I’ve been trying to think of something worthy of posting on this Easter Sunday, 2015. All I can come up with at the moment is a subject I’ve had on the back burner for some time, namely the handful of references in the Fourth Gospel (FG) that remind us of Asclepius. Longtime readers may recall Neil’s description from his review of Jesus Potter Harry Christ.

Asclepius the gentle and personally accessible deity, lover of children, gentle, exorcist and healer, and one whose cult was considered at certain times the greatest threat to Christianity.

Several scholars have remarked upon the parallels in terminology and legends that surround both Jesus and Asclepius. Of course, the most obvious things that come to mind would include the designations of savior (sōtēr | σωτήρ) and healer or physician (iatros | ἰατρός). But I’m more interested for now in the specific events or ideas presented in the Gospel of John.

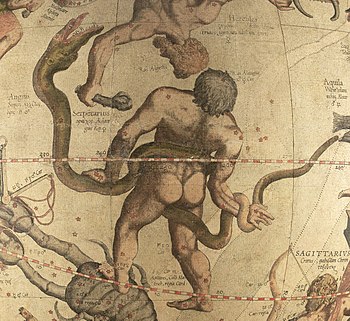

The Bronze Serpent and the Rod of Asclepius

I’ll start with the most obvious connections and proceed to the more tenuous. The most prominent correlation between Asclepius and the FG has to be the brazen serpent.

And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: so that whoever believes will in Him have eternal life. (John 3:14-15, KJV)

In the United States, especially, we tend to confuse the caduceus and the Rod of Asclepius. We should associate the caduceus with the god Hermes; hence, it’s a symbol for traders, heralds, or ambassadors. The Rod (or Staff) of Asclepius, on the other hand, is a symbol of healing.

The bronze serpent or Nehushtan in the Hebrew Bible also had specific healing properties.

And Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on the standard; and it came about, that if a serpent bit any man, when he looked to the bronze serpent, he lived. (Numbers 21:9, NASB)

Oddly enough, we read that during Hezekiah’s reign, the bronze serpent was destroyed as a part of his reform movement.

He removed the high places and broke the pillars and cut down the Asherah. And he broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the people of Israel had made offerings to it (it was called Nehushtan). (2 Kings 18:4, ESV)

An Asklepieion at the Pool of Bethesda?

In The Good and Evil Serpent, James Charlesworth tells us that the Pool of Bethesda, the site where Jesus healed the invalid (John 5) was part of an Asklepieion, i.e., a temple of healing for the god Asclepius:

It is becoming clear that there was a temple to Asclepius in Bethesda (Bethzatha) that is just inside Jerusalem and north of the Sheep’s Gate (Stephen’s Gate, Lion’s Gate). There probably also was an Asklepieion with healing baths and a room for incubation.286 [Charlesworth, James H. (2010-02-17). The Good and Evil Serpent (The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library) (p. 108). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.]

He lists a number of ancient objects found near the site (see pp. 108-109) that are most likely related to the cult of Asclepius, culminating in a “magnificent example of ophidian [of or relating to serpents] iconography” found north of the Temple Mount. Known as the “Vase of Bethzatha,” this object appears to be connected to the nearby Asklepieion.

It is conceivable that the object was associated with the Asclepian cult that was located just east of where it was discovered—that is, inside Stephen’s Gate to the north and where the author of the Gospel of John places the five-porticoed Bethzatha or Bethesda (Jn 5:1–2). There is abundant evidence that Bethzatha was a popular site for healing in the Roman Period. An Asclepian cult, not necessarily an Asklepieion with sleeping quarters, may have been located at the pools of Bethzatha. [Charlesworth, James H. (2010-02-17). The Good and Evil Serpent (The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library) (p. 113). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.]

The Resurrection of Lazarus

John the evangelist moved the Temple disturbance to the beginning of his Gospel, insisting that the resurrection of Lazarus caused the Pharisees to seek Jesus’ death. In fact, John claims that the crowds that welcomed Jesus into Jerusalem with shouts of “Hosanna!” had come not only to praise Jesus, but also to see Lazarus, “whom he had raised from the dead” (John 12:9).

Because Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead, the people were even more attracted to him, which stirred up feelings of worry, resentment, envy, and fear.

So the Pharisees said to one another, “See, this is getting us nowhere. Look how the whole world has gone after him!” (John 12:19, NIV)

The resurrection of Lazarus was the last straw — the precipitating event that brought about Jesus’ demise. Similarly, Asclepius was struck dead after resurrecting someone. The myth varies in the telling, but the common threads have to do with the raising of a dead man, the killing of the savior, followed by the savior’s resurrection. In one version, Zeus strikes down Asclepius with a lightning bolt, but then raises him to the heavens as the constellation Ophiucus.

