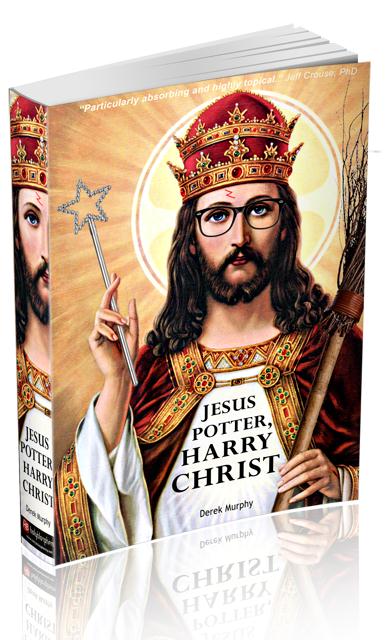

So what has kept the mythicist controversy alive despite frustrated assertions among biblical scholars that the debate was settled long ago? Derek Murphy demonstrates in chapter two of Jesus Potter Harry Christ that the modern controversy over the historicity of Jesus “has a long and substantial history, and that, in effect, the jury is still out.” Derek Murphy is well aware that some of the works he uses have been questioned and disputed with the advance of academic research. His purpose is thus limited to showing the existence and heritage of the debate.

So what has kept the mythicist controversy alive despite frustrated assertions among biblical scholars that the debate was settled long ago? Derek Murphy demonstrates in chapter two of Jesus Potter Harry Christ that the modern controversy over the historicity of Jesus “has a long and substantial history, and that, in effect, the jury is still out.” Derek Murphy is well aware that some of the works he uses have been questioned and disputed with the advance of academic research. His purpose is thus limited to showing the existence and heritage of the debate.

My goal is only to demonstrate that a modern controversy over the historical Jesus exists, that it has a long and substantial history, and that, in effect, the jury is still out.

I also want to show that certain claims regarding Jesus are not modern delusions of “fringe” scholars — in fact there are few claims made about Jesus today that were not made centuries earlier. (p. 47)

Dismay among many believers in the historicity of Jesus reminds us that few people are aware that the question can be raised at all, and that the evidence used to support Jesus’ historicity is not universally accepted.

Murphy reminds us that the question of whether Jesus ever existed as a man is as old as the earliest Christian records themselves. The authors of the epistles of John and Ignatius, with their attacks on some form of Docetic heresy that held that Jesus only appeared to be a man, and all he did was in appearance only, should unsettle any complacent acceptance that the first generation of Christians universally accepted that Jesus had lived in any sense that we would consider historical.

He then compares the questions raised by second-century writers like Justin Martyr (Christian) and Celsus (opponent of Christianity) with the central theme of his own book: b0th remarked on the common observation of their own day, that the claims made for Jesus (miracles, ethical teachings) were not unique, but were little different from the myths and teachings attached to pagan gods and heroes, and that the only essential difference was that the followers of Jesus insisted Jesus was real and not a myth or symbolic life pre-figuring Christ. There is nothing new here, of course, but it is worth revising and keeping in mind nonetheless. Derek Murphy adds his own twist to this historical record: the same arguments since the days of Justin and Celsus are used today to explain the difference between the otherwise very similar Harry Potter and Jesus Christ. Harry is fiction, Jesus is real.

The Modern Debate

Derek Murphy outlines the contributions of many names questioning either the historicity of Jesus or the possibility of knowing anything about the historical Jesus (given the extent of mythical overlay) from 1600 to the turn of the 20th century. Giordano Bruno compared the gospels to pagan mythologies, and burned at the stake for his efforts; G. E. Lessing and Voltaire were pioneers in subjecting the gospels to rational inquiry; (Murphy mentions Reimarus in passing but I would have liked a little more detail on his contribution, too); Constantin-François Volney and Charles François Dupuis initiated the hypothesis that the stories of Jesus were based on astral and solar myths; Bahrdt and Venturini linked the idea of Jesus with the Essenes and “secret wisdom from Babylonia, Egypt, India and Greece.”

Murphy acknowledges that scholarship has moved on since many of these early theories. He is demonstrating, however, that the evidence for the historical Jesus is too insubstantial to resist the questions raised and attempted alternative explanations.

He briefly covers the works of Thomas Jefferson, Reverend Robert Taylor (founder of the Christian Evidence Society, and who was jailed for his promulgation of the nonexistence of Jesus, and the “Devil’s Chaplain” influence on Charles Darwin’s life, although Murphy does not raise this latter detail), David Friedrich Strauss and Bruno Bauer (who doubted not only Jesus but Paul, too) — William Wrede in his The Messianic Secret (1901) is noted as repeating many of Bauer’s ideas — Ernest Renan and Kersey Graves (author of The World’s Sixteen Crucified Saviors).

In the wake of the discovery of the Rosetta Stone that enabled the translation of Egyptian writings there was a flurry of comparisons of Christianity with Egyptian myths, and Murphy summarizes the works here of W. R. Cooper and Gerald Massey.

