We have covered the subject of the apostle Paul’s silence on Jesus’ life many times on Vridar. But for quite a while now, I’ve been thinking we keep asking the same, misdirected questions. NT scholars have kept us focused on the narrow confines of the debate they want to have. But there are other questions that we need to ask.

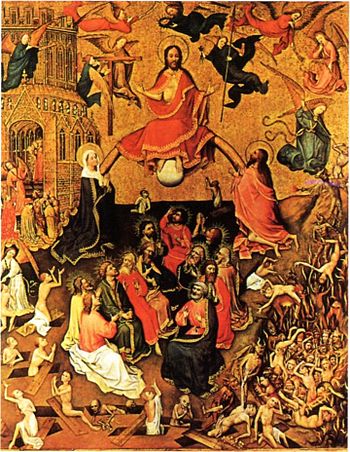

Pretty apocalyptic prophets, all in a row

For example, Bart Ehrman, defending his claim that Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet, has habitually argued that we can draw a sort of “line of succession” from John the Baptist, through Jesus, to Paul. In Did Jesus Exist? he explains it all in an apocalyptic nutshell:

At the beginning of Jesus’s ministry he associated with an apocalyptic prophet, John; in the aftermath of his ministry there sprang up apocalyptic communities. What connects this beginning and this end? Or put otherwise, what is the link between John the Baptist and Paul? It is the historical Jesus. Jesus’s public ministry occurs between the beginning and the end. Now if the beginning is apocalyptic and the end is apocalyptic, what about the middle? It almost certainly had to be apocalyptic as well. To explain this beginning and this end, we have to think that Jesus himself was an apocalypticist. (Ehrman, 2012, p. 304, emphasis mine)

Dr. Ehrman sees the evidence at the ends as “keys to the middle.” For him, it’s a decisive argument.

The only plausible explanation for the connection between an apocalyptic beginning and an apocalyptic end is an apocalyptic middle. Jesus, during his public ministry, must have proclaimed an apocalyptic message.

I think this is a powerful argument for Jesus being an apocalypticist. It is especially persuasive in combination with the fact, which we have already seen, that apocalyptic teachings of Jesus are found throughout our earliest sources, multiply attested by independent witnesses. (Ehrman, 2012, p. 304, emphasis mine)

You’ve probably heard Ehrman make this argument elsewhere. He’s nothing if not a conscientious recycler. Here, he follows up by summarizing Jesus’ supposed apocalyptic proclamation. Jesus heralds the coming kingdom of God; he refers to himself as the Son of Man; he warns of the imminent day of judgment. And how should people prepare for the wrath that is to come?

We saw in Jesus’s earliest recorded words that his followers were to “repent” in light of the coming kingdom. This meant that, in particular, they were to change their ways and begin doing what God wanted them to do. As a good Jewish teacher, Jesus was completely unambiguous about how one knows what God wants people to do. It is spelled out in the Torah. (Ehrman, 2012, p. 309)

Unasked questions

However, Ehrman’s argument works only if we continue to read the texts with appropriate tunnel vision and maintain discipline by not asking uncomfortable questions. Ehrman wants us to ask, “Was Paul an apocalypticist?” To which we must answer, “Yes,” and be done with it.

But I have more questions.

- Why does Paul argue inferentially that Christ’s resurrection indicates the end of the age, when he could have fallen back on Jesus’ basic teaching?

- Why is Paul’s gospel so different from Jesus’ gospel as presented in the synoptic gospels?

- It seems obvious that Paul thought of himself as an apocalyptic prophet. But did Paul think that Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet? What role or roles did Paul think Jesus played?

- If Jesus’ core message was about the coming kingdom of God, the Son of Man, the coming judgment, the need for repentance, and God’s forgiveness, why are these themes largely missing from Paul’s message?

These questions become all the more vexing when we pause to consider that if Paul had referred to Jesus’ gospel, it would likely have strengthened his message. He need not have quoted Jesus verbatim. He could simply have noted that Jesus proclaimed the coming kingdom, that he prophesied his own death and resurrection, that he predicted the coming judgment, and that he urged sinners to repent and be forgiven. But he didn’t, and we’re left to wonder why.

How did Paul remember Jesus?

