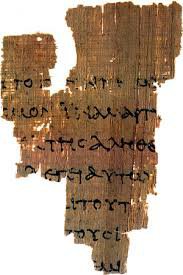

Patristic scholar Markus Vinzent has posted a few clear-headed pointers in relation to Dan Wallace’s apparent claims concerning the discovery of a piece of papyri containing some of the Gospel of Mark “reliably dated” — through paleography — to the first century.

Does confessional bias enter this scholarly debate? Markus thinks so:

While ideological disagreements, based on denominations, confessions, even religious backgrounds are mostly remnants of the past and rarely present in Patristic studies, we learn from this debate that whether one is evangelical or critical of evangelicals has even a bearing on the dating of papyri, something, the innocent scholar should think is a matter for impartial scholars to decide. And yet, because we are not dealing with bare evidence, but with witnesses of ‘canonical’ texts, ‘pure’ scholarship operates on a stage that is set by vested interests. How can one avoid to be located in any of the preset sceneries?

Markus includes a reminder about the same problem in relation to P52, the piece of manuscript containing words from the Gospel of John, that many “firmly date” to the first half of the second century

In his article on the misuse of papyrology in New Testament studies, B. Nongbri summarises what he calls ‘nothing surprising to papyrologists: palaeography is not the most effective method for dating texts, particularly those written in a literary hand … Any serious consideration of the window of possible dates for P52 must include dates in the later second and early third centuries. Thus, P52 cannot be used as evidence to silence other debates about the existence (or non-existence) of the Gospel of John in the first half of the second century. Only a papyrus containing an explicit date or one found in a clear archaeological stratigraphic context could do the work scholars want P52 to do.