Murphy moves on to the publications of John Mackinnon Robertson, G. R. S. Mead, Thomas Whittaker and Arthur Drews and others. Unfortunately Murphy quotes Maurice Goguel’s summary of M. Couchoud’s mythicist view (similar to Earl Doherty’s in that Paul’s Christ is argued to be a heavenly being) as if it were Goguel’s own view. Goguel was, of course, critiquing the mythicist arguments.

This section of the history of the mythicist tradition is rounded off with the significance of Bultmann who, while not a mythicist, declared that the historical Jesus is beyond the scope of rational inquiry:

I do indeed think that we can know nothing concerning the life and personality of Jesus, since the early Christian sources show no interest in either, are moreover fragmentary and often legendary; and other sources about Jesus do not exist.

In 1927 the famous philosopher Bertrand Russell could express doubts that Jesus ever existed in his famous lecture Why I am not a Christian.

Murphy sees this period (dominated by Bultmann) as a turning point into the inquiry into the historical Jesus. From here many branched into studies of comparative mythology and psychology, while others attempted to uncover the historical Jesus by removing all the layers of myth over his story.

Mythology, Archetypes and the Subconscious

Murphy goes into a little more depth the works of each of James George Frazer (The Golden Bough), Sigmund Freud (The Interpretation of Dreams and Moses and Monotheism), Carl Gustav Jung, Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell (The Hero with a Thousand Faces and The Masks of God.) Murphy acknowledges the flaws of some of this earlier research, and the fact that much of it is now dated. What remains of significance is that it revealed the universal aspects of the myths underlying Christianity. Christian apologist C. S. Lewis is said to have acknowledged this positive contribution, yet believed that it did not threaten Christianity because this was a genuine historical expression of that universal myth.

Criteria of Double Dissimilarity

Murphy brings readers up to date with scholarly method still used today in the search for the historical Jesus — the criteria of double dissimilarity (CDD). Ernst Käsemann and Norman Perrin expanded and consolidated the method Bultmann had initiated, and Murphy lets these two modern scholars explain the limited nature of historical resources for the historical Jesus and their particular slant on CDD in their own words. CDD seeks to establish confidence in the discovery of an original saying of Jesus by removing any word that we have reason to believe originated with pre-Christian Judaism or Christian tradition itself. But given how scant is our evidence for both first-century Judaism and Christianity, Murphy points out that it is presumptuous to assume that any untraced data did not indeed belong to either of these institutions.

Murphy rightly notes that CDD is only possible if one first removes all the mythological and pagan elements from the gospel narratives. These are a priori assumed to be much later additions to the traditions about Jesus. So this leaves scholars with a hypothesized historical figure to pick up whatever in the gospels cannot be traced to Jewish or Christian traditions. In other words, in the absence of direct evidence for the existence of Jesus, Jesus is assumed as a hypothesis and is fleshed out with whatever scholars select from non-Jewish and non-Christian tradition, and of course non-mythical and non-pagan data.

Jesus the historical figure is the binding element given to any untraceable idea, phrase, philosophy or theology from a specific time period. (p. 59)

This is the method at the heart of the more well-known and very diverse accounts of what Jesus “might have been like” by scholars such as Vermes, Sanders, Crossan, Meier, Fredriksen, Theissen and Winter.

Murphy is right to point out that the Jesus who is the result of CDD is inevitably going to be nothing like the Jesus in the gospels and therefore will not serve as a doorway to the Christian faith.

Murphy discusses the reflections of another scholar I have also spoken about on this blog several times, Scot McKnight, and his conclusions: the way scholars inject their own personalities and theological views into their respective reconstructions of Jesus; and the suspicion that the motivator of such historians is not a disinterested curiosity about what really happened, but a desire to find an alternative Jesus to the one of traditional orthodox faith.

But Murphy rightly goes further than I have done in my discussions. He points out how even Scot McKnight’s conclusions and options for historical approaches go nowhere towards leading biblical scholars out of their theological blinkers. McKnight himself is prepared to accept a resurrection and heavenly ascent as a legitimate historical explanation, and hence is as unlike any genuinely unbiased historian as any of his colleagues. I agree. This sort of nonsense demonstrates the un-rational approach that finds a congenial home among the guild of biblical scholars. (This is not anti-supernaturalistic “bias”, but simple logic. A miracle must by definition always remain the least probable explanation no matter how unlikely various alternative natural explanations might appear to be.)

I particularly like Murphy raising the question whether New Testament scholars are the ones qualified to investigate the historicity of Jesus or Christian origins. Would not there be a case for mythologists, sociologists, comparative religionists, or historians being better qualified to study the historical origins of the movement?

So Murphy demonstrates that the scholarly approach (one that relies most heavily on CDD) does not get us anywhere nearer a historical Jesus. A historical Jesus is merely a hypothesis constructed to catch what cannot be explained by Judaism and the Christian tradition — and that omits the very mythical elements that really make the Jesus narrative meaningful.

