[This post concludes my review of “Mark’s Missing Ending: Clues from the Gospel of John and the Gospel of Peter,” by Dr. James F. McGrath. You may want to read Part 1 and Part 2 first.]

Fish stories

At the end of part 1, I mentioned that McGrath commits the fallacy of relying on other gospels to shape his expectations of how Mark should end and then magnifies that error by looking for clues to the end of Mark’s “story” in other written gospels. I had to delay this discussion until now, because I spent so much time writing about oral tradition and “orality” in part 2.

The idea that a possible continuation of Mark’s story might be found in the incomplete, apocryphal Gospel of Peter or perhaps in the canonical Gospel of John is not a new one. McGrath reminds us that Burnett Hillman Streeter back in 1924 (The Four Gospels), building on C. H. Turner’s work proposed that very thing.

McGrath writes:

Streeter was of the view that not only the story in chapter 21, but also the appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene in the garden, were derived from the Gospel of Mark. (See Streeter, 1924, pp. 351-360)

To be fair to Streeter, he presented this notion as a “scientific guess” — a “speculation” he said should not be mistaken for the “assured results of criticism.” While he seemed rather enamored of the idea, he acknowledged that it would be difficult to prove.

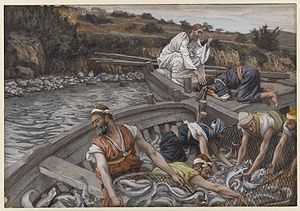

Streeter thought that the authors of the Gospels of Peter and John were aware of an earlier version of Mark that contained the appearance to Mary Magdalene and the miraculous fish fry on the lake, and that the later evangelists built on those stories.

Reliable sources

For his part, McGrath can’t believe John used Mark (i.e., a form of Mark with a longer ending) as a source for the resurrection stories in chapter 21, because the theory does not adequately explain —

- “the Johannine style of these stories in the form in which they are found in the Fourth Gospel” or

- “the awkwardness of having Jesus appear in Jerusalem to anyone after the angel announced that Jesus was going before the disciples to Galilee and that the women told no one.“

His first point demonstrates a trend among NT scholars who believe that John “must be” independent from the Synoptics, because he didn’t copy them word for word. In Streeter’s day, one could find many scholars who thought it quite plausible that the author of the Fourth Gospel was perfectly capable of reading a story in Mark (or of recalling it from a public reading) and reformulating it in accordance with his own style. As Streeter himself put it:

Whenever John adopts a story from Mark, he does so with a considerably greater freedom in regard to language and details than do Matthew and Luke. Nevertheless, except where he is conflating material from Mark with another source, John does not seem substantially to alter the main facts and the general impression. (pp. 351-352)

Of course, Streeter lived in an era of even greater credulity, a time when it was fairly common to believe that Mark was Peter’s personal secretary and that John really wrote the Gospel of John (or at least the first draft). However, a great many commonly held beliefs have fallen by the wayside, so the precious few tenuous links to the past need to be clutched in a death grip. We should try to remember this sad fact when scholars compare mythicists to holocaust-deniers. They can’t help it; it’s simply the anxiety of historicity. They need John to be independent, especially if they’re Q skeptics.

As for point two — the awkwardness of an appearance of Jesus “in Jerusalem to anyone after the angel [sic]” told them Jesus was heading north — this sequence of events is exactly what occurs in Matthew’s Gospel, and I can’t remember anyone ever calling it awkward.

7. Then go quickly and tell his disciples that he has risen from the dead, and behold, he is going before you to Galilee; there you will see him. See, I have told you.”

8. So they departed quickly from the tomb with fear and great joy, and ran to tell his disciples.

9. And behold, Jesus met them and said, “Greetings!” And they came up and took hold of his feet and worshiped him. (Matt. 28:7-9, ESV)

What McGrath must find awkward is not that Jesus’ itinerary is confused (“Hey, I thought you said he was on his way to Galilee!”), but that he would appear to the women after Mark emphatically writes that they told no one.

A New Orthodoxy

A slight digression is in order here. His second point about “awkwardness,” betokens yet another post-higher-critical phenomenon. Today’s mainstream NT scholars espouse a New Orthodoxy that, whenever possible, tends to view documents in the New Testament as representing points along the same historical trajectory. A case in point is McGrath’s understanding of Mark. Starting from the presumption of a historical Jesus, who was “almost certainly” an apocalyptic prophet-healer-teacher-exorcist, where do we plot the works of Mark, Matthew, Paul, the patristic writers, and so on? Do they exist along the same general continuum, or do they sometimes represent radically different views on Christianity and its beginnings?

