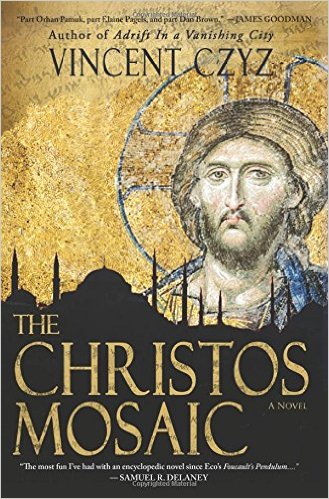

A new book arguing a mythicist case has been published. If you like your serious intellectual pursuits spiced with vicarious adventure then Vincent Czyz (a winner of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction) has written for you a novel that weaves its plot around protagonists gradually discovering Jesus was less a historical figure than a mosaic of facets of many ancient figures, both mythical and historical. As you can see from the side image we are talking about The Christos Mosaic. One reviewer describes it “a serious tome, which prompts readers to think“, a “scholarly novel that required serious research“.

Earl Doherty appears to have had a similar project in mind when he wrote a novel titled The Jesus Puzzle: A Novel About the Greatest Question of Our Time to complement his formal scholarly arguments. I enjoyed Doherty’s novel because it hit on the main points of his argument in easy to digest doses against dramatic backdrops and in that way producing a true “teach and delight” experience. Czyz’s novel is more action-packed than Doherty’s. It’s a mystery thriller set in the world of the black market for antiquities, peppered with a little sex and a little more violence, with the narrative ebbing and flowing through the main character’s discovery that the Jesus figure evolved as a mosaic of diverse religious ideas, motifs and persons.

Another “Christ Myth” novel that I read was Vardis Fisher’s Jesus Came Again: A Parable. That was first published sixty years ago but getting it published caused the author all sorts of grief back then. Fisher created his own version of the gospel but wrote it as a modern version of how the first gospel appeared to be written: as a parable, not as history or biography.

Perhaps novels like these are “mythicist” answers to apologist authors writing novels about encounters with Jesus or personal takes on what Jesus was like.

Vincent Czyz’s novel contains a “cast of historical characters” in the opening pages to prepare the reader for what is to come. The cast includes names like Judas the Galilean, Philo, Josephus, Simon Bar Giora, Ebionites, Papias, and Father Roland de Vaux. The entry for the last mentioned is:

Director of the Ecole Biblique et Archaeologique, a Dominican school based in Jerusalem. Deeply conservative, both religiously and politically as well as reputedly anti-Semitic, he grew up in France and ultimately led the international team that studied a trove of Dead Sea Scrolls and scroll fragments found in Cave 4 in 1952.

This is followed by a historical timeline listing events from 198 BCE (Judea coming under the control of the Seleucids) through to 95-120 CE (the composition of the Gospel of John).

Readers familiar with this topic will be particularly interested in Czyz’s Afterword. It is titled: Mythicists and Historicists. A couple of excerpts:

Clearly the idea that Jesus never existed isn’t new. What is new is that the idea is gaining currency. . . .

If you read Ehrman’s book without the benefit of having made some sort of in-depth study — formal or otherwise — of the Bible, or if you fail to give equal attention to the counterarguments of those who have, Ehrman’s case seems persuasive. It is rather convincingly refuted, however, in Bart Ehrman and the Quest of the Historical Jesus . . . . In this collection of essays, Frank Zindler, Richard Carrier, and Earl Doherty, among others, take Ehrman thoroughly to task, highlighting some rather unscholarly mistakes and some that are downright embarrassing.

Czyz describes the reading that led him to question the historicity of Jesus, his critical engagement with both mythicist works and mainstream works (e.g. Burkert, Koester) on ancient religions, mythology and the Christian gospels. Robert Price and Earl Doherty are singled out for special influence on his thinking.

The intellectual exploration of the novel takes us through not just Q but the hypothetical earliest layers of Q, Q1 and Q2, the Logos, Philo’s heavenly Adam, Wisdom Sayings, Cynic philosophy, the Therapeutae, the Gospel of Thomas, Mystery cults, Josephus and key figures in the Jewish War, Greco-Roman deities, the Bacchae, and many more.

