This continues from my previous post on A.J. Woodman’s argument.

There are good reasons for approaching the Book of Acts and other historical writings of the Bible from the perspective of the wider literary culture of their day. Thucydides, the Greek historian of the Peloponnesian War, is generally thought of as an outstanding exception among ancient historians because of his supposedly well-researched and eyewitness accounts of the facts. Classicist Professor A.J.Woodman reminds us, however, that we may be advised to reconsider why we should ever think of anyone as being an exception to the ethos and culture of one’s own day.

Through these posts I am exploring the nature of ancient historiography, and by implication re-examining the assumptions we bring to our reading of the Bible’s historical books. Beginning with Herodotus and Thucydides is relevant because we will see that Jewish historians, in particular Josephus, were influenced by them. We will see that by understanding Greek and Roman historians we will also understand more clearly and in a new light the nature of the works of Josephus. And by understanding the nature of ancient historical texts we will read Acts and other historical books in the Bible with fresh insights and improved critical awareness.

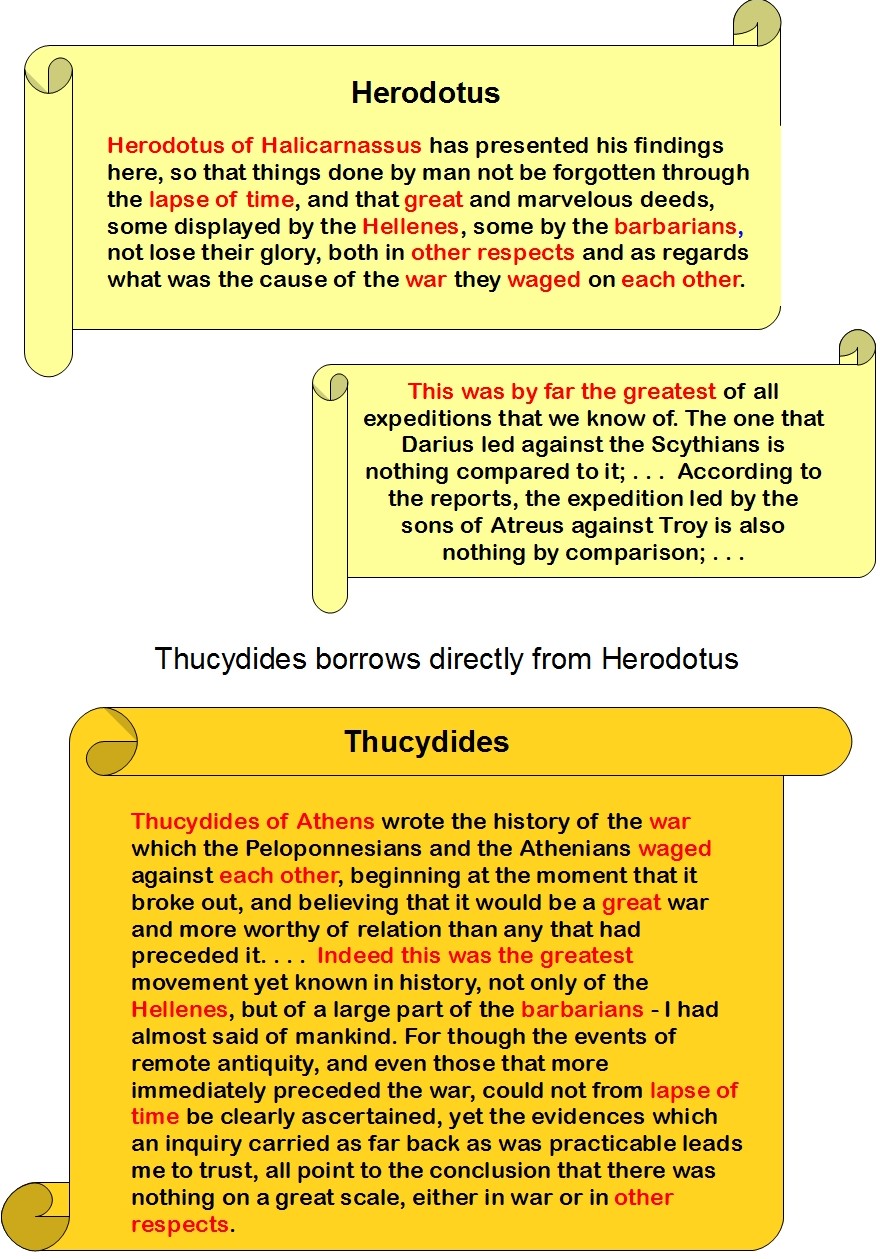

The first thing to note about Thucydides is that, for all his differences from Herodotus, he wanted his own work to be read with reference to Herodotus’ Histories. He borrowed directly from Herodotus to demonstrate to readers the superiority of his own work.

Herodotus advertized the greatness of his topic. Thucydides did the same and more so. Herodotus announced that the Persian Wars were a large-scale event? Thucydides responds by greatly exaggerating the extent of the Peloponnesian War to a far greater scale.

Far from being disengaged or objective, Thucydides has deployed standard rhetorical exaggeration in order to demonstrate the superiority of his own work and subject over those of Herodotus. (p. 7)

The translation reflects the original Greek words borrowed:

We will see that this — the choice of a most important or great topic — is a recurring theme in all historical writings. Ditto for intertextuality.

Homer the historian

Not only Herodotus but even Thucydides looked on Homer as an earlier historian. From chapter 9 of the first book Thucydides enters a detailed discussion of the Trojan War and past events generally using Homer as his principle historical source.

Thucydides went to some lengths to argue that the undoubtedly great topic Homer chose to write about, the Trojan War, was not nearly as great as the war that he, Thucydides, was about to narrate for posterity. Thucydides argued in detail how the size of the armies and navies appearing in Homer’s epic were not nearly as great as his poetic embellishments made them appear.

