As a follow up to my previous post here is more detail of Michael Goulder’s argument that the Lord’s Prayer was originally composed by the author of the Gospel of Matthew. I am referring to Goulder’s “The Composition of the Lord’s Prayer” as published 1963 in The Journal of Theological Studies.

Goulder begins by setting out the five propositions generally accepted as the explanation for how the Lord’s Prayer came to be recorded in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. He finds each of these propositions unsatisfactory. From pages 32-34 (excerpts with my formatting and bolding):

- The Prayer was composed by Jesus, incorporating phrases from the synagogue liturgy, but in a unique combination and meaning.

-

If the Prayer was composed by Jesus and taught to his disciples, then it is the only thing of the kind he ever did. . . . [T]here is no very obvious reason why he should so have done [i.e. passed on this one teaching to learn by heart — which is the same principle as setting down one’s teaching in writing].

-

-

The Prayer was universally used in the primitive Church, but a number of slightly different versions of it became current, either in the Palestinian churches, in Aramaic, or later when it was translated into Greek.

-

Where are the variant versions to have originated? It is hard to believe that a dominically composed Prayer should have been corrupted anywhere without authority immediately objecting.

-

-

St. Mark does not include the Prayer in his gospel for reasons best known to himself; but in general St. Mark felt at liberty to include only a proportion of the teaching of Jesus known to him, seeing the gospel as primarily the acts of Jesus.

-

The theory that St. Mark might have felt at liberty to leave out the Prayer, along with other of Jesus’ teachings, is at variance with (1), which maintains that Jesus thought it to be the most important piece of teaching he ever gave. If Jesus thought this, it is hardly likely that St. Mark thought otherwise; and it is especially difficult to maintain that he did when he records teaching very close to the Lord’s Prayer at xi. 25 f.

-

-

Of the two versions preserved in our gospels St. Luke’s is likely to be nearer the original, as it is shorter, and liturgical forms tend to grow more elaborate in time.

-

[Matthew’s and Luke’s versions of the LP each show strong traces of their respective styles; Luke’s LP wording lapses into the same awkwardness in which he falls when adapting Mark’s gospel.] This means . . . that the Lucan version is not likely to be a Greek translation of the original Lord’s Prayer; and we have a highly elaborate hypothesis on our hands in consequence. [That elaborate hypothesis involves attempting to work out the history of the prayer through three unknowns: Q, L (sources or a special version of Q known only to Luke) and an Aramaic original as the root of both.]

-

-

St. Matthew’s version shows strong traces of Matthaean vocabulary and style, and is an embroidery upon the Prayer as received by him in the tradition.

-

The most remarkable assumption of all is that two generations after the Prayer had been committed to the Apostles St. Matthew should have been at liberty to expand and improve it at will. . . . A sound argument must run: it is impossible that St. Matthew should have had licence to amend a Prayer composed by Jesus, and it is a fortiori impossible that his scribes, or the author of the Didache, should have had this licence. Therefore Jesus did not compose the Lord’s Prayer.

-

The Invention of the Lord’s Prayer

Goulder then moves on to his own argument (italics original), p. 35:

We shall find that a simple hypothesis satisfies all the evidence. Jesus gave certain teaching on prayer by precept and example, which was recorded for the most part by St. Mark. This was written up into a formal Prayer by St. Matthew, including certain explanations and additions in Matthaean language and manner. St. Matthew’s Prayer was then abbreviated and amended by St. Luke.