New Orthodoxy tends to assume the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke are simply expansions of Mark; hence scholars of the New Orthodoxy will recognize stylistic and even doctrinal differences, but they will endeavor to harmonize the historical aspects. They will grant that the view of the Torah differed among the writers. They will agree that the Christology of Mark was not the same as that of Luke or Matthew. They will even concede that some parts, like the birth narratives, are embellishments or pure fiction. But they will continue to assert that all are witnesses to an oral and written tradition, some of which “must” go back to Jesus and his disciples.

The thesis that Mark’s Gospel is a relentless condemnation of the disciples and his family, and that Matthew and Luke deliberately subsumed and consumed Mark — i.e., that they took over Mark’s story with an eye toward replacing the earliest gospel — makes no sense to a scholar like McGrath. We should not be surprised, then, that Marxsen and Weeden don’t even register with him. (We should view his citation of Kelber, which we discussed last time, as an aberration, since he could hardly have found a scholar more diametrically opposed to his views either on the processes of oral and written composition or on the ending of Mark.)

Awkward endings?

Notice that McGrath says he would find it awkward for Mark to have told stories about the risen Jesus visiting people in Jerusalem after the resurrection, since he had relayed his promise to be seen in Galilee. However, he appears to find it not at all awkward for Galilean resurrection appearances to be in “Mark’s continuing story” despite an extremely emphatic and disastrous ending. For while many argue that 16:8 is an abrupt ending, it is also clearly a bold, decisive, and arresting ending. It’s the final, tragic failure, underscored by Mark’s use of the double negative — “. . . they said nothing to nobody, for they were afraid.” To follow this verse with the statement that they went and told Peter is more than awkward; it’s contradictory. To imagine that Mark’s post-gospel story included appearances to Peter and company in Galilee after the final catastrophe of 16:8 is to engage in unwarranted wishful thinking.

I don’t mean to single out McGrath. This selective disbelief is common in NT scholarship. Many scholars have written about how they simply can’t imagine Mark didn’t know about resurrection appearances in Galilee. He “must have” known about them — after all, how did Peter and the other disciples come to believe that Jesus had been resurrected? Rather than take Mark at his word, they would prefer to harmonize his gospel with the other three in the NT. They’ll even dig into the Gospel of Peter, if need be. Sure, they’ll turn their noses up at Crossan’s reconstruction of the Cross Gospel, but the fishing trip in the Gospel of Peter? That’s pure gold.

More Harmonizing

And McGrath hasn’t finished harmonizing the NT text. What does 1 Corinthians 15 have to say about resurrection appearances? We know Paul “must have” gotten this information from the disciples who “must have” really existed and “must have” passed it onto him. Could it be that Paul’s confession that Jesus was seen by the Twelve provides some clues?

Could the inclusion of Judas (either implicitly or explicitly) have been one of the reasons for the modification of the ending?

Modification of what ending, you ask? Well, it’s a bit hard to pin down McGrath on this point. Most of the time he seems to be talking about a theoretical ending Mark and his community knew from the oral tradition; however, at some points he argues that we can’t close the door on a written ending that was lost or suppressed. If there was a written ending, he muses, it may have fallen out of favor.

It seems fair to state that the ending of the story Mark knew (and may or may not have told in writing) fell out of favor – just as the ending we now have fell out of favor. But if the proposal we have made here about the way Mark’s story originally continued is correct, then perhaps there is more that can be said about the reasons why Mark’s ending fell out of favor, which may have resulted in, if not the intentional mutilation of the Gospel, at the very least a lack of interest in preserving the continuation of the story.

Was there a written ending? Maybe. Was it suppressed? Possibly. Did lack of interest cause it to be lost? Could be. Was it mutilated? Who can say? Are we covering all the bases? You bet.

The importance of seeing

Finally, McGrath asks whether the ambiguity of the empty tomb story (or stories) in Mark indicates a high premium placed on post-resurrection visions and not so much on the immediate contact with the fleshly resurrected Jesus in the days following Easter. In other words:

[S]ince the women tell no one, the rise of resurrection faith among the disciples in Galilee must derive wholly from the experiences which are usually described as “seeing Jesus.”