Georgia Masters Keightley, in her essay entitled “Christian Collective Memory and Paul’s Knowledge of Jesus” (in Memory, Tradition, And Text), seeks to discover what Paul knew about Jesus and how he knew it. The emphasis on “how” is important for Keightley, because she wants to de-emphasize the factual, text-centric knowledge of the written gospels and focus instead on the personal knowledge believers in Christ receive via rituals and commemoration.

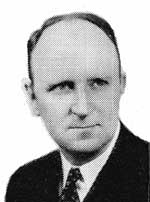

1900-1990

Keightley praises John Knox (the 20th century scholar, not the 16th century Scottish minister), who talked about Paul’s “knowing” Jesus on a personal level. She writes:

Despite the fact that absent factual data the remembrance of Jesus would be poorer, it is not to be concluded that memory is merely an aggregate of scattered oral traditions. To the contrary, memory conveys how the community felt about Jesus, how it experienced him. It is a knowing of Jesus that goes beyond the picture of him that derives from documentary sources. According to Knox, memory has to do with the apprehension of the quality and character of Jesus’ person, the quality and character of his relation to his friends and followers. . . .

Without developing his insight further, Knox concludes that Christian worship practices are a likely means by which the collective memory of Jesus has been mediated throughout the generations. (Keightley, 2005, p. 131, emphasis mine)

Knox believed that Paul and other early Christians knew and remembered Jesus on an emotional, visceral level, and Keightley claims that modern social theory supports his contention. She argues “that collective memory is literally embodied in human bodies and is preserved, mediated in and through ritual performance.” Her larger goal is to expand the discussion, showing “that a broader, more interdisciplinary approach to study of the New Testament presents the possibility of rich new understandings of this material.” (Keightley, 2005, p. 132)

Unfortunately, Keightley helps perpetuate the myth that Maurice Halbwachs understood social memory as depending on actual places in time and space when she writes:

While we situate our personal reminiscences within what appears to be the conceptual/abstract past, the truth is this past always has as its reference the actual material space(s) the group occupies. (Keightley, 2005, p. 133, emphasis mine)

I refer you back to the previous post on Rituals and Remembrance, in which we explained that Halbwachs’s broader concept of localization has two fundamental components: (1) the placement of individuals within the perspective of a group and (2) the placement of individual memories within the larger framework of group memories.

A Freudian detour

Keightley tells us that Halbwachs demonstrated how early Christians superimposed their memories of the Holy Land over existing Jewish locations. But she also points out that the dimension of time also plays a role in fixing memories within known frameworks.

In respect to time, personal reminiscence too must be fitted to the group’s schema. For the Christian, time is appropriated on the basis of the yearly celebration of those events leading up to—and subsequent to—Holy Week. Thus, as Halbwachs argues, memory is not just the simple recall of facts; to the contrary, it involves the construction of an appropriate narrative scheme in which to locate our personal data [Connerton: 26] (Keightley, 2005, p. 134, emphasis mine).

I have no idea why Keightley appears to be quoting Halbwachs, but then cites Paul Connerton. She seems to be referring to this observation from Connerton’s landmark work, How Societies Remember:

To remember, then, is precisely not to recall events as isolated; it is to become capable of forming meaningful narrative sequences. In the name of a particular narrative commitment, an attempt is being made to integrate isolated or alien phenomena into a single unified process. This is the sense in which psychoanalysis sets itself the task of reconstituting individual life histories. (Connerton, 1989, p. 26, emphasis mine)

In this context, Connerton is discussing Freud’s recommendation that analysts “direct attention to the past when the analysand insists upon the present, and to look for present material when the analysand dwells on the past.” (Connerton, 1989, p. 26) The analyst attempts to break through the patient’s bubble, to dismantle the unhealthy construct that depends upon a “particular kind of narrative discontinuity.”

This discussion has only the merest tangential relationship to the normal process of fitting one’s personal narrative into a group schema. It focuses on dysfunctional behavior, and strategies for rebuilding a person’s true narrative history, as we can see from the title of Freud’s essay, “Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through.” The key is to work through the narrative discontinuity the analysand has constructed.