The Christ Myth alternative not very different from the orthodox historical Jesus position

Christianity grew as a result of the shining faith of the early Christians; martyrs died for the Christ of faith, not the historical Jesus. This is, more or less, as Derek Murphy astutely observes, the position of both mythicists and historicists. Both agree that the mythical overlay eventually came to be understood as historical reality.

The reason for the debate, according to Murphy, is the refusal of academia to accept the possibility that comparative mythology can shed light on Christian origins, and their insistence on finding a historical Jewish Jesus. Yet the similarities of Jesus with pagan mythical figures has been recognized since the second century. Granted, as Murphy admits, that much past scholarship arguing for a mythical Jesus was bad by today’s standards, and “most” online supporters of mythicism have made little progress in this area.

On the other hand, Murphy makes the telling observation that scholarly arguments against mythicism also ignore much of the critical research of recent years in their own discipline. Arguments that were used against mythicism a century ago and that have long since been discredited as lacking logical foundation or as having been outpaced by critical research since, are still being dragged out by scholars intent on demolishing the very questioning of Jesus’ historical existence.

Related articles

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I did like McGrath’s claim that mythicism is so bad that it is not an argument that ‘historicists’ suffer from the same problems.

‘As long as mythicists seem to agree with one another on almost nothing except the ahistoricity of Jesus, please stop treating it as an argument for mythicism that historians agree on little apart from his existence.’

Can you imagine Dawkins claiming that because creationists cannot decide on something, mainstream scientists are excused producing a consensus?

Has McGrath spent much time on thought for that post?

McGrath claims mainstream consensus is overwhelming, so suck on that mythicists, and then his menu of answers claims that it matters not one bit that there is hardly any mainstream consensus, so suck on that mythicists.

Sorry but Doceticism cannot be compared to the claim that Jesus did not exist and is an assembled myth! Docetists still believed that Jesus walked around, said what he said etc…

Justin Martyr and Celsus’ discussions on similarities between Jesus and myth of course, as you intimate, do not have anything to do with claiming that the position that Jesus didn’t exist! Both believed Jesus existed. There is no line of scholarship or position that thinks Jesus did not exist. It is a modern and marginal position, no matter how much your author wishes to sooth this disturbing fact by making these tenuous appeals.

Certainly. I was once told that the people of Ireland believed that leprechauns really exist and walk around and talk and do things in this world, and some people even see them to verify the story.

Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, David are also said to have been historical by many Christians today.

My point is, as I have posted before, that when Paul says that Jesus was born of a woman yet was still the son of God himself, that he also may well have imagined Jesus appearing on earth, just like Heracles, Achilles and the Dioscuri.

At what point do we draw the line and say that someone is not historical? When they are entirely literary? When they are only half a human and half a god? When they are all apparition?

I think you are assuming that Docetists somehow must have believed Jesus did everything in the gospels — getting baptized, fasting, doing this and that miracle, teaching, feeding others — all as an apparition. I don’t think so. All references I am aware of pertain to the crucifixion only. (We are far from confident that even the authors of 1 John and the Ignatian epistles knew the gospel narratives.)

So these are questions your view needs to address. If you have answers, that’s great. Do share them.

But till then, do note my deliberate wording in the passage to which you object, and which reflects accurately, I think, what Derek Murphy writes:

I do appreciate your comment, even though you can see I disagree with its approach. It is one that has often been raised and that deserves to be addressed.

According to Bart Ehrman:

Ancient people also had a more nuanced sense of truth and falsehood; they too had stories that they accepted as “true” in some sense without thinking that they actually happened. Most scholars today recognize that the majority of educated people in ancient Greece and Rome did not literally believe that the myths about the gods had actually happened historically. They were stories intending to convey some kind of true understanding of the divine realm and humans’ relationship to it.

Neil,

I was only dimly aware of “mythicism” before I started reading your blog a year or so ago. I had only passingly read of Doherty through Carrier’s review of The Jesus Puzzle as I made my way through his articles on infidels.org, and didn’t think anything more about his ideas until I found your blog.

I have more recently pored over Doherty’s Jesus Puzzle website, and I have to say I am impressed with his overall argument. He makes sense out of unusual texts (Odes of Solomon, Ascension of Isaiah, etc.), and demonstrates convincingly that Paul’s Christ could be entirely mythical.

However, this doesn’t change my suspicion that “Jesus” still could have been “historical.” Paul’s “brother of the lord” reference to James may or may not be a title. Doherty does not entirely convince me that it is. Likewise with his argument that The brother reference in Josephus is an interpolation. Maybe, maybe not, is all I’m left thinking.

The bigger “problem” for me is the existence of the Ebionites. How can we explain their (admittedly sparse and questionable) belief that “Jesus” existed and was a man? And, to take it deeper (and which may be set aside for the moment), what about the Root of Planting in the Damascus Document or other possible DSS “references” to a messiah figure and seeing “Yeshua” (in the sense of salvation)? I don’t have time at the moment to outline all the relevant sources about the Ebionites, but this is the “big” issue that makes me wonder if “Jesus” might have existed, and I haven’t read anything of Doherty’s that adresses this.