Thucydides concluded that even despite the poetic licence used by Homer, his own theme of the Peloponnesian War would be found to be far greater in scope and impact. Thucydides thus implied that there was no need for him to use poetic devices to magnify the greatness of his subject.

Such is the correct interpretation of chapters 9 to 21.1 of the preface of Thucydides, argues Woodman.

This is important. It means that Thucydides did not reject poetic narration as unworthy of the genre of “history”. He was not opposed to poetic epics per se to document history. He was only saying that the greatness of his topic stood on its own merits without any need for such devices.

This is why Thucydides could still look back to Homer as a predecessor of his as a historian.

Thucydides did not reject poetry as his means of writing because he considered it somehow “unscientific” or “inappropriate”. He chose to write in prose because his topic was of such importance that poetic embellishments were unnecessary.

We thus see, again, Thucydides not being so “exceptional” for his times. His view of what “history” was not really different from how Herodotus, nor even Homer, understood it.

This is worth keeping in mind. When we later see others like Josephus (and Luke) appearing to imitate Thucydides, were they also of the opinion that what they were writing was much the same as anything Homer wrote in poetic form?

Thucydides explains his method

[21.2] And, though men will always judge any war in which they are actually fighting to be the greatest at the time, but, after it is over, revert to their admiration of some other which has preceded, still the Peloponnesian, if estimated simply on the basis of its events, will certainly prove to have been the greatest ever known.

Thucydides wrote the final line in the above passage in hexameter rhythm, a line of virtual epic verse. I have replaced some phrases in the Benjamin Jowett translation with Woodman’s. Woodman introduces our word “simply” to emphasize Thucydides’ point that the events he is about to relate are self-evident in a way those clouded with poetics are not.

Just as he concluded the previous section with a note on his method (avoidance of poetics) to justify his argument, here he introduces another note on method.

His aim is to enable his readers to appreciate just how credible his detailed account is going to be.

[22.1] As to the speeches which were made either before or during the war, it was hard for me, and for others who reported them to me, to recollect the exact words. I have therefore put into the mouth of each speaker the sentiments proper to the occasion, expressed as I thought he would be likely to express them, while at the same time I endeavoured, as nearly as I could, to give the general gist [ξυμπάσης γνώμης] of what was actually said.

[22.2] Of the events of the war I have not ventured to speak from any chance information, nor according to any notion of my own; I have described nothing but what I either saw myself, or learned from others of whom I made the most careful and particular enquiry.

