A standard formula-problem found in historical Jesus works is that the question that needs to be explained is how or why Jesus’ disciples were able to persuade so many Jews that a crucified criminal was indeed the Christ. And of course, to explain why the disciples became convinced of this themselves.

These are indeed extremely improbable scenarios.

One “biblical scholar and historian” who is also a Christian writes:

As we have already seen, what precisely motivated [the disciples] to believe that Jesus had been raised . . . is difficult if not impossible to say from a historian’s perspective. (The Burial of Jesus: History & Faith, p. 121)

And again,

There seems to be little hope of gaining access by means of the later written sources to the actual experiences that early Christians had, the ones that convinced them Jesus was alive. Even Paul only alludes to his own direction-changing experience, and never describes it. Perhaps this is appropriate: religious experiences are regularly characterized by those who have them as ineffable, as “beyond words.” The Gospel of Mark suggested that Jesus would be seen, but doesn’t describe the experience, at least not in our earliest manuscripts. . . .

But this much can be said: the act of completely surrendering has transformed many lives. Such unconditional surrender to God seems to have been central to Jesus’ own spirituality. There would be something fundamentally appropriate if it turned out to be central to the rise in the earliest disciples of the conviction that Jesus had been raised, as it has been for Christians all through the ages since then. (pp. 115-116)

This historian is writing for his fellow-faithful. In doing so he has given away his bias that would seem to preclude him from any ability to continue his historical enquiries until he finds a truly historical explanation for the rise of the Christian faith. He is content with an explanation that opens up room to find his faith — the inexplicable, even the ineffable — in history. (And given that this particular faith is dependent upon historical events, Schweitzer’s pleas notwithstanding [- see below], this is surely an inevitable conclusion for a committed Christian.)

This is not good enough for truly post-Enlightenment historiography. History is often enough defined as an investigation into what is human, what can be naturally explained.

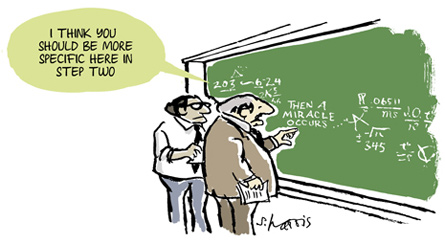

If our questions and models bring us up against a brick wall of “ineffability” then it is time for historians to ask new questions and try new models until they do find the natural and explicable answers.

The Gospel narratives, particularly that of the earliest Gospel of Mark, make no sense as history. Read naively they prompt silly questions like: Why did Jews come to believe a crucified criminal was their messiah? Such silly questions are embraced with utmost sober seriousness presumably for the same reasons they were a subject of boast by Tertullian: “I believe because it is absurd.”

They are questions grounded in faith and therefore also supportive of faith. Even non-Christian scholars embrace them because the faith narrative has become part of our very cultural identity.

The historian who is prepared to set aside assumptions and hypotheses that have been found wanting, or that are self-authenticating being found exclusively within the Christian narrative itself, will necessarily be operating from the cultural fringes. But that is the only historian who is likely to stumble upon an answer to the real historical question (how did Christianity begin?) that is completely natural, human and explicable of all the evidence. There will be no need to be content with “the ineffable” or “difficult if not impossible to say” in place of an explanation.

Granted, not all biblical historians do accept the unknown or “impossible to say” in place of a genuinely historical explanation. But they do still work within the culturally rooted paradigm and are up against a model that has more to do with faith and myth than with human reality. This explains why there is so little in common, and much that is mutually exclusive, among the many Jesus reconstructions by biblical historians working within the constraints of the model that remains an inheritance of faith. The wildly opposing results generated through their paradigm ought to suggest a new paradigm and new questions are timely. But how to begin with something that is so much a part of our collective identity?

And once again, as quoted here before:

Moreover, in the case of Jesus, the theoretical reservations are even greater because all the reports about him go back to the one source of tradition, early Christianity itself, and there are no data available in Jewish or Gentile secular history which could be used as controls. Thus the degree of certainty cannot even by raised so high as positive probability.

. . . Modern Christianity must always reckon with the possibility of having to abandon the historical figure of Jesus. Hence it must not artificially increase his importance by referring all theological knowledge to him and developing a ‘christocentric’ religion: the Lord may always be a mere element in ‘religion’, but he should never be considered its foundation.

To put it differently: religion must avail itself of a metaphysic, that is, a basic view of the nature and significance of being which is entirely independent of history and of knowledge transmitted from the past . . .

From pages 401-402 of The Quest of the Historical Jesus, 2001, by Albert Schweitzer.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“Impossible to say” is not a reference to something ineffable or miraculous, but to a lack of reliable information. Historians are confronted with that situation all the time.

1. There is a difference between “impossible to say” because of lack of evidence and “impossible to say” that involves the acceptance of implausible and unnatural scenarios.

2. If this problem Jesus scholars are faced with is something endemic among historical explanations, what are some examples you would consider comparable to this Jesus question?

3. If one paradigm throws up “impossible to say” as a conclusion and another seeks and finds what is possible to say . . . .