Thanks for the reply Neill.

I rather think that trying to compare mythicism with docetism is an equivocation.The point that Docetists believed, that Jesus as divine could not be truly carnal flesh but must only have appeared to men as such, is different to the theories being espoused here. The only similarity is that you can say ‘was Jesus really a real man’… but mean ENTIRELY different things by it. Unless its making a rather facile point (that there have been disputes over the exact nature of Jesus) I don’t understand why it is included in this book then. It goes no way to supporting the claim of a line of theories or arguments over the existence of Jesus. If the author has suggested that it does he either doesn’t understand docetism, or is being misleading.But perhaps I should read his entire argument before making a definitive opinion on that.

Now on the separate issue where you suggest Docetists just believed in Jesus actions (or appeared actions) on the cross, this is, as far as I know, a new suggestion. Your right it is the cross where the Docetists most commonly articulate their views, and for that you should consult R. Goldstein and G. Stroumsa’s The Greek and Jewish Origins of Docetism: A New Proposal and Stroumsa’s Christ’s Laughter: Docetic Origins Reconsidered. But the idea that Docetism (and it isn’t a group by the way, its a persuasion, but I presume you are aware of that) didn’t hold to Jesus’ actions is, well odd. I dont know why you say: “I think you are assuming that Docetists somehow must have believed Jesus did everything in the gospels — getting baptized, fasting, doing this and that miracle, teaching, feeding others — all as an apparition. I don’t think so.”

Well we have records of pretty much everything you have just listed there coming from docetist beliefs. His Baptism (Haer) 1.26.1; coming to earth (Haer 6.1), nativity (Marc. 3.9.1), miracles (Haer. 2.32.4) etc…

Docetists would have no problem in having Jesus walking round doing these things- in fact that is what they believed! It also applies to other divine beings. For example the angels who appeared and discoursed with Job are accorded as being genuinely historical by Docetists but they are framed through their ideas of true essence.

As for John’s comments. Please keep looking. I would also be interested to find an example of any group or person from before the 20th century that believed Jesus didn’t exist.

Erlend: “I would also be interested to find an example of any group or person from before the 20th century that believed Jesus didn’t exist.”

You mean other than Dupuis, Volney, D.F. Strauss, Bruno Bauer, and the Dutch Radicals? Try this.

If you’re looking for people who argued against his existence in antiquity, I’d be surprised to find any. I’m unaware of anyone arguing that Mithras, Moses, Zoroaster, or Siddhartha didn’t exist. When a critic like Celsus lashed out at Christianity, it was far more useful to call the founder a faker, a charlatan, an immoral person, etc.

If casting doubts on existence was unknown for other cases (and we know that philosophers cast aspersions on other mystery cults and fringe religions), then why would we expect it for Jesus? I could be wrong of course; I’ve just never come across a case in which an ancient writer argued that some religious leader, prophet, or founder never existed.

Should we be surprised that this line of argument didn’t emerge until the Enlightenment?

Erlend, you haven’t looked very far — Bruno Bauer would be the proof in that pudding. But you can look in your Bible for proof from the 2nd century forgery of 2 Peter:

For we have not followed cunningly devised fables, when we made known unto you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but were eyewitnesses of his majesty.

If nobody thought that in the 2nd century, why would the forger of 2 Peter mention it?

Thanks for the pointers Tim and Evan.

Tim, Well no-one would make such judgement against Mithra for obvious reasons. The claims that were made about Jesus were entirely different. As for Moses, well perhaps they didn’t. Although we don’t have hardly any writings from Jews during the first few generations time that the story of Moses was added to scripture, and entirely different for Christianity. And the quest for parallemania was around in the 1st century. Perhaps you don’t know what some Jews started claiming that the stories of Moses were copied from Greek myths? I do have an issue with how a movement was apparently formed from an amalgamation of myths and mysticism, that this was then entirely forgotten. These are, of course, issues I know that can’t be discussed fully in a comment box so I wont try. I think it sufficient enough to point out that the only existence of the theory came almost two thousand years after Christ, despite the attention given to Christianity from those very people in the ancient world who should have been able to straight away pick up straight away the genre and purpose of these stories if they were.

Evan,

the claim from 2 Peter (found in 1:16) is a statement to do with the very purpose of the document where the author is arguing that Christ’s return is indeed going to happen, and that it is not a fable or something they made up. The entire document is pretty much stating this. I don’t know why you raise it with regards to whether Jesus was a myth.

Erlend: “Perhaps you don’t know what some Jews started claiming that the stories of Moses were copied from Greek myths?”

You’re correct; I’m not familiar with that. Do you have any sources I could check out? I’m aware of the persistent belief that other lawgivers copied Moses.

Erlend: “I think it sufficient enough to point out that the only existence of the theory came almost two thousand years after Christ, despite the attention given to Christianity from those very people in the ancient world who should have been able to straight away pick up straight away the genre and purpose of these stories if they were.”