He continues:

For only a community of believers for whom visionary experiences were an ongoing part of their lives could treat the account of the earliest appearances as something unnecessary to narrate. At the same time, their resurrection faith may well have included a claim that God had rescued Jesus’ body from its dishonorable burial in the tomb, however they understood the relationship between that body and their experiences of seeing Jesus.

This terminology — “seeing Jesus” — is a crucial point. The word the young man uses in this case is ὄψεσθε (opsesthe), literally: “you will see.” Several scholars over the years have pointed out that Mark uses this same word only one other time, during the Sanhedrin trial when Jesus says, “I am, and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.” (Mark 14:62, ESV)

In his landmark work, Das Evangelium des Markus, Ernst Lohmeyer explains that “you will see” is an indication of the parousia, not the appearances of the resurrected Christ.

Because “see Him” in the Synoptic Gospels and Acts is not the term for appearances of the risen Lord; it is ὤφθη, and Paul has it only once (1 Cor 9:1 [Have I not seen, etc.?]), while John’s Gospel with its Easter report, which is in every way his own explanation, has it three times: “I have seen the Lord,” meaning appearances of the resurrected One. But even in John (not in Paul, who uses other expressions), “You shall see Him” is the fixed term for the parousia of the Lord, and it comes from the apocalyptic prophecy of the Son of Man, which Jesus used — “You will see the Son of Man (cf: 14:62, 13:26, and 9:1). So this word heralds the appearance of the resurrected One, not with reference to resurrection witnesses, but it speaks of the parousia, which is the ultimate fulfillment of the eschaton. (p. 356) [my translation of the original German, emphasis mine]

As Theodore Weeden explained in Mark: Traditions in Conflict, the young man at the tomb is telling the women that Jesus has been raised to the Father. He isn’t out and about in Jerusalem dragging around his battered human body, but has been transformed (or as Neill Hamilton put it, “translated“) into the resurrected Christ — raised, exalted, and now sitting at the right hand of God.

“He is not here. See the place where they laid him.” These words don’t refer simply to the resurrection, but to the fact that Jesus has left the world. Weeden writes:

Jesus is absent! He is absent not just from the grave. He has completely left the human scene and will not return until the parousia! He has been translated (ἠγἐρθη) [citing Hamilton in Jesus for a No-God World] to his Father. There he must await the time when the kingdom dawns in power (9:1) and he is reunited with with his community (13:26-37). (p. 110)

So, contrary to McGrath, Mark’s narrative did not imply “a certain ambiguity about the relationship between the body that had been in the tomb and the beginnings of resurrection faith,” for it is the very absence of the body that signifies the ending of Mark’s story. It’s the end of the story, because it is the end of Jesus’ presence on Earth. In fact, Mark has shifted the proof of resurrection from post-resurrection stories (cf. Paul “seeing” Jesus) to the young man’s announcement, witnessed by three women on the same day Jesus was raised.

Before Mark there is no evidence that the early church ever sought to verify its resurrection faith through recourse to Jesus’ empty tomb. Nor is there any hard evidence that the early church ever knew of Jesus’ grave being empty. (Weeden, p. 102)

Again, contrary to McGrath, Mark’s community did not rely on “seeing Jesus,” because they would not see him until the parousia. Now I fully recognize that many scholars simply do not accept this interpretation of Mark’s Gospel, but at the very least it has the virtue of using all of Mark and only Mark to explain Mark. We don’t have to invent post-resurrection stories from an oral tradition. We don’t have to appeal to other gospels — apocryphal or canonical. Finally, we can stop looking for a “lost ending,” either written or oral in Mark’s Gospel or in his community’s tradition.

One sometimes wonders if the proponents of a “lost conclusion” are not more interested in harmonizing the literary and theological characteristics of early Christian literature than with defending the integrity and particularity of the Markan composition. (Weeden, p. 46)

We know the ultimate end of Mark’s story. True, it is not the end of Mark’s Gospel, but it is foretold in his gospel. The conclusion of the story will be the parousia. When the Son of Man descends on a cloud on the day of judgment, Mark’s story will end. In the meantime, Mark’s community must wait before they will see him again.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Tim, why not submit this series, with a few modifications, as a singe article for publication on bibleinterp.com? It has a far broader relevance than as a response to McGrath’s article.

This sums up the fallacy.

