Tryggve N.D. Mettinger, Professor Emeritus of Hebrew Bible at Lund University, Sweden, takes issue with the “near consensus” (in the wake of J. Z. Smith’s assault on Frazer’s work) that ancient “dying and rising gods” do not really return from the dead or rise to live again.

Since I made reference to Baal in this death and resurrection context in a recent post, have decided to summarize here Mettinger’s reasons for arguing that Baal in Ugaritic mythology did indeed die and return to life again. Mettinger’s book is The Riddle of the Resurrection: “Dying and Rising Gods” in the Ancient Near East (2001).

Not having access to scholarly texts of translations of the myth I can only repeat Mettinger’s case (pp.57-66). There is an online translation of the Baal Cycle here that one can read for comparison with what follows. To find the relevant section of that translation search the words “As Baal went into the midst of the house” and start from there. (Be warned of name variations, though: Mot there is Mavet, etc.)

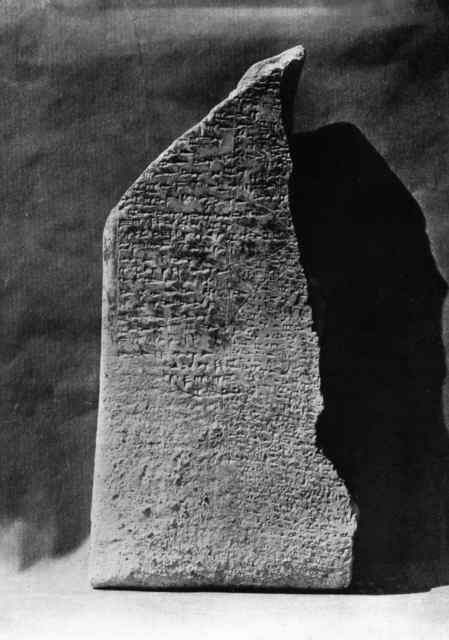

image from http://i-cias.com/e.o/can_phoe_rel.htm

Outline of the Baal-Mot myth

After Baal installs windows in his palace, he sends messengers to Mot (=Death)

The messengers are to go down to the House of Freedom and be counted among the dead

The message Baal gives them to take is not clear, but Mettinger believes it is: “I alone am the one who can be king over the gods, who can fatten gods and men, who can satisfy the multitudes of the earth!”

The messengers return to Baal with descriptions of Mot’s appetite and an invitation for Baal to descend to the Netherworld

Baal responds to this quickly and submissively: “Your servant I am, and yours forever”

Mot renews his invitation: “And you, take your clouds, your winds, your bolts, your rains . . .”

On hearing this Baal decides to beget descendants. He mounts a heifer and begets offspring.

[a gap of about 40 lines at this point]

Baal’s death is announced to El (the highest god) and El mourns for him

Mourning rites by El and Anat (Baal’s sister/consort) are described in detail

Anat and Shapsh (=Sun) search for Baal

They find his dead body at “the edge of the earth (a reading Mettinger takes from Smith in Ugaritic Narrative Poetry (1997), the limits of the waters, the pleasant land of the outback, the beautiful field of Death’s realm

Shapsh helps Anat carry the body to Mount Sapan where Baal is buried

Anat reports to El and Athirat that Baal is dead

El and Athirat discuss a replacement for Baal

Athtar is chosen to replace Baal but he is no match for the role

Anat decides to confront Mot directly

She seizes the hem of his garment and begs he release Baal to her

Mot tells Anat how he swallowed Baal

Anat reacts by giving Mot a hard time:

With a sword she splits him

With a sieve she winnows him

With a fire she burns him

With millstones she grinds him

In a field she sows him

El then has a dream-vision (oil and honey “rain” down to restore the richness of the earth) which he believes is informing him that Baal has returned to life

The decisive sign of this was the beginning of the autumn rains

On El’s behalf, Anat tells Shapsh that the furrows in the field are still parched

Shapsh promises to seek Baal

Finally, there is a description of Baal’s return to his throne

Then follows what seems to be a new conflict between Baal and Mot:

Baal and Mot are engaged in a battle for supremacy “in the seventh year”

Shapsh intervenes

Mot capitulates: “Let Baal be enthroned . . . .”

There follows a passage about Shapsh ruling the Rephaim

image from http://einhornpress.com/jews.aspx

Not a substitute but Baal himself

Where the 40 line gap appears it has been suggested that here Baal swapped places with a twin-brother. This twin went down to Mot instead, thus cheating Mot. The lesson is that the gods do not die.

Mettinger, however, responds that it seems none other than Baal himself did die. The evidence is in the damage done to the vegetation and the rain at the news of his death. Since Baal was the one responsible for these, it must have been he himself that descended to the realm of Mot, and not a substitute. Mot had called on Baal to descend with his “clouds, winds, bolts and rains”. After he had built his house it was announced that Baal would be able to appoint the times of his rains. (Compare the text on the piney site starting from “As Baal went into the midst of the house”.)

Finally, it is El’s dream of renewed rain that is the sign that Baal himself is alive again.

Shapsh, the torch goddess, in helping in the search for Baal, scorches the earth. Summer heat prevails in the absence of rain.

Mettinger is thus convinced that it Baal himself who goes down to Mot.