Well, if you put any stock in the quote from Tacitus’ Annals, at least some people regarded Christianity as a “mischievous superstition.” One could argue that he’s specifically talking about the resurrection, but he doesn’t say that, and the simplest reading is that he regarded the whole story as superstition.

Similarly, Pliny the Younger calls Christianity a “contagious superstition.” But these external sources, along with the contaminated Josephus citations, betray a lack of any direct knowledge of Jesus or for that matter any first-hand witnesses.

And they don’t appear to be all that interested in finding out more — for them it’s sufficient to know that Christians have crazy beliefs and crazy practices. Moreover, since they denied the true gods, Christians threatened the pax deorum. If you’ve ever played Caesar III or IV, you know you don’t want do do that!

We should recall, by the way, that it wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that scholars came up with the Two Document Hypothesis and “discovered” Q. Sometimes it just takes awhile to figure things out.

Erlend, are you suggesting that Jesus’ power and majesty are historical facts that the author of 2 Peter was referring to? Your explanation smells a bit of apology. In addition, Justin is quite clear that the story of Jesus is in the same category as that of Hercules and the Dioscuri — stories which were not believed to be literally true by the ancients.

Evan,

Its not apology. Read 2 Peter and you should see exactly what these comments are alluding to. Its what every commentary from every strain of Biblical scholar you can find will say. To be sure I consulted Rebecca Skagg (2004), Edward Adams (2005), Anne Ruth Resse (2007). Ehrman’s Forged probably will go into this. You are the first person I know of to think that Peter diverts his discussion on his opponents accusations against the eschatological promises of Christianity to allude in one verse (and then say nothing else about it) their lack of faith in the whole presented narrative of Jesus’ life. The references to power and majesty are tied at with the paraousia.

As for Justin he evidently did believe that his opponent did believe their myths. He opens the section you are referring to as ‘you believe that x did this…’. Also, Justin whose apologetic strategy is to show Christianity is in continuity with Greco-Roman beliefs, that they should be persecuted for their beliefs aren’t as idiosyncratic to the Roman world. Here, for a just few lines he makes some very tenuous connections trying to show the similiarity between Christianity and Greco-Roman myth. When you understand the context and purpose of Justin’s comments it really takes away a lot of the heat that some mythicists want to try to create surrounding it.

Erlend, as you can imagine, it is possible that every strain of Biblical scholar can be wrong. I have read Ehrman’s Forged and it does not include a discussion of this. What I invite you to do is read all of 2 Peter. It’s clearly a forgery written by a late proto-Catholic author who was trying to calm the disputes between the Pauline and Petrine factions in the second century Christian church. He repeatedly argues against people who do not believe the Christ myth literally happened. Read the whole text:

In chapter 1 verse 18: “we ourselves heard this voice that came from heaven while we were with him on the sacred mountain.”

The author of this letter is lying, of course, as he was never on the sacred mountain with anyone. Therefore, his earlier statement that he didn’t follow cleverly devised stories is made an even bigger lie, since he is lying to create the impression that he was an eyewitness to something he wasn’t. Why would a Christian lie so blatantly? He is clearly trying to prove that the entire Jesus story is literally true, in the face of others who argue that it was a myth — as Ehrman notes in my above quote, the ancients were quite sophisticated and didn’t believe their myths had literally happened.

Then in verses 19 and 20, he tries to show that it is wrong to point out the meaning of Hebrew scriptures and explain that the story of Jesus doesn’t fulfill their prophecies (Marcion) and that they were in regard to different things, because only God knew what was going to happen, therefore one cannot trust the interpretations of the Jews to understand the Hebrew scriptures.

Then chapter 2 verse 1 gives the whole game away:

“But there were also false prophets among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you. They will secretly introduce destructive heresies, even denying the sovereign Lord who bought them—bringing swift destruction on themselves.” Here again we have a reference to people who claimed to be Christians, but viewed the Jesus story as a myth. The forger then heaps calumnies upon them for the rest of the chapter.

Finally chapter 3 verse 3 again admits that there are people who do not believe in the story of Jesus and they are called “scoffers.” They deny the second coming, but clearly they also deny the first by “deliberately forgetting” that the Logos made the heavens and earth.

The author’s opponents aren’t around to speak for themselves, and Ehrman is even a bit confused about what they might have said, stating that the author is never exactly explains what they taught, but it is clear that they did not believe there had been a Logos on earth — the central contention of 2nd century proto-orthodoxy.

Thanks for the reply Tim.

The section from Philo comes from his Confusion of the Tongues.

Im open to considering the Christ myth,and your right, it the theory cannot be discounted just because we have no evidence of any awareness of it from antiquity. It is something I think I would always have some disquiet about though, which I think it fair. But then any position on this issue will have problem areas…

Hi John, Erland — Miscellaneous responses follow:

The significance of Derek Murphy’s reference to Docetism in the contex of mythicism is clearer in chapter 3 of JPHC which I will be covering soon.

