Continuing from Ascension of Isaiah: Continuing Questions. . . .

. . .

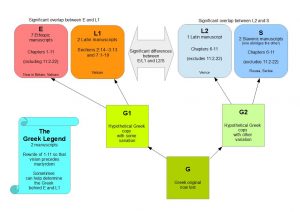

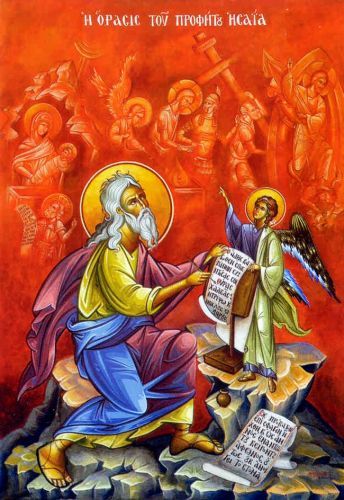

In points 6, 7 and 8 of section III of James Barlow’s Commentary on the Vision of Isaiah we enter into detailed discussions of how to assess the priority of different manuscript lines based on comparing particular differences of wording across the manuscripts. Barlow is challenging Charles’s conclusions: Charles argues that the manuscript line that leads to the Ethiopic text with the full pocket gospel is closer, overall, to the original Greek Asc. Isa. that is now lost; Barlow argues the reverse, that the manuscript line closer overall to the original Asc. Isa. is the one without the pocket gospel. The details are available in the linked article.

My thought on the entire debate may be considered dismissive or unfairly biased by some, but I suspect that no conclusion on the originality of the pocket gospel can be derived from the detailed discussions addressed by either Charles or Barlow. Charles at one point writes that it is “no doubt true in a few cases” that there are more original passages in the manuscript without the pocket gospel. That is, a lot of corruption in both manuscript lines has crept in since the original Greek Asc. Isa.

In other words, even if the shorter manuscripts without the pocket gospel contain a good number of passages that may be assessed as closer to the original Greek Asc. Isa. than the manuscripts containing the pocket gospel, it is not valid to conclude on that basis that the pocket gospel or much else in the manuscripts containing the pocket gospel is all a later development and that the pocket gospel is also a late interpolation.

Obviously there is room for disagreement with that viewpoint. In response to Charles’ words (p. xxii),

If SL2, in other words G2, represent faithfully the text as it stood in the archetype G, then it is clear that in such passages the fuller text of E or G1 is the work of the editor of G1. This is no doubt true in a few cases.

Barlow responds,

But if this logic is insurmountable, only wouldn’t it be true in ‘every’ case?

To which I would respond, No.

Longer or shorter?

On the other hand, some sections of the longer Ethiopic text look more original according to Charles. In the following text columns I have set out Charles says the longer text found in E is closer to what was in the original Asc. Isa. while the shorter L2/S manuscripts are abridgements of an original. Which column looks more original to you?

| E

10:25-28 |

L2/S

10:25-28 |

| 25. And again I saw when He descended into the second heaven, and again He gave the password there ; those who kept the gate proceeded to demand and the Lord to give. | 25 . . . into the second heaven, |

| 26. And I saw when He made Himself like unto the form of the angels in the second heaven, and they saw Him and they did not praise Him ; for His form was like unto their form. | 26. |

| 27. And again I saw when He descended into the first heaven, and there also He gave the password to those who kept the gate, and He made- Himself like unto the form of the angels who were on the left of that throne, and they neither praised nor lauded Him ; for His form was like unto their form. | 27. . . . into the first heaven, . . . and they neither praised nor lauded Him ; for His form was like unto their form. |

| 28. But as for me no one asked me on account of the angel who conducted me. | 28. |

| 29. And again He descended into the firmament where dwelleth the ruler of this world, and He gave the password to those on the left, and His form was like theirs, and they did not praise Him there ; but they were envying one another and fighting ; for here there is a power of evil and envying about trifles. | 29. And again He descended into the firmament . . . , and He gave the password . . . and His form was like theirs, and they did not praise Him there ; . . . |

. . . Continue reading “The Ascension of Isaiah: Another Set of Questions”