The point of this narrative discontinuity is to block out parts of a personal past and, thereby, not only of a personal past, but also of significant features of present actions. In order to discard this radical discontinuity, psychoanalysis works in a temporal circle: analyst and analysand work backwards from what is told about the autobiographical present in order to reconstruct a coherent account of the past; while, at the same time, they work forwards from various tellings about the autobiographical past in order to reconstitute that account of the present which it is sought to understand and explain. (Connerton, 1989, p. 26, emphasis mine)

Distortion arising from mental sets

Speaking of narrative frameworks, Connerton raises some significant issues with respect to the way we perceive, re-package, re-categorize, and re-structure our memories. The very act of retelling a memory as a story imposes an artificial structure, one shaped by the expectations of our society and informed by our culture and family group. Oral historians, unless they take great care, will inadvertently mold the stories of the people they interview.

For some time now a generation of mainly socialist historians have seen in the practice of oral history the possibility of rescuing from silence the history and culture of subordinate groups. Oral histories seek to give voice to what would otherwise remain voiceless even if not traceless, by reconstituting the life histories of individuals. But to think the concept of a life history is already to come to the matter with a mental set, and so it sometimes happens that the line of questioning adopted by oral historians impedes the realisation of their intentions. (Connerton, 1989, p. 18-19, emphasis mine)

Our mental sets invite embellishment, a situation further aggravated by our desire to please an audience. When we choose to recall a memory and share it with someone else, we package it, consciously or not, into a beginning, a middle, and an end. We form connections where none existed. We try make it relevant to current circumstances. And we’re so accustomed to these frames (our “mental set”), that we struggle to recognize them as external to the memory itself.

Connerton notes that during conversations with oral historians, interviewees will sometimes pause and say they have nothing more to tell, and he warns:

The historian will only exacerbate the difficulty if the interviewee is encouraged to embark on a form of chronological narrative. For this imports into the material a type of narrative shape, and with that a pattern of remembering, that is alien to that material. In suggesting this the interviewer is unconsciously adjusting the life history of the interviewee to a preconceived and alien model. That model has its origin in the culture of the ruling group; it derives from the practice of more or less famous citizens who write memoirs towards the end of their lives. (Connerton, 1989, p. 19, emphasis mine)

I have no serious objection with Keightley’s observations that, following Halbwachs and Connerton, memory depends on social frames in order for us to make sense of them. In fact in this section she makes three important and related points:

- “[M]emory’s framework provides the community’s overarching view of reality; it sets forth reality’s fundamental order, character, and significance.”

- Our individual memories “are in reality but one limited point of view on the collective experience. Furthermore, these points of view change as we change social locations or shift social locations within the different groups to which we belong.”

- Our combined collective memories create groups. “Groups come into existence precisely because their members hold shared experiences. Because certain of these are deemed significant, they are held to be both formative and normative and give rise to a unique set of meanings and values.” (Keightley, 2005, p. 134, emphasis and numbering mine)

But we must not lose sight of the fact that the frameworks we depend on to provide meaning and coherence also, by their very nature, distort reality. In some cases, they induce forgetfulness in that some recollections simply do not fit within the permitted limits of our frameworks. Keightley, again following Halbwachs, describes a kind of forgetting that happens when “we lose touch with the group to whom certain memories belong and for whom such remembrances matter.” (Keightley, 2005, p. 134)

I would, however, ask you to consider another kind of abrupt forgetfulness or at the very least, radical reinterpretation, that occurs when individuals face cognitive dissonance. In these cases, our original recollections may be replaced by fictitious memories — inventions that fit better with our expectations, desires, and needs. Hence, social memory’s constraints more than just “refract” individual memory (to use Anthony Le Donne’s term); they may erase it entirely and put something more palatable in its place. As an example, see part 2 in this series, “A Case Study at Ellis Island.”

“This do in remembrance of me”

We have strayed from Keightley’s main point, which is to champion Knox’s position that the Apostle Paul remembered Jesus through rituals and what Connerton called “bodily practices.” Nor is Knox the only scholar to have suggested as much. She quotes extensively from Margaret MacDonald’s “Ritual in the Pauline Churches” (found in Social Scientific Approaches to New Testament Interpretation by David G. Horrell, available now at Amazon for only $675).