Finally towards the end we read how the various parts of the mosaic were coming together in the mind of the inquisitive Drew:

But after the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD and the reestablishment of Roman hegemony, Mark sees the futility of a military messiah and cobbles together a spiritual redeemer . . . from pieces of other religious leaders, pagan magicians, messianic figures, and Paul’s letters. Why else does Christ talk sometimes like a Cynic, sometimes like John the Baptist, sometimes like a Zealot, sometimes like James the Just?

Mark’s gospel was not a deliberate deception. It was part of a tradition. It was midrash — religious fiction. Allegory. Entirely acceptable at the time. Wasn’t Serapis a composite god? Weren’t the rites of Mithras grafted onto the Saturnalia? Even the Qumran community did the same thing in its own way: past scriptures were interpreted as though they applied to the first century AD. . . .

After acknowledging Frank Zindler’s hope that he will see in his lifetime “the recognition that Jesus of Nazareth is as much a mythical figure as Osiris or Dionysus”, Vincent Czyz professes to be “somewhat less ambitious”:

I hope this novel will lead readers to do their own research . . . and perhaps heed Emerson’s exhortation to establish “an original relation to the universe.” . . . It is time to stop looking outside ourselves for a savior and start doing work on our own.

I must confess that the intellectual play interested me more than its fictional stage setting. But that’s probably just me. I have not taken up fiction reading in a serious way for a long time now; non-fiction dominates my personal craving at the moment. There may be an occasional detail in the novel that some readers would find problematic, but that’s the case with most serious arguments that we read. Those details do not sidetrack us from appreciating the main journey and fresh insights into old information.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I have read rapidly the book, where the ”rapidly” is justified by the same your feeling:

I must confess that the intellectual play interested me more than its fictional stage setting. But that’s probably just me.

I see interesting good findings in:

1) the impersonality of the use of ”Jesus” in Paul:

2) why the myth of the veracity of a historical Jesus is so rooted:

But I should criticize the continue (”conspirazionist”, I would say) insistence on James as an anti-pauline hero, almost that the author should feel compelled to criticize Paul for ”something”. If there was a historical Jesus – as the logic goes – the ”moral” fault of Paul has to be clearly the one of having deliberately concealed him (or, as Nietzsche said, Paul crucified Jesus to his cross: the same anti-Christian accusation by Muslims). But being absent an historical Jesus, I see almost a general ”fashion” to accuse Paul of having concealed not a historical Jesus, but a historical James in his place, to the point of assuming radical hypothesis as that Paul had ”murdered” James (or that Paul was the Liar mentioned by the Essenes).

Agreed that Paul was in ideological conflict with James the Pillar. But the title ”the Just” is probably a late invention.

I know many people who are historicists only because they ”hate” Paul. They do not trust him. They believe that Paul is hiding them something deliberately. ”Therefore” Jesus existed.

But from a pure mythicist view, Paul can be blamed only for having insisted to have hallucinations that he possibly didn’t have actually (in order to persuade the Galatians). Not more than that.

Yes, the reconstruction proposed in the novel is one of several possibilities, and as deserving of serious consideration and engagement as other proposals. I found it to be an interesting contribution to the discussion. I am surprised it has not been picked up by more people with an interest in this question.

Thanks for the review/update! I’ve been wondering for a while if we’ll ever get the mythicist answer to “The Da Vinci code” (just hopefully a lot smarter and better written) and now it seems that this day had come.

It would be interesting to compare the public reaction to this book to that of “Da Vinci code”, a book which was all about Jesus historicity on steroids.

I’m really looking forward to reading this book, more so because the author actually mentioned Ehrman, Zindler, Price, Doherty and Carrier.

Deeply gratifying to see intelligent discussion of The Christos Mosaic among attentive and knowledgeable readers!

I think the “Jesus Mythicism” hypothesis (that Jesus never existed) posits too high a Christology (Jesus as a dying/rising God) to interpret the Jesus of our oldest sources.

For instance, a very early source about Jesus preserved in one of the speeches in Acts says:

“Jesus the Nazarene, a man attested to you by God through miracles and wonders and signs THAT GOD DID THROUGH HIM … (Acts 2:22-24).”

So, it is not thought here that Jesus was an all powerful God doing miraculous things on earth, but rather that Jesus was a man THROUGH WHOM God was doing miracles That God, not Jesus, was the source of Jesus’ power is evident in the gospel of Mark where Mark has Jesus identify himself as a fallible human prophet who can’t perform miracles in his hometown (Mark 6:4-5). If Jesus had the powers of a God he would have been able to perform miracles in his hometown.