Fluids from Chest Wounds

After Perseus killed the Gorgon, he offered the head to the goddess Athena. According to the myth, she put the head on her shield to ward off enemies.

She gave some of Medusa’s blood to ASCLEPIUS, the god of healing, and while blood from veins on the Gorgon’s left side brought only harm to man, that from veins on her right side could raise the dead. According to Euripides, Athena gave two drops of the blood, again one of them a deadly poison and one a powerful medicine for healing, to Erichthonius. (Jennifer R. March, Dictionary of Classical Mythology, p. 209)

It was this blood, then, that gave Asclepius the power to resurrect the dead. We recall that only in John’s gospel does the centurion prove that Jesus has died by piercing his crucified body with a spear. John tells us that blood and water poured out, thus proving he was already dead.

The FG doesn’t tell us which side was pierced, but it was long assumed to be the right side, since the purpose was not to kill him (i.e., to penetrate the heart), but to prove that death had already occurred. Later artists would typically show the soldier thrusting his spear upward through the right side, often with blood and water visibly spraying in different directions.

It was, of course, later understood that the two fluids, blood and water, represented the two key sacraments of the faith — namely, the Eucharist and baptism.

I’m not aware of any scholar who has drawn parallels between the Gorgon’s blood and the piercing of Jesus on the cross. However, to be quite honest, there’s a great deal of material on the subject of Asclepius and Jesus, and I’ve only scratched the surface.

Conclusion

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I like the idea of not necessarily referring to the apologetic titles of the gospels, but FG for fourth is problematic because there is no way to distinguish it from first. Yet, the anchoring effect of the “names” given to the gospels probably is one of the key contributors to confusion about their contents. Perhaps naming the gospels with ordinal numbers, 1, 2, 3 and 4 would be reasonable.

I often have to pause and think when NT scholars refer to Mark as the “second gospel,” since I tend to think of it as the first (chronologically). In any case, the term FG for John’s Gospel is pretty common (if slightly pretentious), since it’s hard to swing a dead savior without hitting some guy named John. There’s the Baptist, the Elder, the nutjob on Patmos, the brother of James, and whoever it was that wrote the Fourth Gospel.

“Crop rotation in the fourteenth century was considerably more widespread after John?”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=12W34XWIQwU

“It’s only University Challenge!”

Im no linguist but this ‘gall’ usually makes me think of kohl for some reason. As in when Jesus rubbed his spit in the blind man’s eyes. I looked it up and the Biblical Hebrew for Kohl was kaḥal (“blue”).

Gall

“bile, liver secretion,” Old English galla (Anglian), gealla (West Saxon) “gall, bile,” from Proto-Germanic *gallon “bile” (cognates: Old Norse gall “gall, bile; sour drink,” Old Saxon galle, Old High German galla, German Galle), from PIE root *ghel- (2) “to shine,” with derivatives referring to bright materials and gold, and bile or gall (see glass). Informal sense of “impudence, boldness” first recorded American English 1882; but meaning “embittered spirit, rancor” is from c.1200, from the medieval theory of humors.

Glass

The PIE root also is the ancestor of widespread words for gray, blue, green, and yellow, such as Old English glær “amber,” Latin glaesum “amber” (which might be from Germanic), Old Irish glass “green, blue, gray,” Welsh glas “blue.”

Hi, Don. Did you mean to put that comment here?

“It was, of course, later understood that the two fluids, blood and water, represented the two key sacraments of the faith — namely, the Eucharist and baptism.”

I would submit that in the iconography of the crucifixion and that of tauroctony there are several overlapping. I talked about it here: https://www.academia.edu/2549382/Christianity_and_Mithraism

But I want to dwell in particular the escape of fluids: water and blood in Christianity, semen and blood in Mithraism; as somewhat different, they could never be the same, we must examine the message.

For example, in several successive representations (Durer, Perugino) the mixture of blood and water is collected in a cup that is certainly a reminder of the cup with which Jesus, according to Christians, would introduce the mystery of the Eucharist where the water (element that draws too Mithraism) becomes bread.

I think that the meaning of these elements is still deeply hidden.

Blood and water [breaking]: Birth! … for Asclepius’ sake!

Another instance of blood mixed with water is found among the sacrifices for the cleansing and reconciliation of the leper in Leviticus 14. The blood and water are sprinkled over the live bird who then flies off, sprinkling the land with the mix, and again the mix is used to cleanse the dwelling of the leper.