How could Baal have descended into Mot’s realm below the earth if his body was found on the margins of the habitable world? Mettinger points out that the descent is “a metaphor for death: humans go to the Netherworld and leave their bodies behind.” Similarly Mesopotamians sometimes spoke of the Netherworld being directly underground yet also located in the mountains in the northeast. Compare Burkert’s observation about Greek mythology (1985) that, “Contradictions are freely tolerated; sometimes, as in the Odyssey, the kingdom of the dead is located far away, at the edge of the world beyond Oceanos, and sometimes, as in the Iliad, it lies directly under the earth.”

Baal: Through Death to Life

The place

Anat found Baal’s corpse “somewhere at the margins of the civilized world: the edge of the earth, the limits of the waters, the pleasant land of the outback, the beautiful field of Death’s realm.” (p.61)

The same geographic description is used of the place where Baal mounts the heifer to produce offspring.

Mettinger takes these geographic descriptions (of both the place where Baal mounted the heifer — I can imagine what google searches would do if I expressed it more colloquially — and where his body was found — though after 88 + 77 mounts it is understandable that it was the one and same place) — Mettinger takes these geographic descriptions as references to the outskirts of the earth, not to the Netherworld itself. But explains: “The list is nothing other than a series of euphemistic metaphors for the desert and steppe as regions where civilization and the Netherworld meet. Baal is here found to be in a liminal zone, one with close affinities to Mot’s realm.” (Mettinger cites Pope, 1977 and G.A. Anderson, 1991, here).

Mettinger then points to other passages where it is clear that Baal was thought to have made a real descent into the Netherworld. Mot invited him to take his clouds etc and descend:

Head off for the mountains of my covert,

Lift up [one] mountain on [your] hands, [one] wooded hill on [your] palms,

Then go down into the place of seclusion [within] the earth,

you must be counted among those who go down into the earth

And the gods will know that you are dead.

Also in Mesopotamian literature (e.g. the Gilgamesh epic) the mountains are a motif for the entrance to the Netherworld.

Mot’s mouth is described as monstrously huge, large enough for Mot to be able to tell Anat that he swallowed Baal. This passage is followed by the drought formula.

Mettinger also notes that “the lexeme mt, ‘to die’, is used frequently about Baal” (p.62) in this section of the epic.

The reaction of the other gods

Further, the reaction of the other gods clearly indicates Baal is dead:

- El and Anat perform mourning rites, described at length.

- Both El and Anat say that Baal is dead and that they will descend after him to the Netherworld.

- Anat and Shapsh carry Baal’s corpse to mount Sapan, bury him and perform funeral sacrifices.

- This is followed by El deciding that Baal must have a successor.

- Athtar is chosen as Baal’s successor but is found inadequate.

We have thus mourning, burial, funerary sacrifices and a successor. “Baal is dead!”

The role of Shapsh

- Her scorching heat is due to the power of Mot, according to the drought formula.

- Every night she travels through the Netherworld, passing every sunset by Rashap, her gatekeeper.

- She is the all-seeing one who scales her orbit every day, and who also knows the Netherworld every night.

- She is also the psychopomps, the conductor of souls.

Shapsh is thus the ideal companion for assisting Anat in her search for Baal.

Her involvement in the events indirectly confirms that Baal is in the power of Mot, the god of the Netherworld.

The structure of the composition

The section beginning with Mot’s invitation ends with El’s dream about the coming of the autumnal rains. “These rains are the reliable sign that Baal is no longer dead but “lives” and “exists”.

“Thus the basic contrast in the Baal-Mot conflict is that between death and life. Baal’s “life-span” describes the sequence life-death-life.” (p.63)

Conclusion: Death and Resurrection of Baal

“The general thrust of the Baal-Mot myth must thus be taken to depict Baal not only as a dying god but also as one who returns from the Netherworld, and indeed resumes his royal power. . . The myth thus contains the mythemes both of his death and of his return or resurrection.” (p.63)

This is not the entirety of Mettinger’s discussion, and I have omitted many of the footnote supporting reference notes related to the section above. But it presents the main thrusts of his argument that Baal was indeed a dying and rising god.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

You should check out my paper: Who did Jesus call for?

Read it here: http://tao4all.wordpress.com/2008/07/15/who-did-jesus-call-for/ –It is the baalim, no doubt about that!

You make some interesting points. Just to comment on one in particular here, scholars who talk to each other in scholarly journals etc are doing so largely as a result of the way institutional academe works. The same happens in the hard sciences and history, but the difference is that some of those have excellent popularizers of their disciplines. Some of these (e.g. Susan Greenfield) have been appointed for just this purpose partly in order to maintain or win back public support for science at times when it has come under clouds of public disillusion. Ditto for history which can be the focus of public cultural debates. Unfortunately religion is not primarily an intellectual excercise and responds differently to public disillusion.

The problem you have found (so much interesting info “hidden away” from public discourse in the scholarly literature) is a strong argument, in my view, for major aspects of biblical studies to be taken over by secular history, archaeology and literature faculties in universities.

George, Arthur (30 August 2015) [NOW FORMATTED]. “Are “Dying and Rising Gods” Dead?”. Mythology Matters.

George, Arthur (30 August 2015) [NOW FORMATTED]. “Are “Dying and Rising Gods” Dead?”. Mythology Matters.