Many things also speak against interpreting Jesus as a “high Christology” divine figure resolutely going forth on a suicide mission to atone for the sins of the world (and expecting a speedy resurrection). Rather, Jesus is terrified of dying, as demonstrated by his desperate prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane (Mark 14:32-42). This is even clearer when Jesus is on the cross, desperately questioning God as to why He has abandoned Jesus and begging for Elijah to miraculously come and save him from the cross (Mark 15:34-36). This is not a “God Incarnate” resolutely fulfilling his mission. The letter of the Hebrews also preserves the tradition that Jesus was frantically trying to get out of dying. Hebrews suggests Jesus offered up prayers and loud cries and tears to be saved from death (Hebrews 5:7)

Take as extreme case the god Mithra. He is the only of the Hellenistic gods that does not die (and even less rises), yet he is not so much high as a god when he undergoes the titanic effort/i> to kill the bull. Surely he was portrayed as extremely suffering in the process.

Ehrman and other biblical scholars who know better are failing their public readers when they use the Acts passages to “prove” the earliest Christology was a low one.

In fact they are telling readers to submit to their own authority and are hiding from them the fact that there is debate among their peers about the meaning of those passages.

There is simply no evidence at all that indicates the Acts passage is based on a very early tradition. None. They are merely asserting that because it suits their case against mythicists to do so, and they know the public will on the whole defer to their authority.

The claim that the Acts passage is based on earlier tradition is entirely speculative. It is derived from the hypothesis that the earliest Christology was a low one. In other words, the claim is not evidence for an early low christology but a conclusion based on circular reasoning.

The evidence we do have is that Acts was unknown in the wider world until the mid second century. That’s when it first appears in the external record. The evidence tells us that this was at a time of the Marcionite controversy. The internal and external evidence together strongly suggest Acts was written or at least heavily redacted as an anti-Marcionite document.

The evidence we have points to those passages in Acts used by Ehrman to support a very early tradition are actually late inventions to counter the Marcionite “heresy”.

I am not saying the evidence I have alluded to here is proof of that claim, but it does strongly suggest it.

What is misleading is when Ehrman and co simply tell you one side of the story, a side that has nothing more than circular reasoning and their own authority and their decision not to tell readers what other peers of theirs say.

There is a growing body of scholarship actually that argues that the earliest Christology was in fact very high and the low christology was a later evolution. But again, some of the main sources for this view are apologists so one once again sees a personal bias quite possibly at work.

Beware any scholar who writes dogmatically and writes as if he or she represents what the rest of his or her peers believe.

Acts was a work to bring the Pauline theology and the synoptic theology together, and to reify Christ Jesus as a human.

Portraying Jesus as being terrified of dying was part of the shtick.

“Acts was a work to bring the Pauline theology and the synoptic theology together …” I agree with you on that.

“The letter of the Hebrews also preserves the tradition that Jesus was frantically trying to get out of dying. Hebrews suggests Jesus offered up prayers and loud cries and tears to be saved from death (Hebrews 5:7)”

As has been pointed out by Carrier and others, the cries and tears can happen in places that are more perfect copies of places down here. The upper firmament were the Moon orbits was host to gardens and palaces and so forth.The book of Hebrews in fact points out that Jesus sacrificing action was in the more perfect copy temple in the heavens, not the one in Jerusalem in 1 century.

So, it is not thought here that Jesus was an all powerful God doing miraculous things on earth, but rather that Jesus was a man THROUGH WHOM God was doing miracles

If Paul had in mind this all the times he talks about the great actions of God by mean of Jesus (for example: Romans 3:21-25), then why didn’t he take advantage (to exalt even more God behind Jesus) by showing in what consisted, by direct contrast to absolute God’s power, the ”poverty” of Jesus (in living a life like our, and not only a death like that of the human beings) ?

The ”poverty” he assumes for Jesus seems to be one of the same kind of poverty to which the ”archons of this eon” are destined (”who are coming to nothing”: 1 Cor 2:6, “those weak and miserable forces”: Gal 4:9), once defeated in the next future: a ”poverty” regarding only the death and destruction, not an entire life of sufference.

God cannot become more great only because there is complete silence about the poor and humble life of his Son. But God can become more great because there is total emphasis on the death of the his Son.