I personally see it as much more significant than I originally did when first looking at the Christ myth arguments. If we are looking for a direct correspondence of concepts then and today we won’t find it in Docetism. But the significance of Docetism hits me when I try to understand how a normal historical life could so quickly generate views that Jesus was not a human at all. If we are working with a model that begins with eyewitnesses and oral traditions within the generation of those eyewitnesses, then I think we would be facing something unique if a widespread belief emerged so soon that that person was not in any sense human (except in appearance). (Maybe there are other examples so if there are I’m sure I’ll be shot down for that statement.)

The gospels themselves – in particular Luke – are seeking to rebut the idea that Jesus was not human or flesh, even after his resurrection.

The existence of Docetism so early in the piece makes more sense as an early attempt to bring a heavenly Christ to an earthly setting, and then the gospels that seek to establish the real earthly nature of Jesus are best explained as a development to solidify an alternative chain of authority beginning with a stable moment in history with real persons. The alternative till then, if Paul is any guide, had been visions given to this or that apostle. This also explains the gospels stressing that the earthly existence of Jesus was unrecognized in his own time except by a chosen few. All this makes sense as a polemic against a pre-existing view that Jesus was not really human.

As for phrases like “brother of the Lord”, much is made of these by critics of mythicism. But these criticism lack awareness of the case for mythicism and seem to think it is basically a matter of proof-texting. Hence they seem to think all they have to do is throw back their own proof-texts to rebut the case.

But for those who have looked into it seriously are aware that the case is not so superficial at all. When a case is made that is built on a substantial reorientation of learning to read the epistles without being influenced by “the tyranny of the canonical gospels”, and even when we read the gospels through the same orientation as we analyze other ancient texts, then phrase like “brother of the lord” and “born of woman” appear in one or two cases to be anomalies. The argument for mythicism is too substantial to be tossed by a few apparent anomalies. So we need to ask what explains those texts as anomalous. Is it our own lack of understanding of something? Are we justified in suspecting textual corruption?

As for the Ebionites, a question I would like to refresh my memory on is the dating of when we have the earliest evidence for them.

Is the tradition that they can be traced back to the time of fleeing Jerusalem and settling in Pella etc substantiated or is this a myth that serves the interests of both them themselves and even of the “Catholic” fathers who found it a convenient support for their version of church history as we read in Acts?

I find the notion of fleeing to Pella a little odd — how does one manage to do that when surrounded by Roman armies everywhere?

That term, “brother of the Lord,” hit me again this week as I was reading Ehrman’s Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene.

Just as an aside, I was hoping I could get some insight as to how Bart decides what’s historical and what isn’t. He’s extremely (and rightly) critical of later writings that purport to document the acts of the apostles or that pretend to be written by Peter. However, he continually reserves judgment on documents that are the oldest we possess. It’s the fallacy of treating the earliest evidence as primary evidence. He knows the gospels are late. He admits the gospels contain no real eyewitness accounts. He knows they’re anonymous and of unknown origin. He knows all this, but he still thinks they’re special because they come from the first century or slightly later.

I’m sorry to digress even further, but this is a point that the historicist defenders like McGrath keep disunderstanding. He writes in his now infamous list:

#6. If one disqualifies literature as a possible source of historical information, then one must treat Socrates, John the Baptist, Paul, and a great many other figures in the same way as Jesus.

It’s so easy to set up straw men and knock them over, isn’t it? Whoever said that literature is disqualified as a possible source of information? Nobody I know. The question is this: Does that piece of literary evidence have any corroborating data that leads you to believe that it contains actual historical information? Caesar’s Commentary on the Gallic War contains lots of pro-J.C. propaganda. But we also know it’s useful, since we have every reason to believe it contains real primary evidence.

Sorry to get so far off track, but that crap really bothers me.

Back to Bart’s book on Peter, Paul, and Mary. He writes that one of the things we “know” is that Peter had a wife and that she traveled around with him. She did? Bart cites 1 Cor. 9:5 —

Have we not power to lead about a sister, a wife, as well as other apostles, and as the brethren of the Lord, and Cephas?

I agree with Crossan and others that the Paul is referring to sister-wives, women who accompanied the itinerant apostles as celibate helpmates or “wives-as-sisters.” It’s interesting to see that most modern translations hide any hint of this by using the term “believing wife.” Notice that they’re assuming ἀδελφὴν γυναῖκα (sister wife) has nothing to do with blood ties or with some kind of social relationship. Here, sister means “believer.”

But in that same sentence we have ἀδελφοὶ τοῦ κυρίου (brothers of the Lord), and in this case it’s translated literally, and generally understood to refer to Jesus’ blood brothers. I think it’s worth asking whether the reference to James as “brother of the Lord” and these itinerant preachers with sister-wives had something to do with an official standing within the early Jerusalem church. It is by no means a far-fetched idea, since “brother” and “sister” were terms used to describe both religious affiliation and blood ties.