If Hengel is correct that Paul’s basic insights about Jesus Christ were formed early on, Margaret MacDonald finds their source in Paul’s participation in Christian worship. She argues that “the Pauline correspondence itself grows out of and is rooted in, what is experienced in the midst of ritual” (237; also Hurtado: 42). Ritual was so crucial for the first Christians, she says, because it was here “that individuals discovered for the first time, or renewed their acceptance of, the authority that transformed their experience” (237). In other words, it was preeminently during ritual performance that Pauline Christians met firsthand—and came to know personally, existentially—the veritable meaning of the lordship of Christ. (Keightley, 2005, p. 134, emphasis mine)

This understanding of the mindset of believers during the spread of Christianity in its formative decades would explain Paul’s apparent ignorance of what Jesus said and did during his time on earth. Early Christian converts, including Paul himself, were far more interested in knowing Christ through the rites of baptism, the Eucharist, and other rituals of worship. Keightley tells us that Knox first expounded this idea decades before the memory boom in modern NT studies.

To the end of his life, John Knox continued to express dismay that his biblical scholar colleagues were unable to see what his careful scrutiny of the New Testament literature brought him to see so clearly: that the Christian community bears at its heart a living and abiding memory of Jesus the Christ. In retrospect, Knox’s inability here can be attributed to the lack of theoretical tools he had at his disposal to explain how or why the Christian community has the power of memory—how memory comes to be transmitted through the generations. (Keightley, 2005, p. 150)

We should take Knox’s thesis seriously, while realizing that is raises as many questions as it claims to answer. For example, it would appear that Paul knew Christ in almost the same way that a Christian of 400 CE, 1500 CE, or even of today would know him — namely through the repetition of rituals and religious bodily practices such as the singing of hymns, the recitation of a creed, or by saying the Lord’s Prayer. If he was correct, then what are the implications for the quest of the historical Jesus?

The stark differences between Paul’s and Jesus’ gospels

We should also note that John Knox recognized Paul’s apparent ignorance of Jesus’ teaching, which ran more deeply than most modern scholars would care to admit. He marveled at Paul’s “disregard of what is undoubtedly the most characteristic, constant and pervasive feature of Jesus’ own teaching.” (Knox, 2000, p. 119) Specifically, Mark tells us that Jesus started his ministry, calling to people to repent, be forgiven, and ready themselves for the coming Kingdom of God. Yet Paul avoids the words forgiveness and repentance throughout his letters.

It may at first seem strange and arbitrary to ascribe such great importance to forgiveness in the experience of Paul, in view of the fact that he so seldom uses the term. Indeed, it is not altogether clear or sure that he uses the noun at all. It occurs once in Ephesians (1:7), which Paul almost certainly did not write, once in Colossians (1:14), which is the most dubious of the other letters, and nowhere else in the Pauline epistles. (Knox, 2000, p. 118)

It’s rather clear, then, that Paul never used the noun “forgiveness.” Why would he would avoid one of the central features of Jesus’ gospel?

As for the verb forgive, Paul employs it several times in 2 Corinthians and in Col. 3:13 (χαρίζεσθαί [charizesthai]) in discussing how we shall deal with others. But only twice in all his letters does he speak of God as “forgiving” us; and of these, one instance occurs in Colossians (2:13 — again (χαρίζεσθαί [charizesthai] [1]) and the other in a quotation from the Old Testament in Rom. 4:7 (ἀφεῖναι (apheinai) [2]). (Knox, 2000, p. 118, bold emphasis mine)

[1] actually: χαρισάμενος (charisamenos)

[2] actually: ἀφέθησαν (aphethēsan)

We have every right to be surprised at these omissions.

The absence of any emphasis whatever in Paul’s letters upon these two concepts is much more than interesting or even curious — it is nothing short of astounding. (Knox, 2000, p. 118, emphasis mine)

Knox eventually argues for the importance of repentance and forgiveness in Paul’s theology even though Paul does not use the terms. He focuses instead on Paul’s soteriological emphasis on “grace,” which Knox thinks leads to an implied tradition of forgiveness. Yet these are not the only missing features from Jesus’ gospel as we find it in the Synoptics. Where, for instance, is the coming Kingdom? As Knox understood it, for Paul that kingdom was already here on earth.