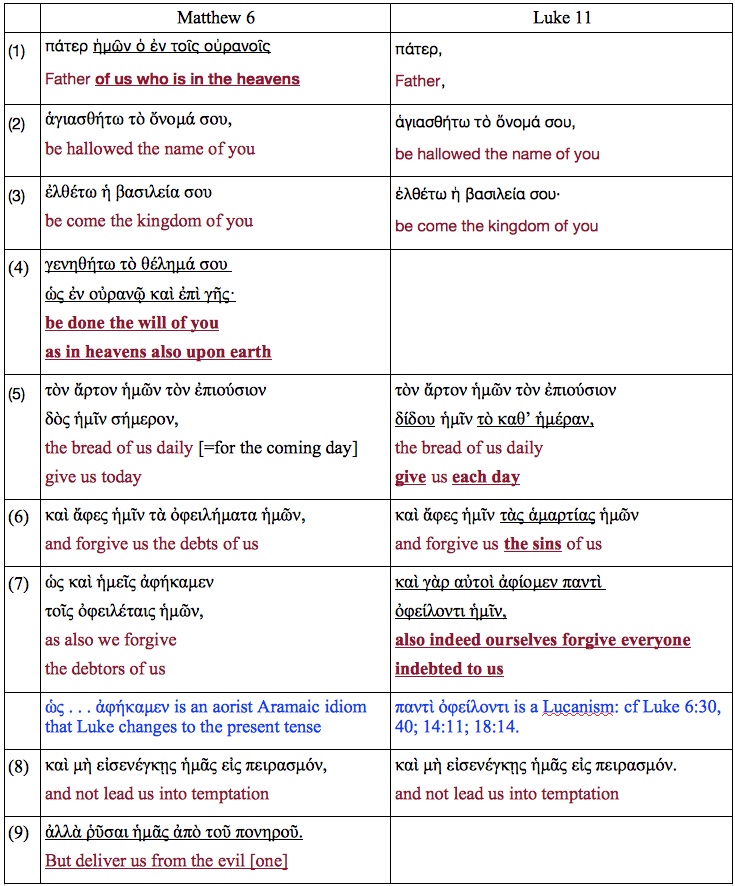

First, here is the Lord’s Prayer as we find it in the gospels of both Matthew and Luke. I copy Goulder’s numbering of the clauses. The underlined and bolded phrases highlight the differences between the two versions. The English translation is my own crude word-for-word addition to Goulder’s table for the benefit of readers not knowledgeable of Greek but interested in understanding some of the details of the arguments. I have added in blue brief points of Goulder’s that I omit from the main discussion.

It All Began With Mark

The Gospel of Mark is short on teaching material from Jesus. (Perhaps he wrote prior to the concept of Jesus being a significant teaching figure. But that’s another topic.) The only reference in this gospel to Jesus’ teaching about prayer comes after the disciples express their shock at Jesus power to kill a fig tree with a curse. It is in Mark 11:22-25 (KJ21).

22 And Jesus answering, said unto them, “Have faith in God.

23 For verily I say unto you, that whosoever shall say unto this mountain, ‘Be thou removed, and be thou cast into the sea,’ and shall not doubt in his heart, but shall believe that those things which he saith shall come to pass, he shall have whatsoever he saith.

24 Therefore I say unto you, what things so ever ye desire when ye pray, believe that ye receive them, and ye shall have them.

25 And when ye stand praying (προσευχόμενοι), forgive (ἀφίετε) if ye have aught against any, that your Father also who is in Heaven (ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς) may forgive (ἀφῇ ) you your trespasses.

Matthew has turned the Jesus’ instruction on prayer in Mark’s Gospel into a formalized prayer for use in the churches. The key point of Jesus’ instruction — forgiveness — is central to the prayer in Matthew. Goulder remarks that because Matthew has not done justice in his prayer to the related point in Mark that God himself will judge us according to the extent we ourselves forgive others, he has added an explanation immediately following:

14 For if ye forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you.

15 But if ye forgive not men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.

Matthew has thus used material from Mark to build up his three-fold teaching of Jesus in this section of the Sermon on the Mount: Alms, Prayer and Fasting.

But how does Goulder explain Matthew’s change of Mark’s “trespasses” to “debts”?

The only change that he makes in the Marcan language is to substitute ‘debts’ and ‘debtors’ for ‘trespasses’. The reason for this is obvious: he could not write ‘. . . as we have forgiven our trespassers’ because the last word would make no more sense in Greek than in English. But the notion of offences being debts is deep in the Aramaic thought of St. Matthew, and receives a full exposition later in the gospel (Matt, xviii. 21 if.):

Lord, how often shall my brother sin (άμαρτήσει) against me and I forgive (άφήσω) him? Jesus saith unto him . . . . Therefore is the kingdom of heaven likened unto a certain king which would take account of his servants. And one owed (οφειλέτης) him ten thousand talents. . . . Then the Lord loosed him, and forgave (άφήκεν) him the debt . . . . So likewise shall my heavenly Father do also unto you, if ye from your hearts forgive (άφητε) not everyone his brother.