McG. again: “Fundamentalists and mythicists enjoy exploring all the possible meanings of words like ‘flesh’ and ‘brother,’ but within sentences and specific linguistic and grammatical constructions, constraints are placed on meaning.”

Hence, in the case of 1 Cor. 9:5, sister does not mean sister, but brother does mean brother. Of course! Are you blind? Now sit down and shut up.

Hm, just a thought, if Paul’s reference to James as THE brother of the Lord is a title, denoting his being the highest standing brother of them all, as Doherty siggests, I wonder if anyone else was THE sister of the Lord? Just a playful thought.

It’s also possible the synoptic tradition that says everyone who does the will of God is Jesus’ brother, sister, and mother is a muffled polemic against the idea of an inner circle of “The Lord’s Brothers.”

Mark 3:35 — For whoever shall do the will of God, the same is my brother, and my sister, and mother.

We tend to read that now as Jesus’ response to the rejection by his family. But perhaps the logion’s original purpose was simply to universalize religious-familial ties to Jesus. In other words, “You are all my brothers and sisters, not just those stuffed shirts in Jerusalem.”

Tantalizing. If only we had more evidence.

Arousing desire or expectation for something unattainable or mockingly out of reach…

I have received enough feed-back over the months to lead me to think anyone with an open mind looking into both sides of the question can see how McGrath unfairly distorts certain arguments and statements.

Neil,

You are asking fair questions. I will need to address them one at a time, due to space considerations and the amount of homework that is necessary to answer them.

On the question of the earliest references to the Ebionites, they are generally by the usual grab bag of second century church fathers people turn to to find the earliest evidence for the existence of the canonical gospels, the earliest possible being Justin Martyr and the most definite is Irenaeus: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Ebionites_according_to_the_Church_Fathers

There is also the evidence of the heretic Cerithus (c. 100?), who was arguably influenced by Jewish Christians: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerinthus

That there would be gentiles like Ceritnhus is not surpising considering the evidence that Gentiles joined the Jews of the Dead Sea Scrolls sect, whom they refer to as “joiners” (nilvim, or ger-nilvim; e.g., in the Damascus Document, col. 4).

However, as you know by now, I follow Eisenman and he goes deeper than this. There is evidence in the letters of Paul and James that James’ group was known as the poor:

“James and Cephas and John, who were reputed to be pillars … they would have us remember the poor,” (Gal. 2:9-10); “For Macedonia and Achaia have been pleased to make a contribution for the poor among the saints of Jerusalem” (Rom. 15:26).

“Has not God chosen those who are poor in the world to be rich in faith and heirs to the kingdom which He has promised to those who love Him? (James 2:5).

The Dead Sea Scrolls sect also referred to itself as the poor:

“Interpreted, this [verse] concerns the congregation of the poor [ebionim], who [shall possess] the whole world as an inheritance,” (Psalm 37 Pesher col. 3 Vermes).

“As he himself [the Wicked Priest] plotted the destruction of the poor [ebionim], so will God condemn him to destruction,” (Habakkuk Pesher col. 12 Vermes).

The letter of James, genuine or not, is rather antagonistic to the rich: “But you have dishonored the poor man. Is it not the rich who oppress you, is it not they who drag you into court? Is it not they who blaspheme the honorable name which was invoked over you?” (James 2:6-7); “Come now, you rich, weep and howl over the miseries that are coming upon you … Your gold and silver have rusted, and their rust will be evidence against you and will eat your flesh like fire. You have laid up treasure for the last days. Behold, the wages of the laborers who mowed your fields, which you kept back by fraud, cry out; and the cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord of hosts. You have lived in pleasure; you have fattened your hearts in a day of slaughter. You have condemned, you have killed the righteous man; he does not resist you. Be patient, therefore, brethren, until the coming of the Lord” (5:1-7).

Interestingly, Jospehus mentions that at the beginning of the war with Rome, the sicarii “set fire to the house of Ananias the high priest [the priestly family that had James murdrered!], and to the palaces of Agrippa and Bernice [who were so chummy with Paul in Acts!] , after which they carried the fire to the place where the archives were deposited, and hurried to burn the contents belonging to the creditors, and thereby dissolve their obligations for paying their debts; and this was done in order to gain the multitude of those who had been debtors, and that they might persuade the poorer sort to join in their insurrection with safety against the wealthy,” (War 2.426-428).

That this uprising of the poor against the rich was also MESSIANIC is confirmed by Josephus, who says that, “[W]hat did the most to elevate them in undertaking this war was an ambiguous oracle THAT WAS ALSO FOUND IN THEIR SACRED WRITINGS, how, about that time, one from their country should become governor of the world,” (War 6.312).

This is the kind of oracle that we find in the Dead Sea Scrolls: “Thou hast taught us from ancient times, saying, ‘A star shall come out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel’ … By the hand of Thine annointed, who discerned Thy testimonies, Thou hast revealed to us the [times] of the battles of Thy hands that Thou mayest glorify Thyself in our enemies by levelling the hordes of Belial [a term familiar to Paul] … by the hand of Thy poor whom Thou hast redeemed (by Thy might),” (War Scroll col. 11 Vermes); and, “The sceptre is the Prince of the whole congregation, and when he comes he shall smite all the children of Seth” (Damascus Document col. 7 Vermes).