To be “in Christ” was to be an organic part of the new creation, of which the risen Christ was the supreme manifestation and the effective symbol; it was, indeed, to belong to the eschatological kingdom of God that had already appeared within history as the church. (Knox, 2000, p. 115, emphasis mine)

Knox realized that such an assertion conflicts with the notion that the Kingdom would arrive along with the final judgment and the end of this age.

Paul does not discuss the question, later to be debated, of the relation of the church to the kingdom of God, but he might have said something like this: In complete actuality the church is most certainly not the kingdom of God; it belongs to history, suffers from all the vicissitudes of historical existence, and shares in all the limitations and sins that are our natural lot: but in inner principle it is the kingdom, for the source of its distinctive character is its actual participation in the event toward which all creation has been moving. The church is the church because it belongs, not to this age, but to the age that is to come and in Christ has already begun to be. The church, in the truest and most authentic sense, is the kingdom of God insofar as that kingdom has been able to find room within the present world. (Knox, 2000, p. 115, bold emphasis mine)

Knox’s apologetics

In the end, Knox must explain away these problems with Paul’s gospel. He ties together threads of the doctrine of grace to the concepts of forgiveness, repentance, and reconciliation with strained arguments that meander for page after page. What he cannot prove with reason, he asserts with passion:

Paul, who without ever having listened to his words was yet his greatest disciple, is wanting to say just what Jesus was constantly saying — that any peace with God we can have must consist not in the awareness of being deserving, but in the assurance of being forgiven; not in the consciousness of being good enough to be loved, but in the knowledge that Another is good enough to love us. (Knox, 2000, p. 124-125, emphasis mine)

But he goes too far. He not only explains Paul’s theology, but argues for its correctness, its truth.

As apostle he carried the gospel across half the ancient world and, almost single-handed, laid the foundations of Gentile Christianity; as interpreter he set the lines Christian theology was to follow, through Mark, to John, and beyond; and at many points he spoke himself what has proved to be the final word. The marks of human frailty can be discerned in his work, but to the really discerning they serve only to make more clear the supreme greatness of his achievement — or rather the supreme greatness of what God wrought through him. (Knox, 2000, p. 131, emphasis mine)

The unsuspecting reader might find Knox’s preaching at the end of Chapters in a Life of Paul somewhat disconcerting. Still, the work has much to recommend it. I think he’s absolutely correct in distrusting the chronology of Acts not only when it conflicts with Paul’s epistles, but in nearly every case wherein it purports to depict Paul’s life. Attempts to harmonize Paul’s first-person letters with Luke’s later, secondhand accounts will prove fruitless.

However, his slow change from learned scholar to unwelcome proselytizer reminds me of an acquaintance who seems cheerful and friendly at first, until it slowly dawns on you that he’s trying to get you involved in selling Amway.

Conclusion

John the Baptist’s message and Jesus’ gospel in the first three canonical gospels are distinctly similar. John demanded the crowd come forth and be baptized in the Jordan, a bodily practice that signified a person’s repentance, a deliberate act intended to bring about the forgiveness of sins. Similarly, Jesus followed on where John had left off:

Now after John had been taken into custody, Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel of God, and saying, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel.”

(Mark 1:14-15, NASB)

On the other hand, while we may well call Paul an apocalypticist, we have to tie ourselves into rhetorical knots in order to explain how his message could have diverged so greatly from Jesus’ gospel in such a short time. Why would Paul reject or ignore the teachings of the disciples who supposedly knew and learned from the greatest teacher who ever lived?

Further, if Knox is correct about Paul’s knowledge of Jesus coming by way of religious rituals, essentially the same rituals all Christians have participated in and continue to take part in today, then he adds nothing to our understanding of the historical Jesus. For Paul and his churches, Jesus’ only memorable acts were his institution of the Eucharist (unless the tradition in 1 Corinthians 11 is an interpolation), his death, and his resurrection. Even if Paul was sharing in a social memory of Jesus, it was not a memory of what he said but a memory of who he was (and is!) and how his atoning death saved believers from sin and damnation.

Keightley concludes “this new methodology opens exciting new possibilities for knowing, apprehending the Christ that Paul knew so intimately and so well!” [exclamation point hers] On the contrary, with respect to the historical Jesus, I think it pulls the curtain over the Pauline era. It says Paul knew the risen Christ intimately, and almost nothing else. In fact, it reinforces what Paul already wrote:

For I determined not to know any thing among you, save Jesus Christ, and him crucified.