It would be interesting to investigate the following, too:

JW:

Your article here is excellent but regarding:

“For while many argue that 16:8 is an abrupt ending, it is also clearly a bold, decisive, and arresting ending. It’s the final, tragic failure, underscored by Mark’s use of the double negative — “. . . they said nothing to nobody, for they were afraid.” To follow this verse with the statement that they went and told Peter is more than awkward; it’s contradictory. To imagine that Mark’s post-gospel story included appearances to Peter and company in Galilee after the final catastrophe of 16:8 is to engage in unwarranted wishful thinking.”

while I think that “Galilee” in 14:28 & 16:7 may be forged, assuming it is original, an appearance to the boys in Galilee would be consistent with the story. The related verb of 14:28 is intransitive, meaning no cause and effect relationship. Jesus will not lead into Galilee, he will just get there before they do. Having the boys go back to Galilee in failure and than having them accidently run into Jesus signing Gospels at the local Borders is consistent with “Mark”. They just wouldn’t believe he was resurrected. So Jesus’ prediction would be correct, just not in the way the Reader expected at 14:28. How, how, now what’s that word? Starts with an “I”, help me out here Neil.

“Mark’s” text is about witnessing the resurrection but the sub-text is about promoting it. His criticism of the disciples is that they were not promoting the resurrection like Paul was. Maybe they did make some kind of resurrection claims. Don’t know, we have nothing from them. But “Mark’s” point is that they were not promoting the resurrection like Paul was.

Whatever evidence “Mark” provides regarding what he thought the disciples were being credited with as witnesses to Jesus is in reaction form. So even he is an indirect witness.

Obviously McGrath is conclusion driven here as are most Christian Internet authors on the subject, pricking against the Galoads of 16:7. “Mark” has just written a Gospel with a primary theme that the Disciples never believed in miracles in general or specifically the resurrection, no matter how much evidence they had, because they lacked faith and this is contrasted with strangers who had no evidence what so ever and straightway achieved miracles because they had faith (note that the Disciples failure to believe in the resurrection despite all the evidence they had is intended to contrast with the Reader’s belief in the resurrection despite no evidence at all).

Your scholarship is above JM’s so why bring him into the discussion, it’s just a distraction.

Joseph

Although Dr. Robert M. Price has proposed that the abrupt ending of gMark is not unreasonable given the literary stylings of the day, I’m a bit uncomfortable with that (not denying the possibility but uncomfortable). On the other hand, the “missing ending” theory makes me even more uncomfortable. I have put forth a third, far more radical theory, that the “missing ending” is actually the middle part of the gMark.

In examining gMark, I have noted a number of features of aMark’s Jesus, during his ministry, that made him stand out. He walked on water which, as Jason Robert Combs pointed out in “a Ghost on the Water? Understanding an Absurdity in Mark 6:49-50” (JBL 127, n 2 (2008): 345-358), in greek literature, would indicate that he was a divine figure. He constantly traveled around the Lake of Galilee, rarely traveling by land but always by entering and exiting the Lake. He didn’t always do this in the same boat with his disciples. To the jewish mind of the time (and, probably, greek) this would have suggested someone who was traveling to and from Sheol through the Lake. His trip out of the Lake and directly up the Mount (gMark 5) to give his sermon and heal the afflicted can be seen, in a spiritual sense, as his ascending the Mountain of God as he (presumably) also did for the transfiguration (gMark 9).

If we accept these and other incidents as indications that much of gMark is about the spiritual rather than physical Jesus, then we have to ask, when did he “pass over”? My suggestion is that the death and resurrection scene of gMark was originally much earlier in the gospel and that many of the Jesus incident recorded by aMark were actually post-resurrection appearances. It is possible that this occurred by as simple a method as a rearrangement of scroll pieces when the scroll was copied. In this scenario, the women wouldn’t have had to tell anyone about the resurrection of Jesus because he soon re-appeared and, in fact, much of his recorded ministry was post-resurrection.

The reason that I bring this up here is simply to point out, after yourself, that McGrath’s theory isn’t unreasonable but that there are enough other reasonable theories that McGrath’s emphasis on a single theory shows a marked conclusion-driven motive to his proposal.

Chapter 4 of Patrick J. Madden’s Jesus’ Walking on the Sea is entitled “A Displaced Resurrection Narrative.” I happened to find a copy last year at a reasonable price, but now I can’t recall where I put it. Maybe I can find it over the weekend. In the meantime, there are viewable bits here.

https://books.google.com/books?id=d6RNLSC1hGEC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

I agree with you that there are more reasonable explanations than scripture ninjas, followed by mass amnesia.