The moral is the same. The words ἁμαρτία [sin], όφείλημα [debt], παραπτῶμα [trespass] are interchangeable, όφείλημα [debt], οφειλέτης [debtors] are the most convenient to use in an epigrammatic prayer.

A Hint of Aramaic? Nearer to Jesus?

We know that some scholars have leapt to the conclusion that any hint of an Aramaic idiom behind the Greek words relaying the sayings of Jesus is evidence that we are close to the original words of Jesus. Mercifully Goulder does not “reason” so fatuously. Goulder reminds us that “Matthew” (for convenience I use the name as the author of the Gospel) was probably himself living in Aramaea (Syria) so that Aramaic phrasing was familiar to him.

What Has Luke Done with Matthew’s Debts?

Luke changed Matthew’s “debts” to a word that he found “more general and meaningful”. The word for sin (ἁμαρτίας) comes more naturally to Luke, too, being found in Matthew’s gospel 7 times, in Mark’s 6 and in Luke’s 11.

We saw in the previous post that Luke has not been consistent here and that he reverts to “debts” in the next lines. For Goulder this is a common failing of Luke. He (Luke) finds himself repeating this sort of inconsistency when he copies and adapts the Gospel of Mark, too. In the parable of the sower he omits the first reference to the rootlessness of the seed but later in the interpretation of the parable he reintroduces it; Mark used it in both halves. In the healing of the paralytic he leaves out the words “take up they bed” spoken by Jesus in Mark’s Gospel and that are addressed to the scribes, but then repeats them as they are found in Mark when he addresses the paralytic.

Others have objected that Luke would not break up the beautiful symmetry of Matthew’s rhetoric. Goulder responds:

If it be asked how St. Luke could have borne to destroy the epigrammatic balance of the Matthaean Prayer, we must answer that St. Luke had not quite the ear for Semitic epigram possessed by his two predecessors. Compare his changes to Mark. . . . .

He follows with a comparison of the following: Mark 4:20 and Luke 8:15; Mark 8:36 and Luke 9:25.

Mark Again

Recall from above Jesus’ teaching on prayer that we find in Mark’s Gospel.

And when ye stand praying, forgive if ye have aught against any, that your Father also who is in Heaven (ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς) may forgive you your trespasses.

And so Matthew has Jesus address our “Father who is in heaven” as the opening words of the prayer.

Jesus in Gethsemane Influences the Lord’s Prayer

Father

Matthew naturally turned to the one famous moment in Mark’s Gospel where Jesus was praying himself and where he began by addressing his Father.

Mark 14:36 (KJ21)

And He said, “Abba, Father, all things are possible unto Thee. Take away this cup from Me; nevertheless not what I will, but what Thou wilt.”

From Paul’s letters (Galatians 4:6 and Romans 8:15) we know that addressing God in prayer in the Aramaic Abba, meaning Father, was well known to the churches. Mark is deploying a church practice, it seems.

When Matthew copies Mark 14:36 in his own narration of Jesus’ Gethsemane prayer he drops the Abba and writes only “My Father” as Jesus’ opening words. Luke is even briefer and drops the pronoun: Jesus begins (as he does in Luke’s own version of the Lord’s Prayer) with the single word “Father”.

Luke continues the use of the solitary “Father” in Luke 23:34, 46 just as he had used it this way in the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:12, 18, 21).

Thy will be done

Mark 14:36 (KJ21)

And He said, “Abba, Father, all things are possible unto Thee. Take away this cup from Me; nevertheless not what I will, but what Thou wilt.”

Matthew appears to have taken the thought from Gethsemane and adapted it to a tighter epigrammatic fit for the more formal prayer.

In earth as it is in heaven

These words do not come from the Gethsemane prayer but the cosmic couplet does appear thirteen times throughout Matthew’s gospel compared with twice and five times in Mark and Luke. Matthew likes the sound of it.

Luke has omitted what he sees as the inessentials padding. He has already hallowed the Father’s name and called on the kingdom to come, so asking for God’s will to be done is just repetition.