Josephus also describes the insurgents as innovators who introduced new doctrines into Judaism, also like the “Ebionites” in the Dead Sea Scrolls, who referred to their practices as “the New Covenant in the Land of Damascus.”

There are just too many parallels for me to ignore the possible connection with the Dead Sea Scrolls “Ebionites” and those that the church fathers mention in the second century. Add to these undeniable parallels the strong similarity of the Wicked Priest who murdered the Teacher of Righteousness with that of the priest Ananus who murdred James, and the Spouter of Lies who opposed the Torah and the Teacher of Righteousness with the person of Paul, there is not a doubt in my mind that what we have in the Dead Sea Scrolls are the writings of first century Ebionites.

Now, as for your second question concerning whether or not the Ebionites could have escaped the Roman army and flee to Jordan, as Eusebius mentions (if he’s even right about it), that should be dealt with some other time, as it is a separate issue.

Sorry but I still fail to see how the references to the poor in the NT relate to a title or name of a sect. They always seem to be referring to an economic subgroup within the sect.

And once we deal with the questions arising over that awkward Christ reference in Josephus’ discussion of James and his murder, I don’t know if we have any reason to think of this James as having any relation to the disciples of Jesus. (At the risk of sounding perverse, I do sometimes wonder if that famous trio of names, James, Peter and John, are later inventions created to establish a foundation of alternative genealogical tree of authority from Jesus to later leaders of a particular brand of Christian movement.

Maybe Eisenman has answers for all of this, and I admit I have yet to read Eisenman in full.

My responses are in haste — traveling outside Australia again and away from my books and with limited internet access. I should add that many years ago when I was a member of a cult that liked to think of itself as a spiritual descendant of the Ebionites, I did encounter a number of papers making suggestions linking various NT passages about the poor to the name of the Ebionites. I later came to reject all such links and felt the arguments had been self-serving.

I thnk this was a case of me not expressing the proposition well. It would be better to say that James’ group were known for being poor. Ebionite was certainly not a title in the first century, any more than Sicarii, Zealots, or even Essenes were. These were words other people used to describe them. Eisenman sometimes calls them Messianic Sadducees. Ebionite was one of many self-references in the Dead Sea Scrolls that bear a similarity with designations in the NT, like the Way (derekh), the meek (ani), the downtrodden (dal), the Sons of Light, the holy ones (hasidim), the perfect (tam), the New Covenant, and additional ones like the Sons of Zadok and the simple of Judah doing Torah, and “both” sects were located in a place called “Damascus.”

Ebionite as a “title” may have been something that happened by the second century, judging from the observations of church fathers, but again, even then it was still the observation of outsiders. We are left with these similar references in the Dead Sea Scrolls of a sect very Jamesian-like, and additionally a similar group history, in that both James and the Teacher of Righteousness are both refered to as the Righteous One (zaddik), both suffer the same fate (a trial and death at the hands of a “wicked” priest), and contended with someone who rejected the Torah and founded their own congregation on “lies.” This is too much coinicidence for me to dismiss so lightly.

Clarification: I don’t mean “so” lightly as directed you. I only mean “to dismiss lightly.”

Neil,

These two links save me a lot of work and summarize well the arguments for and against the traditon of the Pella flight, including how Ebionites could have escaped the Roman armies (after the destruction of the first Roman legion in 66 CE, which gave the revolutionaries hope, or during the Vespasian’s pause in military action after the death of Nero in 68). I don’t know what to make of the tradition, though it’s not implausible.

http://web.archive.org/web/20120927174450/http://www.preteristarchive.com/JewishWars/articles/1998_scott_flee-pella.html

http://www.rejectionofpascalswager.net/pella.html

Why would the Ebionites have only been in Jerusalem anyway? I think anyone who thinks that there were no Ebionites outside of Jerusalem to begin with must be pretty stupid. The church fathers talk about Ebionites as existing well into the 4th century, so any theory that “oh, the Ebionites only existed in Jerusalem and they were all wiped out in 70” is pretty stupid. The Ebionites weren’t wiped out by the Romans in 70; they were wiped out by the Roman Catholics over the next few centuries.

The problem with the Christian position is that accepting that the gospels are accurate history about Jesus also comes with the baggage of accepting that everything else in the Bible is accurate history. If you accept that Jesus is literally the Son of God incarnate, you have to also accept that King David had 3 super-soliders in his employ who were each capable of taking on entire armies by themselves without being injured, that Samson was literally turned into superman when his hair was long, and so on. Because to believe any less than everything the Bible says is called “heresy” by the fundamentalists. They preach about faith alone, faith in Jesus’ death alone, but that’s just a bait-and-switch to get you to come to church so they can indoctrinate you in the rest of their mythology.