I don’t see how a historian who aspires to any degree of objectivity can say things like “the act of completely surrendering has transformed many lives. Such unconditional surrender to God seems to have been central to Jesus’ own spirituality.” Why should the conversion experience of Christians be considered any differently than that of Mormons, Scientologists, Muslims, or the poor gullible fools who followed Jim Jones down to Guyana?

Neil, in the context I was clearly discussing a situation in which we simply don’t have the evidence we’d like. If we had early descriptions of dreams or visions that led to belief in Jesus’ resurrection, we might still be skeptical. But we don’t even have that. We have Paul saying Jesus “appeared” in 1 Corinthians 15 but there is no indication of any details that might indicate the nature of the experience. And our earliest Gospel has no account of resurrection appearances in the earliest form in which we have it either.

Vinny, who said that the conversion experience of Christians ought to be considered different from that experienced by people in other religions?

I understand the context in which you were writing, and I hope I did not misrepresent you. If there is something specific in what I said that you feel is a misrepresentation let me know and I will make the appropriate adjustments.

Dr. McGrath it seems pretty clear to me. Your argument is that the Jesus of history died and then his believers became convinced that he had been resurrected. This was their conversion. This was when they unconditionally surrendered to God. Your apparent belief (as is the mainstream explanation of the rise of Christianity) is that their conversion experience — experience the historical Jesus as resurrected, led to the genesis of the Christian religion.

Yet nobody gives the conversion of multiple members of the LDS church in the 19th century as weight for the existence of historical plates of gold in the hand of the angel Moroni except for other members of the LDS church. I am not aware of mainstream LDS historians arguing that the explosion of the LDS church vindicated claims of historicity for the golden plates.

This seems to me the point Vinny is making. He can correct me if I’m wrong.

And I in no way suggested that a religious experience can tell us something about historical events.

I think determinations that lives have been transformed by “unconditional surrender to God” are inherently faith based rather than the product of historical inquiry. The historian can observe that members of the People’s Temple embraced Jim Jones as a prophet, moved to Guyana with him, and committed suicide upon his command. However, it would be ludicrous for the historian to assert that their actions were the product of surrendering to some supernatural power rather than the result of accepting the authority of Jones.

A perfectly logical explanation is available in a natural phenomenon that has been observed to occur repeatedly throughout recorded history, i.e.,silly gullible people who want to believe in a supernatural meaning for their lives are taken in by a charismatic leader who fills their heads with fantastic stories and ideas that he claims were revealed to him by God. It may be possible to identify the sources that influenced the stories and ideas, but there is nothing about the phenomenon that requires there to have been any historical people or events behind them.

But presumably we can talk about the existence of Jim Jones, and to the extent that we have information about them, the beliefs of his followers. That people are prone to delusion doesn’t show that the deluders and the deluded didn’t exist – I hope you’d agree!

We can talk about it, but if one of us has a faith based commitment to the proposition idea that the Jones’ followers had a unique spiritual encounter that worked upon them some inner transformation, while the other is guided by empirically derived conclusions about religious manias drawn from the fields of psychology and sociology, we are going ask different questions and weigh the evidence differently.

Take for example the question with which Neil began his post: how or why were Jesus’ disciples able to persuade so many Jews that a crucified criminal was indeed the Christ? To a large extent I think that question is beyond historical investigation. There might be enough information about the members of the People’s Temple for a psychologist or sociologist to venture some credible explanation of how these people came to be taken in. I suspect that there is not enough data about the people who were taken in by Joseph Smith to do more than guess what was going on in their heads. However, going back 2000 years seems ridiculous. We have next to no data about the Jews who believed and little more about the Jews who convinced them to believe. I don’t see how the historian can say much more than “People are prone to believe crazy stuff.”

Dr. McGrath, are you suggesting that we have 1% as much historical information about Jesus of Nazareth as we do about Jim Jones?

‘As we have already seen, what precisely motivated [the disciples] to believe that Jesus had been raised . . . is difficult if not impossible to say from a historian’s perspective.’

What the guy needs to do is read the work of historicists, as they have produced the best explanations of how a crucified criminal came to be regarded as the Messiah.

Many studies have been published on cult indoctrination and why people are persuaded to join cults. We have both psychological studies and sociological studies. (And we can even say we have “historical” studies, even back to the millennial movements in the Middle Ages, though these are often overlapping with models from sociological studies.)

Why people join Jim Jones and other cults is perfectly explicable in psychological, sociological and historical senses. We can’t explain the motives of every individual, but we don’t have to. The fact that a diary of a Russian revolutionary informs us that one particular person joined the cause for personal reasons having to do with love and personal affections does not change the general historical explanation for the rise of the revolutionary movement.

But we can’t explain why Jews would, by their thousands, believe in a fellow mortal being their worshipful heavenly messiah after his crucifixion as a criminal.

This “fact” makes no sense in historical or natural human terms. Does it not require revision if we are to subject Christian origins to genuine post-Enlightenment historical investigation?

Have not a few biblical historians attempted to revise this “fact”?