Lead us not into temptation

Again from Jesus’ instruction in Gethsemane to his disciples:

Mark 14:38 (KJ21)

Watch ye and pray, lest ye enter into temptation. The spirit truly is ready, but the flesh is weak.

The word for “temptation” (πειρασμός) can mean either a severe trial or the lure of the devil. Goulder believes the former meaning, the tribulation, is the more likely meaning given that

- Jesus is praying for his own deliverance from such a severe trial (the crucifixion);

- Jesus has previously warned the disciples that they would face severe tribulations in the same way Jesus had suffered them.

So in the Lord’s Prayer Matthew has Jesus continue to warn his followers to pray that they not suffer more than they can endure and that they be delivered from the devil who is trying to destroy them this way.

Influence of a Prayer Widespread in the Primitive Churches

The call for God’s kingdom to come is most likely inspired by a common Aramaic prayer widespread through the early churches, Marana tha = “Come our Lord”.

Note Paul’s and John’s use of this prayer:

I Cor. 16:22 If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be anathema. Maranatha!

Rev. 22:20 He that testifieth these things saith, “Surely I come quickly.” Amen. Even so, come, Lord Jesus.

And also the Didache 10:6

Let grace come, and let this world pass away! Hosanna to the Son of David! If anyone is holy, let him come; if anyone is not holy, let him repent. Maranatha! Amen.

This may be close but it is not quite “Thy kingdom come”. Goulder argues as follows:

It was natural therefore for him to feel that it should be incorporated in his Prayer. Since the Prayer is addressed to Our Father’, he rephrases it, not writing, ‘Let our Lord come’, which might seem rather indirect, but ‘Let thy kingdom come’. That the two expressions were regarded by him as identical is shown by the change that he makes in the opposite sense to Mark ix. 1:

There be some here of them that stand by, which shall in no wise taste of death, till they see the Kingdom of God come with power.

Compare Matthew 16:28 There be some of them which stand here, which shall in no wise taste of death, till they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.

Meeting the Needs of Matthew’s Context

This point appears to be developed more in Goulder’s arguments published subsequent to his 1963 article. Goulder in the original article did refer to God supplying manna daily (“for the day ahead”) as an “obvious precedent” for the prayer for daily bread. We may further note, I think, the broader context of Matthew’s Jesus being modelled so closely upon Moses and the Sermon on the Mount in particular as an extrapolation from the law given to Israel in the wilderness. Certainly the Sermon on the Mount in other places continued to stress the theme of trusting God for our daily needs:

Ask, and it will be given you; seek, and you will find . . . . Or what man of you, if his son asks him for a loaf, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a serpent? If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good gifts to those who ask him? (Matthew 7:7-11)

The request for bread begins the second half of the Lord’s prayer: the first half consisted of expressions of devotion to God; the second of the petitioner’s needs.

The word Matthew used for “for the coming day” (ἐπιούσιος) was apparently rare — “even the Fathers were in doubt as to its meaning” — so Luke adds a few words (τὸ καθ’ ἡμέραν) to explain what he considered the appropriate meaning:

He therefore [adds] the explanatory phrase το καθ’ ή μέραν [= each day], words which occur at Exod. xvi. 5 and are direct evidence that the evangelists had the story of the daily manna in mind. The day-to-day note of the petition is retained, but the idea of the immediate future only is lost, and he must suppress St. Matthew’s σήμερον [=today]. Now, where St. Matthew had a once-for-all petition requiring an aorist imperative, St. Luke has a general petition requiring a present imperative. He therefore changes δός [=give as if once] to διδου [=continue giving].

Filling in the Missing Commandment

Matthew’s Gospel repeats and expands upon the Ten Commandments. Most of us know that the Sermon on the Mount is by some scholars thought to be based upon the idea of Moses/God delivering the Ten Commandments and perhaps the larger Law at Sinai.

Matthew covers all the ten commandments in some form in this gospel:

- No other gods

- Serve no idols

- Jesus in the wilderness — Matt. 4 — counters the devil with reminders to worship and serve God alone.