(1 Cor. 2.2, KJV)

Connerton, Paul

How Societies Remember (Themes in the Social Sciences), Cambridge University Press, 1989

Ehrman, Bart

Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth, HarperOne, 2012

Keightley, Georgia

“Christian Collective Memory and Paul’s Knowledge of Jesus” in Kirk & Thatcher, Memory, Tradition, and Text: Uses of the Past in Early Christianity, SBL, 2005

Knox, John

Chapters in a Life of Paul, Mercer University Press, 2000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

SO many good questions asked here, Tim! Well done!

-Dave Fitzgerald

Did n’t have time to read but as already going thro M Mavens will meet it soon enough.

This is a courtesy posting as I must visit Vridar at least once in the day.

The only plausible explanation for the connection between an apocalyptic beginning and an apocalyptic end is an apocalyptic middle. Jesus, during his public ministry, must have proclaimed an apocalyptic message.

Uh… no. Ohio is described in a (Great Lakes) midwestern riddle as “What’s round at the ends and high in the middle?” So even if the ends are apocalyptic (4 BCE – 6 CE and 64 – 73 CE) the middle need not be.

And Josephus probably never mentioned Jesus.

I think Ehrman so accustomed to his own little echo chamber that it never dawns on him to question it.

Would participation in the ritual of a sacred meal normally give rise to a “mystical” experience unless it contains some psychoactive substance? Could commemoration of the “Last Supper”/”Eucharist” have given rise to “resurrection visions”? Do we have any relevant clues in I Corinthians 10.14 & 11.29 and 2 Corinthians 3.6?

I’m not convinced there’s much “there” there, when it comes to psychoactive substances in the first century CE. I think the standard practices, like fasting and prayer (with lots of repetitive motion and utterances) are enough to do the trick.

Please understand that I don’t think it’s impossible; I just think it isn’t necessary.

Probably right. Obviously hallucinations occur without drugs. But see e.g. Clark Heinrich, “Magic Mushrooms in Religion and Alchemy” (2002). The author of “Revelation” swallows the scroll and is in spirit on the Lord’s Day.

Tim, wonderful exposition. Thank you very much, this is one of the most interesting and glossed over aspects of nascent Christianity.

I note that you last quote from Corinthians suggests that Paul didn’t even know the risen Christ even, just the crucified one.

Interesting point. Thanks for reading Vridar.

What Andrew Lucas said!

Indeed, Paul by all accounts did not know or meet the historical Jesus. Therefore by any account, he mostly knew the Christ of faith. Or fallible memory, or ritual, or projected desires.

Or, his own fantasy.

Not by “all” accounts. See Johannes Weiss, Paul Feine, Joseph Klausner, Willem van Unnik, Stanley Porter, &c. The idea that Paul knew about, and was hostile towards Jesus before his execution, is quite consistent with Galatians, 2 Corinthians and Philippians, as well Acts. This will be ruled out, of course, by those who believe that Jesus never existed at all, and especially by anyone who dismisses any ostensible historical detail in first century church literature as “at best, absurd rubbish”.

Paul meeting Jesus live and in person, prior to his resurrection, seems ruled out, mainly.

Here is a link to a new article from Niels Peter Lemche that discusses social memory: http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/2015/04/lem398021.shtml

Thanks, Scot.

The apocalypse is overrated and sensationalistic anyway. In my reading, it just meant that the local Lord reviews you every year, to see if you paid your tax or “sacrifice to the Lord.”

Nonpayment to be sure, incurs severe penalty. One “day.”

Generally Paul in his own base set of letters doesnt need to deal with an historical Jesus. However, if we were to factor in the Marcionite and Gnostic idea that the Apostle also wrote THE Gospel, he’d at least have to write up an allegory. That still would not need an historical Jesus. If he wanted to drop clues his Jesus was merely an allegory, we could posit such clues would be something like a Mary Magdalene wandering around on the resurrection Sunday in pre-dawn dark and stumbling into Lazarus’ tomb by mistake and setting off a chain of errors where Peter and John get mistaken for angels.

Small wonder they had three levels of believer in Gnostic and Marcionite Christian churches. The most basic believers didnt get the joke.

Still didnt need an ounce of real history.