure, Paul is aware of a struggle with his “body” (I Cor. 9:27), but we note that the tone is one of confidence, not of a plagued conscience. (p. 210)

Paul does sometimes speak of his weaknesses, sometimes ironically (2 Cor. 11:21-22), sometimes with proud humility (2 Cor. 12:9-10), sometimes of a thorn in his flesh — but none of these is viewed as a sin for which he is responsible. They were the work of “the Enemy”.

Finally, the verse I was most wanting Stendahl to explain

“I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want to do is what I do” (Rom. 7:19)

Stendahl’s discussion is lengthy and I have already hit on one of his key points above when I pointed out that Paul speaks of a body of “death”. In short, Paul is arguing for the goodness of the Law and in doing so makes the “trivial observation” that everyone knows — that we don’t always do what we know we should. But Paul puts the entire blame on “the flesh” or “sin” and utterly acquits his ego, himself. He himself, he insists, did not want to sin, so he is in the clear.

The argument is one of acquittal of the ego, not one of utter contrition. (p. 212)

For anyone interested in a more detailed explanation I will quote the relevant pages at the end of this post.

Stendahl alludes to outlines of the intellectual and institutional history of the church that appear to have contributed to the modern view that Pauline Christianity focuses on a sense of personal guilt and tortured contrition as a prior condition for salvation: Augustine; the introduction of the regular Mass as a secondary sacrament after baptism; the manuals of self examination produced by the Irish monks and missionaries; the Black Death as a spur for desperate penance; Luther; Wesley; and then the secular successor Freud. Stendahl further notes, interestingly, that such a view of Paul is not part of the tradition of Eastern Christianity.

Detail on Romans 7

Many implications and questions arise, but I will conclude with the detailed explanation of Paul’s argument in Romans 7 (pp. 211-14):

Yet there is one Pauline text which the reader must have wondered why we have left unconsidered, especially since it is the passage we mentioned in the beginning as the proof text for Paul’s deep insights into the human predicament: “I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want to do is what I do” (Rom. 7:19). What could witness more directly to a deep and sensitive introspective conscience? While much attention has been given to the question whether Paul here speaks about a pre-Christian or Christian experience of his, or about man in general, little attention has been drawn to the fact that Paul here is involved in an argument about the Law; he is not primarily concerned about man’s or his own cloven ego or predicament.19 The diatribe style of the chapter helps us to see what Paul is doing. In vv. 7-12 he works out an answer to the semi-rhetorical question: “Is the Law sin?” The answer reads: “Thus the Law is holy, just, and good.” This leads to the equally rhetorical question: “Is it then this good (Law) which brought death to me?”, and the answer is sum- marized in v.25b: “So then, I myself serve the Law of God with my mind, but with my flesh I serve the Law of Sin” (i.e., the Law “weakened by sin” [8:31 leads to death, just as a medicine which is good in itself can cause death to a patient whose organism [flesh] cannot take it).

Such an analysis of the formal structure of Rom. 7 shows that Paul is here involved in an interpretation of the Law, a defense for the holiness and goodness of the Law. In vv. 13-2 5 he carries out this defense by making a distinction between the Law as such and the Sin (and the Flesh) which has to assume the whole responsibility for the fatal outcome. It is most striking that the “I”, the ego, is not simply identified with Sin and Flesh. The observation that “I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want to do is what I do” does not lead directly over to the exclamation: “Wretched man that I am . . .!”, but, on the contrary, to the statement, “Now if I do what I do not want, then it is not I who do it, but the sin which dwells in me.” The argument is one of acquittal of the ego, not one of utter contrition. Such a line of thought would be impossible if Paul’s intention were to describe man’s predicament. In Rom. 1-3 the human impasse has been argued, and here every possible excuse has been carefully ruled out. In Rom. 7 the issue is rather to show how in some sense “I gladly agree with the Law of God as far as my inner man is concerned” (v. 22); or, as in v. 25, “I serve the Law of God.”

All this makes sense only if the anthropological references in Rom. 7 are seen as means for a very special argument about the holiness and goodness of the Law. The possibility of a distinction between the good Law and the bad Sin is based on the rather trivial observation that every man knows that there is a difference between what he ought to do and what he does. This distinction makes it possible for Paul to blame Sin and Flesh, and to rescue the Law as a good gift of God. “If I now do what I do not want, I agree with the Law [and recognize] that it is good” (v. 16). That is all, but that is what should be proven.

Unfortunately — or fortunately — Paul happened to express this supporting argument so well that what to him and his contemporaries was a common sense observation appeared to later interpreters to be a most penetrating insight into the nature of man and into the nature of sin. This could happen easily once the problem about the nature and intention of God’s Law was not any more as relevant a problem in the sense in which Paul grappled with it. The question about the Law became the incidental framework around the golden truth of Pauline anthropology. This is what happens when one approaches Paul with the Western question of an introspective conscience. This Western interpretation reaches its climax when it appears that even, or especially, the will of man is the center of depravation. And yet, in Rom. 7 Paul had said about that will: “The will (to do the good) is there . .” (v. I8).

What we have called the Western interpretation has left its mark even in the field of textual reconstruction in this chapter in Romans. In Moffatt’s translation of the New Testament the climax of the whole argument about the Law (v. 2 5b, see above) is placed before the words “wretched man that I am . . .” Such a rearrangement — without any basis in the manuscripts 20 — wants to make this exclamation the dramatic climax of the whole chapter, so that it is quite clear to the reader that Paul here gives the answer to the great problem of human existence. But by such arrangements the structure of Paul’s argumentation is destroyed. What was a digression is elevated to the main factor. It should not be denied that Paul is deeply aware of the precarious situation of man in this world, where even the holy Law of God does not help – it actually leads to death. Hence his outburst. But there is no indication that this awareness is related to a subjective conscience struggle. If that were the case, he would have spoken of the “body of sin,” but he says “body of death” (v. 25; cf. I Cor. 15:56). What dominates this chapter is a theological concern and the awareness that there is a positive solution available here and now by the Holy Spirit about which he speaks in ch. 8. We should not read a trembling and introspective conscience into a text which is so anxious to put the blame on Sin, and that in such a way that not only the Law but the will and mind of man are declared good and are found to be on the side of God.

Stendahl, K. (1963) “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West” in The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 199-215

Thompson, J.W. (2014) The Church According to Paul: Rediscovering the Community Conformed to Christ, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Every church father is a potential Mortimer Snerd.

Very interesting. I have long felt that the doctrine of natural corruption by original sin was one of the most harmful doctrines of Christianity.

This is a gloss of the fact that Christian salvation lacks objective substance. It’s entire history is desperate reification of the magical property of being saved. Something that Buddhism for example doesn’t feel a need to reach for.

“The Revised Standard Version is more accurate with

‘So that the law was our custodian until Christ came.'”

Funny; the NRSV has “disciplinarian”. Backsliding?

BTW, that long Thompson quote’s kinda broken toward the end.

Here in full is the last section of that quote that I truncated in the main post:

Thanks; but I was referring to the last paragraph repeating the one before it.

Thsnks. Appears I did a copy and paste instead of a cut and paste. I really do have to learn to read my own posts before anyone else does.

I’ve long thought that Augustine was the Antichrist.