- Honour God’s name

- Keep the sabbath holy/hallowed

- Jesus is Lord of the Sabbath that was made for man (Matt. 12)

- Honour parents

- Compare Matthew 15:4ff

- Don’t kill

- Jesus commands not to even hate (Matt. 5)

- Don’t commit adultery

- Jesus commands not to even lust (Matt. 5)

- Don’t steal

- Jesus teaches forsaking material treasures and laying up heavenly wealth (Matt. 6)

- Don’t bear false witness

- Always speak truth; do not even swear oaths (Matt. 5)

- Don’t covet

- As #8; Luke is more direct and has Jesus warn against covetousness.

No prizes for guessing where does Matthew address the third commandment. He has spiritually heightened it (as he does the other commands) borrowing the word “hallowed” from the next verse about the sabbath.

So the Lord’s Prayer begins with references to the Ten Commandments just as so much else does throughout the Sermon on the Mount. And just as the Decalogue’s opening commandments refer to God and the latter ones to mankind, so the Lord’s Prayer is divided into the first half focusing on God and the second half on humanity’s requirements.

Goulder’s conclusion (p. 45):

The background of the Lord’s Prayer is the synagogue liturgy, as has always been asserted by commentators. For the greater part this will be due to Jesus’ attendance at the synagogue; for the lesser part to St. Matthew’s.

Even Goulder is still bound in conservative assumptions. Of course the evidence only allows us to say that Matthew knew the (necessarily literary) Jesus of Mark’s Gospel. There is no need at this point to multiply hypotheses beyond that.

Matthew was composer of the prayer:

But we have seen that, in every other respect, of the five propositions in which we originally set out the accepted view of the development of the Prayer, the exact opposite is in every case true. The substance of the Prayer was drawn from Jesus’ teaching on prayer, but the form was not Jesus’ but (primarily) St. Matthew’s. The Prayer was in consequence not in use at all in the primitive Church, and the teachings it embodies have come down to us in virtually a single version.

Mark was the beginning of Matthew’s inspiration:

St. Mark did not include the Prayer in his gospel because it had not yet been composed; but he did include the greater part of the teaching on which it was based.

Luke adapted Matthew’s version in the ways he adapted Mark:

Of the two versions in our gospels St. Luke’s is the later, and the motives for which he has altered and abbreviated his predecessor are those which lead him to alter and abbreviate elsewhere.

Matthew’s fingerprints, Matthew’s contribution:

And finally St. Matthew’s version shows strong traces of Matthaean style because the Prayer is St. Matthew’s own composition. Formal and epigrammatic syntheses of dominical teaching are the genius of the first evangelist, as mythography is the genius of the third. The Church is in St. Matthew’s eternal debt for the Prayer she not improperly calls the Lord’s.

Now that that’s done, why not look at other passages in Matthew and the other Gospels, too, to see what else we might find?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

But… but… but… but Q!!!

Great series, Neil. Thanks!

The Synoptics use “sin” 24 times in total? Very surprising to me and I suppose others who don’t know their NT very well. I think that Paul uses sin a lot, but if someone could tell me the number for some of the letters and GJohn, I would appreciate it.

The figures are for the word ἁμαρτία in the Synoptics. The word occurs 16 times in the Gospel of John if my eyesight is not failing me trying to discern the small print of my Wigram-Green Concordance/Lexicon.

17 times in 1 John. Zillions of times in the Pauline letters and Hebrews.

So the word “daily” in the Lord’s Prayer is a wild-guess translation of a Greek word found nowhere else but in the Gospels, and no one actually knows what it means???

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Gk6a-MhXMAAJdPB?format=jpg&name=small

https://x.com/_SatanWatch/status/1895623017038049403

Are you suggesting that the evangelists just made it up and that none of their readers or audiences knew the meaning of what they read or heard?

Why not scout around and check things out before spreading “gotchas”?

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E1%BC%90%CF%80%CE%B9%CE%BF%CF%8D%CF%83%CE%B9%CE%BF%CF%82

and

https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=e%29piou%2Fsios&la=greek&can=e%29piou%2Fsios0

Because I’m American and “gotchas” are a big part of the national culture and/or social discourse here.

Someone I follow on what was Twitter had commented on the original Feb 28th post which has 686,600 views and 243 comments. So I came here searching for that word and not finding anything just asked