For earlier posts where I indicated the importance of some of Garbini’s approaches, see Testing (or not) Historical Sources for Reliability and Interview with Thomas L. Thompson #1.

The current post follows on from the previous one where we outlined the identification as “forerunners” of Israel the Banu Yamina (Benjamin) with their “davids” in the northern Syrian steppes during the second millennium BCE. One detail I did not note in that post but am adding here is that those same people had a particular group of diviners known as “nabi’um” — from which the Hebrew “navi”, meaning “prophet”, derives. So Garbini drew attention to the “Benjamin” confederacy having connections with Yahud, “davids” and “prophets”.

Giovanni Garbini traced the origins, migrations and settlements of Israel through his research as a professor of Semitic philology. In Garbini’s view, both “maximalists” (those who interpreted all archaeological evidence through the Bible) and “minimalists” (those who relied upon archaeological evidence ‘speaking for itself’) overlooked the evidence of epigraphy — the study of place and ethnic names in both the archaeological finds and the Bible. Garbini wrote that he…

found himself alone in supporting the thesis that adequate linguistic and philological preparation, with the support of extrabiblical sources, makes it possible to reconstruct the ancient history of Israel differently from the biblical account, using the Bible itself as the main source . . . (Scrivere, p. 11 – translation)

Throughout much of that second millennium in the northern Syrian steppes tribal groups were changing their seminomadic and pastoralist lifestyles when they built and settled into cities, allowing for new groups to move in to surrounding areas, with those semi-nomadic groups ever-changing their confederations, with new tribes emerging and older ones disappearing, always over the centuries in ethnic and tribal flux.

Egypt dominated the coastal and hinterland region as far as today’s Lebanon up until the 1300s BCE when we have Egyptian records informing us that new tribal groups and mercenary armies were threatening the security of cities over which Egypt had been the hegemon.

When Garbini integrates these Egyptian records with those of the Assyrian kingdom covering the ensuing century he pinpoints a critical new group of people who will become major players in the Levant: the name by which they were eventually most commonly known was the Aramaeans. They are sometimes named in association with one of the tribes of the Banu Yamini (or “Benjamin”, whom we met in the previous post.)

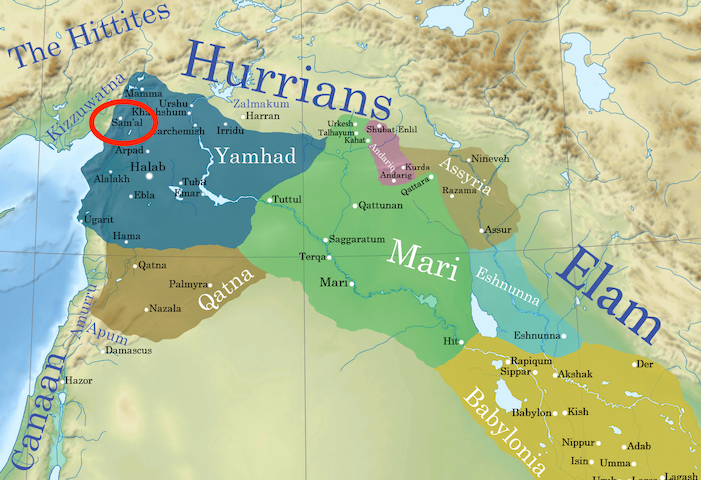

The Assyrians first encountered the Aramaeans in the northern region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

The region between the Tigris and Euphrates where the Assyrians first encountered these Aramaeans was known as Musri. Over the following centuries Musri was also identified on both sides of the Euphrates and in the ninth century, at the Battle of Qaqar on the Orontes River, some of the combatants were identified as Musri. Evidently they took their name from the region where they had originated. It appears that this branch of Aramaeans was gradually moving west.

1300’s BCE — Israel came out of ‘Egypt’, or Musri?

What are we to make of this name “Musri”?

Musri in the Bible

Musri is also mentioned in the Bible, or rather it was mentioned, because in the current text, both in Hebrew and Greek, this name has been systematically concealed through a series of textual interventions. (Scrivere, p. 22 – translation)

Garbini sets out the evidence that the Hebrew Bible we know today has several times replaced Musri with the name Egypt. When it was not replaced, it was spelled incorrectly to make it look like another name for Egypt (msrym instead of mwsr). At some stage scribes associated closely with Jerusalem and who were responsible for the Hebrew Bible attempted to downplay early links between Israel and the northern Aramaean people and region. They repeatedly stressed that though Abraham had come from Mesopotamia, Israel grew into a nation in Egypt and Yahweh who drew them out of Egypt. That was their identity.

But the evidence of philology, the names in the sources, indicate that Israel rather came from the north, from Musri and the Aramaic area, Garbini explains.

In Garbini’s view, some of the biblical books preserve very ancient traditions to this effect:

When you have entered the land the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance and have taken possession of it and settled in it, . . . Then go to the place the Lord your God will choose as a dwelling for his Name 3 and say to the priest in office at the time, “I declare today to the Lord your God that I have come to the land the Lord swore to our ancestors to give us.” . . . . 5 Then you shall declare before the Lord your God: “My father was a wandering Aramaean . . . — Deut. 26:1-5

Hosea fondly looks back on the time Israel was in Egypt and called out to be with God, but any perusal of that time in the Pentateuch quickly reminds us it was not a time of fond romance but one of tension, rebellion, so much so that God cursed the entire generation and even required Moses to die before entering the promised land. Hosea and Amos warn that Israel will be punished by being made to return to Assyria — and Egypt, in a context that suggests Egypt is near or under the dominion of Assyria. That makes more sense if the original text spoke of Musri, Garbini argues. There are other detailed arguments but I am avoiding the technicalities in this post.

The testimony of Hosea and the stories about the patriarchs, which were written at a later date, reveal the existence of a remarkably ancient tradition that traced the origins of Israel and Ephraim to the environment of the Aramaic-speaking seminomads who, starting from the 15th century BC, moved in the land of Musri, i.e. the vast steppe area of northern Syria that extended on both sides of the Upper Euphrates. Here, through processes that we do not know, a homogeneous group of tribes was formed, which took the name of Israel and at a certain moment began to move southwards. If several centuries later a prophet, who felt himself to be the custodian of the religious tradition of the group to which he belonged, launched reproaches and threats to his contemporaries who, in his opinion, did not honor the god who had brought them to the land of Canaan enough, it is very likely that the cult of that god played an important role in the formation of Israel. (Scrivere, p. 25 – translation)

Abraham, King of Damascus – and the Damascus Document

If, with Garbini, we leave aside the Bible and look at other traditions about Israel’s origins, we find that there was a tradition that Abraham was a king in Damascus: Continue reading “Israel’s Origins – before Palestine”