Note also Mark 1:35-39

Mark 16:2 Very early, just after sunrise the women came to the tomb, but Jesus is not there

Mark 1:35 Very early in the morning and still dark Jesus got up and left the house

Mark 16:7 The young man tolds the woman, that Jesus is going ahead of the disciples into Galilee

Mark 1:38 Jesus tolds the disciples that he want to go to the nearby towns, all around Galilee

Mark 16:2 “καὶ λίαν πρωῒ τῇ μιᾷ τῶν σαββάτων” (kai lian prōi tē mia tōn sabbatōn): And very early on the first of the Sabbaths

Mark 1:32,35 the scene occurs after the end of the “first of the Sabbaths” in Mark’s gospel

Mark 16:6 You are looking for (ζητεῖτε – zēteite) Jesus the Nazarene

Mark 1:36-37 Simon and his friends went to look for Jesus. When they found him, they called out, “Everyone is looking for (ζητοῦσίν – zētousin) you!”

1 Cor 15:4-5 that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve

Mark 1:36-37 Simon and his friends went to look for Jesus. When they found him, they called out …

There is a book by German scholar Karl Matthias Schmidt (his habilitation). “Wege des Heils: Erzählstrukturen und Rezeptionskontexte des Markusevangeliums”

English summary: The book locates the Gospel of Mark between Vespasian’s seizure of power and a dispute about the role of the gentiles in the Christian community. In the first chapter, the author argues that a particular reading of the Gospel is necessary to comprehend the specific narrative structure. He shows that Mc 1.35-45 should be viewed as part of the Easter narrative. The apparently abrupt end and unusual structures of the Gospel thus reflects the idea that having reached the end of the text does not imply having finished reading it. Rather, the reader has to go back to the beginning. In this way, Mark broaches the issue of the gentiles’ community membership in the context of Jesus’ life. Starting from the observation that an excluded leper represents the paschal community, the second chapter asks whether the expulsion of a Christian community by the Jews triggered the dispute about the role of the gentiles. The third chapter concludes the book by relating the story of Jesus to the triumph of the gentiles over the Jews, as it is represented in contemporary narratives of Vespasian.

Tim, a late footnote to this excellent series. Given your liking for ‘classic’ scholars of genuine substance, I would direct you to Bickerman’s essay ‘The Empty Tomb’, from his 1920s Berlin period. He demonstrates that this is a story of ‘rapture’, the body being taken directly to heaven; “resurrection and rapture are mutually exclusive” (J. Weiss); thus there is no place for ‘resurrection appearances’ in Mark’s account.

To amplify Lohmeyer : “the specific character of this ‘seeing’, of the first christophanies [ ‘visions, not of the man Jesus nor of the crucified one, but of Jesus as the Son of Man in glory’- Harnack] testifies to the belief..that Jesus had been..caught up to heaven immediately after his death.”

Ok, how about this theory? John 21:1-12 is the original and almost unredacted ending of Mark. Far from testifying to an oral tradition, this would confirm mythicism further.

Hint 1: we are in Galilea, where we started from, and where we are supposed to be as told by Jesus. And there’s Peter! They aren’t even expecting Jesus, because the jewish women never told anyone, and the 12 never really believed in the Lord up to this point.

Hint 2: there’s an accidental mini-baptism of Peter (finally!) in typical Markan style, with garments and all: Mark starts with a BIG baptism and ends with a little hidden one, right after a huge symbolic baptism (the young boy in the tomb). Mark is still not empowering Peter, but belittling him.

Hint 3: Mark starts with fishermen, boats and nets, ends with the same guys doing the same stuff.

Hint 4: Initially they don’t recognize him: a new body, a pauline idea dear to Mark. Is this typical of John?

Hint 5: This time they catch not fishes, but men, as promised at the beginning of the story. It is pretty obvious that those 153 can’t be fish, but must be some reference to men of some kind. More on this later.

Hint 6: The disciples are now 7, not 12. The beloved disciple is probably invented by John, but they are still 7. To make up the number there are even twins?? Romulus and Remus?! They are no more jewish, they are gentile, or at least as hellenized jews they should go converting the gentiles, not the jews. That’s Mark 8:17-21.

Hint 7: They finally understands that he was the Lord, and this time nobody needs to ask anything!

But the biggest hint of all is the catch of 153 men, what does that mean?