[22.3] The task was a laborious one, because eye-witnesses of the same occurrences gave different accounts of them, as they remembered or were interested in the actions of one side or the other.

[22.4] And very likely the strictly historical character of my narrative may be disappointing to the ear. [And for audience purposes the non-legendary aspect of my work will perhaps seem less entertaining — Woodman’s translation]. But if he who desires to have before his eyes a true picture [το σαφες] of the events which have happened, and of the like events which may be expected [are destined] to happen hereafter given human nature, shall pronounce what I have written to be useful, then I shall be satisfied. My history is an everlasting possession, not a prize composition which is heard and forgotten.

Speeches

Some have interpreted the words here translated as “general gist” as meaning that Thucydides was claiming to produce a more or less accurate outline of what was said. Woodman, not without support, argues that Thucydides makes no such claim at all. All he is saying is that he is conveying the main idea of a speech, an idea or gist that could be expressed in a single sentence. The speech itself is invented by Thucydides. The only constraint is that it presents the “main thesis” of the speaker.

This is compatible with research into how much people do, or rather ‘don’t’, remember of speeches and conversations. And Thucydides agrees. He tells readers how hard it was for him to remember what was said. We should understand that the speeches he “records” are for most part his own creation.

So why did he bother to invent so many lengthy speeches in his history?

It must be remembered that speeches feature so prominently in Thucydides’ work not simply because oratory was important in contemporary public life but also because, as is generally recognized, speeches play a significant role in the epic of Homer. (p. 13)

(Woodman does not mention it, but other works on ancient literature inform us that it was a fundamental part of education for students to practice composing speeches they could imagine various characters in the Homeric epics given in a range of hypothetical circumstances.)

The same principles would lead us to suspect that the speech of Stephen in Acts is for most part a fabrication by Luke.

Events

Thucydides impresses his audience by claiming to relay nothing that he has not himself experienced or that has been confirmed by eyewitness testimony of others. Homer also understood the importance of direct experience as a means to add credibility to his account:

Then to Demodocus said Odysseus of many wiles:

“Demodocus, verily above all mortal men do I praise thee, whether it was the Muse, the daughter of Zeus, that taught thee, or Apollo; for well and truly dost thou sing of the fate of the Achaeans, all that they wrought and suffered, and all the toils they endured, as though haply thou hadst thyself been present, or hadst heard the tale from another. (Odyssey, 8:486-491)

But is Thucydides telling us the whole story here?

First, there are occasions in his work where it is virtually certain that he is not relying on personal experience despite giving the impression of having done so. For example, it was argued many years ago by L.Pearson that Thucydides’ geographical digressions (such as 1.46.4ff. and 2.96–7) do not result from autopsy but derive from existing geographical writings. He pointed out that such digressions can be traced back through Hecataeus and Herodotus to Homer, that in Thucydides their character is usually mythological or legendary, and finally that they are often irrelevant to Thucydides’ main theme. From these observations Pearson concluded that Thucydides introduced such extraneous material because it was the kind of thing which he knew would provide entertainment for his readers. . . .

Some years after Pearson, Dover produced evidence on Thucydides’ Sicilian material which, in Westlake’s words, ‘established almost beyond doubt that it is based on a written source’. (p. 15)

Thucydides added material for purely entertainment reasons? Apparently so, despite what he claims in his introduction.

But that he sometimes did adopt a different method should not in itself cause any surprise: it is often forgotten that in this very same chapter (22.4) he claims to have excluded legendary or mythical material from his work but that that claim is not borne out by the subsequent narrative. (p. 16)

Thucydides certainly writes in a tone of authority, or as Woodman quotes another scholar, he “sustains an almost unvarying level of magisterial assurance”. Only once does he admit to having any difficulty in acquiring accurate information (7.44.1) and only once does he give two sides of an issue and infer he cannot decide (2.5.4-7).

He may express the idea “it is said” but this is not done to convey uncertainty as some have assumed. Rather, it can be shown that where he does use the expression it is generally “to tone down hyperbole”. Or where he does indicate some uncertainty it is over a trivial matter.

