“in times of crisis, individuals regress to a state of delegated omnipotence and demand a leader (who will rescue them, take care of them)”

and that

“individuals susceptible to (the hypnotic attraction of) charismatic leadership have themselves fragmented or weak ego structures.”

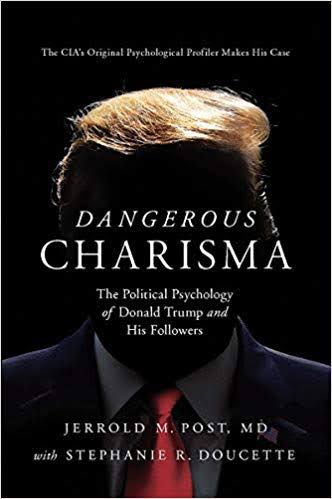

Jerrold Post believes the above hypotheses find support in clinical studies of persons who join charismatic religious groups, those with narcissistic personality disorders, and “psychodynamic observations of group phenomena”. Post and Doucette in Dangerous Charisma

describe the consequences of the wounded self on adult personality development and emphasize how narcissistically wounded individuals are attracted to charismatic leader-follower relationships, both as leaders and as followers.

As I read Dangerous Charisma I was regularly reminded of the time I joined a religious cult years ago and the stories that were regularly shared among members of “how God called us into his church”: certainly most, if not all, of the personal narratives involved tales of some kind of crisis each of us experienced and how “God rescued us” through leading us to encounter his “end-time Apostle”. After I left the cult I attended several other churches for a time and found the same sorts of experiences being “witnessed” even among less extreme fundamentalists or evangelical type Christians. Another perception that hit me, disturbingly, after having left the cult was seeing many of the same vulnerabilities, errors in thinking and willingness to rationalize the irrational and unprovable in society generally. Indeed, Post and Doucette make the point that the model they describe can work for good as well as evil: in times of crisis many turned to the charismatic Churchill, but that after the crisis was over the need for that sort of leader also passed and he was voted out. Other positive instances of such relationships involved Martin Luther King Jr and Mahatma Gandhi. But we all know there are weeds in the garden as well as fruit.

Two types of personality are described:

The mirror-hungry personality

This is the cult leader, whether religious (Herbert W. Armstrong) or political (Donald J. Trump)

The first personality pattern resulting from “the injured self” is the mirror-hungry personality. These individuals, whose basic psychological constellation is the grandiose self, hunger for confirming and admiring responses to counteract their inner sense of worthlessness and lack of self-esteem. To nourish their famished self, they are compelled to display themselves in order to evoke the attention of others. No matter how positive the response, they cannot be satisfied, but continue seeking new audiences from whom to elicit the attention and recognition they crave.

The ideal-hungry personality

This is the follower who is nourished by the above leader and who in turn nourishes that same leader:

The second personality type resulting from “the wounded self” is the ideal-hungry personality. These individuals can experience themselves as worthwhile only so long as they can relate to individuals whom they can admire for their prestige, power, beauty, intelligence, or moral stature. They forever search for such idealized figures. Again, the inner void cannot be filled. Inevitably, the ideal-hungry individual finds that their god is merely human, that their hero has feet of clay. Disappointed by discovery of defects in their previously idealized object, they cast him aside and searches for a new hero, to whom they attach themself in the hope that they will not be disappointed again.

The wounded self can arise from social, economic, personality crises. Job and economic and health insecurities, fears of one’s neighbours and newcomers and of conspiracies of powerful forces in government.

Post and Doucette emphasize that this model does not tell the whole story of Trump or political movements arising from the dynamics of the two types feeding off each other, but it does offer some insight into “charismatic leader-follower relationships.”

The charismatic leader as the mirror-hungry personality

The mirror-hungry leader requires a continuing flow of admiration from his audience in order to nourish his famished self. Central to his ability to elicit that admiration is his ability to convey a sense of grandeur, omnipotence, and strength. These individuals who have had feelings of grandiose omnipotence awakened within them are particularly attractive to individuals seeking idealized sources of strength. They convey a sense of conviction and certainty to those who are consumed by doubt and uncertainty. This mask of certainty is no mere pose. In truth, so profound is the inner doubt that a wall of dogmatic certainty is necessary to ward it off. For them, preserving grandiose feelings of strength and omniscience does not allow acknowledgment of weakness and doubt.

The leaders love the adulation of the crowds and can often speak for hours basking in their admiration; and the crowds love to be there, feeding and feeding off them.

The Language of Splitting is the Rhetoric of Absolutism

Central to the rhetoric is the “us-them”, the “me-not me”, the “good versus evil”, “strength versus weakness”, you are “with us or against us”. There’s nothing new here:

Maximilien Robespierre: “There are but two kinds of men, the kind that is corrupt and the kind that is virtuous.”

Hitler dwelt on the themes of strength and weakness, purity and impurity, the chosen (Germans) and the not chosen (Jews). The world is divided and one must conquer the other or be conquered.

We see this mindset in leaders who are convinced, and whose followers are also convinced, they are called on a religious mission. Followers often see the power of God behind them and the entire world of Satan is their opposition. Continue reading “Dangerous Charisma, Cults and Trump”