There are many links between Jesus and physicians. Like Thomas, probing his wounds. “Luke the physician” as he was once called. And many have speculated that Jesus’ legend came from the “Therapautae”; the therapeutic or healing ascetic community outside Alexandria Egypt. This would complement links to Greek medicine too.

Interestingly though, while Jesus was often pictured linking to snakes – like Moses, lifting up the snake in the wilderness, Jesus is lifted up; Jesus tells his followers to be “wise as serpents” – of course at the same time, snakes were often associated with poison, evil, and the devil himself. Suggesting a veiled criticism of Jesus and his followers, even in the Bible itself. (A lingering Jewish rejection of him?).

By the way; is the gall bladder blue? And bile is yellowish to bluish?

There is a useful brief, annotated sifting of the Luke-Acts “physician” aspects by a Christian writer, Reuben Hubbard, “Medical Terminology in Luke”, Ministry Magazine on-line. The blood-and-water from the crucified body may have been evidence of cardiac tamponade. (But only if Jesus existed and was lanced in fact.)

The Jewish allegation was that Jesus learned “magical arts” in Egypt, which housed Therapeutae in Alexandria who were similar to Essenes (holy healers). Some miracle cures attributed to Jesus may have employed medical knowledge, plus hypnotism and psychoactive substances (see e.g. Morton Smith, Clark Heinrich & Daniel Merkur).

I fully agree with the second statement, but not with the former. The blood and water, crucifixion not being real, is only an allegory.

So are snaky or convoluted hings like Jesus and medicine, good or bad? Over on Le Donne’s The Jesus Blog, we considered whether God had abandoned Jesus in the end. My position is that the Bible itself is far more equivocal about Jesus than preachers tell you.

You are permitted to comment on The Jesus Blog? You are indeed privileged! They refuse to allow me to say a word there. They even excised comments of mine that they had let through earlier.

I have downloaded your interesting essay on Christianity and Mithraism, and may touch on its astral aspects if I decide to add a comment on an earlier article about “Acharya S”. Jesus was probably a real person; Mithra probably was not.

The NT narratives have been influenced by OT prophecy and by symbolism.

I think this intervention is addressed to me because I think I’m the only one to have made an association Christianity-Mithraism, so I answer.

“Jesus was probably a real person; Mithra probably was not”

I do not think I’ve ever said that Jesus was a real character. Maybe you should also read my other article https://www.academia.edu/4494891/The_Gospels_were_and_are_allegorical_stories

That was my opinion, not yours.

In fact, I spoke to emphasize that it is wrong.

I have read both your recommended articles, though not yet the Kindle edition of your argument that “the whole Gospel narrative” was “based on an allegorical scaffold” primarily related to solar mythology. I was led to understand that you did not preclude the historical existence of an individual Jesus and now see that you deny ever saying that he was a real character.

Do you know the work of Joscelyn Godwin regarding equinoctial precession and cultural sequence?

Unfortunately, I know very little about literature in English language that I find hard to translate. I help myself on the internet with Google traslator.

My reference in the synopsis of my book, to a possible historical figure behind Jesus, does not refer to the character of Jesus expressed in the Gospels, but to The Egyptian of Acts and Joseph, which may have given rise to a first hermetic and initiatic sect that I try to outline in the chapter devoted to the Jesus of History. Of this I have not spoken in any of my articles because I consider the topic only a complement and a hypothesis to be explored.

Jesus of Gospels, being a solar allegory, never existed.

Importantly, Josephus tells us that around 4 BC or so, Jews or others rioted against the weakened rule in Jerusalem. In response we are told, the local Roman ally Varus crucified 2,000 of them.

In this crowd of 2,000, statistics suggest that about 7% of them, or 140, would have been named Joshua. Or in Greek, “Jesus.”

But if so, this suggests that the whole idea of a crucified Jewish hero named “Jesus” could have come from not one, but hundreds of examples or sources. None of whom alone and in himself however, would likely be an historical Jesus. Jesus would likely be a composite in part, of the 140 persons of that name crucified in 4 BC.

Who made this composition and what would be its purpose?

A PS on crucifixion in Josephus without discussing “his” two references to Jesus the so-called Christ.

There seems little doubt that the text we have of Luke-Acts depends on Josephus or on his own sources. But his story of the survived victim of crucifixion and the similarity of his given name to the “best disciple” who supposedly buried Jesus in his special garden tomb are issues I have not yet found adequately discussed by NT apologists.

See (1) “The Flavian Testament. Josephus & Gospels, page 3” @ http://carrington-arts.com/cliff/JOEGOS4.htm

& (2) “Rejection of Pascal’s Wager: The Burial” @ http:www.rejectionofpascalswager.net/burial.html#joseph