What does the external evidence indicate? Do the controls support the reliability of Thucydides’ history? Woodman quotes K.J. Dover (Thucydides. Greece and Rome, 1973):

‘it is disturbing to find that in those few cases where we can actually consider what Thucydides says in the light of demonstrably independent evidence…, the usual outcome is not renewed confidence but doubt’ (p. 17)

If that is the usual outcome when we can test Thucydides’ information against independent sources, it is all the more disconcerting that for the “vast majority of Thucydides’ material there is no such independent evidence with which his narrative can be compared.”

Woodman ironically remarks:

and this happy circumstance, coupled with his authorial assurance, has discouraged most of his readers from scepticism and persuaded them that his narrative is almost entirely reliable.

How much truer is this of the reactions of most people to the historical works in the Bible! Words of assurance, no means of verification, and so many will happily trust the words as “almost entirely reliable”.

Woodman reminds readers that both common experience and a barrage of scholarly tests have shown us that “entirely faithful testimonies” are the exception, never the rule. Scholars are often as naive as lay readers. The way Thucydides writes with such unqualified assurance ought to sound serious alarm warnings about his reliability, not the reverse.

Thucydides has eliminated almost all traces of the difficulties he encountered and in so doing has created an impression of complete accuracy, in order to enhance the credibility of a narrative which is intended to demonstrate that the Peloponnesian War is the greatest of all. Yet he has thereby misled the majority of modern scholars, who have mistaken an essentially rhetorical procedure for ‘scientific’ historiography at its most successful. (p. 23)

Dare we compare the assurance with which the Gospels and Acts are written?

Audience

(Realistic, not Real)

In paragraph 22.4 above Thucydides renounces the legendary and the fabulous. It is evident that he is declaring his work to be most unlike that of Herodotus. Thucydides is announcing his determination to extend the rationalizing process that “had already started with Hecataeus and Herodotus himself.”

But notice what is set against these myths. There are two types of events that are set in opposition to fables:

- things which took place — the past (the real)

- things which are destined to take place again in more or less the same fashion — the hypothetical (the realistic)

So we have “the mythical, legendary or fabulous. . . the past and the hypothetical. . .

And these three bear a striking resemblance to the familiar rhetorical division of narrative literature into the ‘historical’ (ιστορία, historia), the ‘realistic’ (πλάσμα, argumentum) and the ‘mythical’, ‘fabulous’ or ‘legendary’ (μύθος, fabula).

According to this tripartite division, what distinguishes both the historical and the realistic from the third category is the notion of probability (το εικός) . . . (p. 24)

Because Thucydides speaks of events that “are destined to take place” and that this is so “given human nature”, Woodman believes that such “probable” events are in Thucydides’ mind. (Rhetorical handbooks from this era did indeed advocate the notion of probability even at the expense of truth: see, e.g. Phaedrus, 267a.)

What Thucydides is doing here is assuring his readers that instead of providing them with cheap entertainment derived from mythical tales (they can get that from Herodotus) he is offering them το σαφες, translated above in the phrase “before his eyes a true picture”. Thucydides is offering his future audience το σαφες of two types of events: those from the past and those that are probable, given human nature.

Plutarch (and at least one other critic, Dionysius) wrote of the way Thucydides excelled in creating vividly realistic images in a reader’s mind’s eye.

In his writing he is constantly striving for this vividness (εναργεια). . . , wanting to turn his readers into spectators, as it were, and to reproduce in their minds the feelings of shock and disorientation which were experienced by those who actually viewed the events.

Here we are entering the realm of life-like imitation. Painting and poetry at their best achieved this. Thucydides and a few other historians achieved this life-like imitation of reality through the vividness (εναργεια) of their writing.

Note what Thucydides is thus offering his readers:

His readers are thus guaranteed the superior experience of ‘sight over sound’ (see Odyssey, 8:486-491 quoted above), an imitation of the experiences on which the narrative is based, but enhanced through its having been structured and shaped by the author himself. (p. 26)

So where does this leave us?

Thucydides has said his history will be based on his own experiences and on eyewitness accounts of others. We can safely suggest the latter will consist of the majority of events, but even those events experienced personally will not be easily recalled and arranged in some meaningful narrative.