Mark is an allegory for the destruction of the temple, and the tumultuous relationship between gentiles and jews. The jews never do the right thing, while the gentiles do the right thing even when told otherwise. Mark 5 talks about an unstoppable roman army besieging Jerusalem, and only Jesus can stop it by converting the enemy army/empire to the Lord, surely not the jewish rebels who are refusing Christ and will be easily crushed. The bleeding jewish woman and the (dead?) daughter of Jairus (a jewish priest) represents Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple, only Jesus can heal that wound, not more jewish tradition, or worse yet: more war. Plus Mark is a huge retelling of the story of Elijah/Elisha. Guess where that 153 comes from?

It HAD to be 2 Kings 1 :

50 soldiers plus their captain go after Elijah, and perish due to fire from above.

50 more soldiers plus their captain go after Elijah, and perish again.

Finally the next wave of 50+1 ask Elijah to collaborate. And he does!

It is a very violent story, but it ends with a single man of god submitting an entire army with no fighting. That’s exactly what Mark has in mind for Jesus, and is pretty much what Jesus does at Gerasa.

John probably understood the Kings 2:1 reference, and expanded on it with the thrice questoning of Peter (or maybe it was still part of Mark in some way), but the (anti)military connotation of this ending appears to me as very Markan.

Now, John is very baptism/Elijah oriented too, and could come up with the 153 fishes by himself, but does his gospel have the same (anti)military undertone of Mark? He’s missing the gerasene demoniac scene: maybe he is replacing it with this reference? Does John understand this meaning of Mark? Is he writing on the eve of the Bar Kockba disaster, or after it?

He is also missing the Baal-Zebub reference, and it is a very powerful one, since Ahaziah consults the wrong god, just like the jews refuse to listen to Jesus: i like the abrupt ending at Mark 16:8, but I can’t stop thinking that tacked on to the end of Mark John 21:1-12 fits like a glove… Plus the gospel of Peter gives some corroborating evidence.

But i don’t know John very well, i’m currently in my “Markstruck” phase, can’t read anything else, i’m surely missing something.

By the way, the only place i found showing a link from John 21:12 to 2 Kings 1 is this one:

http://hermeneutics.stackexchange.com/questions/890/what-is-the-significance-of-153-fish/7650#7650

Is this common knowledge? I can’t find anybody else mentioning it.

So John originally ended at chapter 20:

https://web.archive.org/web/20130604013914/http://www.michaelturton.com/Mark/GMark16.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20110408191854/http://pages.sbcglobal.net/zimriel/Mark/

even more reasons to think this is the proper ending of Mark: who else could write John 21?

Evan Powell, The Unfinished Gospel, also argues that John 21 was based on the original ending of Mark. See also Michael Turton’s Commentary — Michael points to a review by David Ross that can now be found at http://web.archive.org/web/20110408191854/http://pages.sbcglobal.net/zimriel/Mark/

As neat as the solution sounds I still hold some reservations. The language of John 21 is very “Johannine” despite overlaps with a few words found in Mark. (John’s gospel, I believe, is based on Mark’s anyway.) I think 16:8 is a more fitting conclusion (thematically and structurally when compared with the opening of the gospel and other ambiguities in gMark) than many accept. Moreover, in ancient literature it is not uncommon to find what appear to be ‘afterthought’ chapters or ‘secondary’ endings. For this reason I don’t think we should be too quick to assume that John 21 was a much later addition to the gospel. It may have been, but I keep the alternative possibility in mind, too.

If Mark did have a John 21-like ending originally we would expect to have some further evidence in the literature of it, too, I think.

So yes, I do agree it is a possibility that John 21 is a redaction of an original ending to Mark but I can’t personally go beyond that yet.

when mark has the women flee, does that mean that he thinks that the women were consumed by fear that they had to seek safety in flight?

this means that the “good news” was not good enough to balance out with fear, right?

I think it is irony* by Mark. All through the gospel, Jesus tells people to not tell this and they tell anyway. Here, they are supposed to tell. The ending is abrupt. Mark is written as a chiasm and the ending should be something like, “So they told all the guys ‘Capernaum’s where you outta be, so they loaded up the camels and they moved to Galilee,” But it ends with a pregnant pause that would have explained why the leading followers would have been caught up in the destruction of Jerusalem.

*Another irony is when Jesus is being slapped around and ordered to “Prophesy!” while his prophecy that Peter would deny him is going down. There is an article on Vridar about this.