It therefore seems reasonable to assume that there were certain events about which the historian felt confident and that these formed the ‘hard core’ (so to speak) of his narrative; equally, there were major areas of his narrative for which the evidence was conflicting or doubtful. It was presumably in these latter areas that Thucydides resorted to the principle of probability. (p. 26)

Thucydides has spoken of what is probable, what is likely to have happened and is likely to happen again in some form given human nature. He is thus saying that he has narrated events that conform to typical patterns in the past and are likely to recur again. (His history is in this sense an educational benefit to readers.)

Such a procedure would help to explain the presence in his work of recurring patterns, the archetypal nature of the speeches, characters and events— in short, the almost indefinable characteristic of his work which has given it its universal appeal. (p. 27)

What about the details? Do they have a place in a generalized universal narrative? Certainly.

Detailed events were regarded as an essential component of vivid description (εναργεια) and hence as providing ‘the flavour of authenticity without which history would not be itself and could not teach its lessons’ (citing C. Macleod, Collected Essays – 1983 (p. 27))

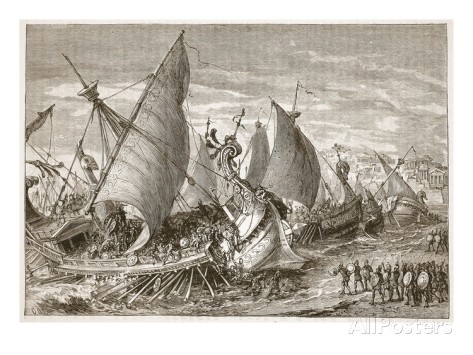

We can see how this worked when Thucydides came to describe the naval battle in the Great Harbour at Syracuse in 413 CE (7.70-1). The battle was a mass of confusion and any series of witness reports would have helped little to find a way to understand how it all developed.

Yet Thucydides’ description is extremely detailed and is generally hailed as a masterful instance of vivid writing. How did the final narrative come into being? No doubt this is one of the episodes for which Thucydides had some eyewitness information; but J.H.Finley has observed that not only the general structure of Thucydides’ account, but also several of its details, bear a striking resemblance to passages in the tragedies of Aeschylus and Euripides.

If Finley is correct, it follows that Thucydides was able to make his description even of details convincing because the tragedians had served to confirm for his contemporary audience how battles in the past had progressed and how men in battle had behaved; hence his audience will have been persuaded that these circumstances were likely to hold true both for the present and any future wars. (p. 27)

So realism, not reality, was what Thucydides strove for. He depicted a realistic battle scene, not a real one. His account was “true” but not “historically true”. It was one of those scenes which “are destined to take place again in more or less the same fashion” given the way people and the world work.

Thucydides explained that he rejected the mythical and legendary from his history. That sort of entertainment could be found in Herodotus. In place of those elements he gave his readers a most life-like and vivid account of the way things are known to happen given human nature. Where possible, he included real past events that actually had happened, too.

His own narrative has seemed true and reliable to scholars precisely because he was successful in making it both vivid and probable—in a word, realistic; but the circumstantial detail and the magisterial assurance are both equally misleading. (p. 28)

Where are the New Testament scholars and their criteria of authenticity?

So how do modern historians sift through his narrative to find the true historical core.

At this point one might expect Woodman to turn to the New Testament scholars for criteria. They, after all, assure us they have it all worked out, at least more or less. But no, Woodman disappointingly writes:

No doubt modern historians of the fifth century BC should be concerned primarily with attempting to identify the hard core of his narrative; but the task is supremely difficult because there are few, if any, criteria for drawing the line, and in the nature of the case ‘the things which took place’ are almost indistinguishable from ‘those which one day (given human nature) are destined to take place again in more or less the same fashion’. (p. 27)

Next post we’ll see that Thucydides disclaimer that he would avoid “entertaining” his readers is also contradicted by his practice. We will also soon take a look at how one of his most renowned scenes, the Plague of Athens, was a literary invention and not the famous eyewitness account it is so often claimed to be.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“At this point one might expect Woodman to turn to the New Testament scholars for criteria.”

Ah, I love dry humor.

I wonder if any historian of ancient history has ever turned to New Testament scholars for anything except, perhaps, examples of how not to write history?