Later this year will see the third and final stage of an archaeological excavation on the site of an Iron Age temple only 7 kilometres outside Jerusalem. The site is Tel Moza, and the Temple was functional from the tenth to the sixth centuries BCE (that is, the 900s to the 500s). (After this coming session it is expected to extend digs in areas surrounding the temple.)

On the project website, telmoza.org, we read:

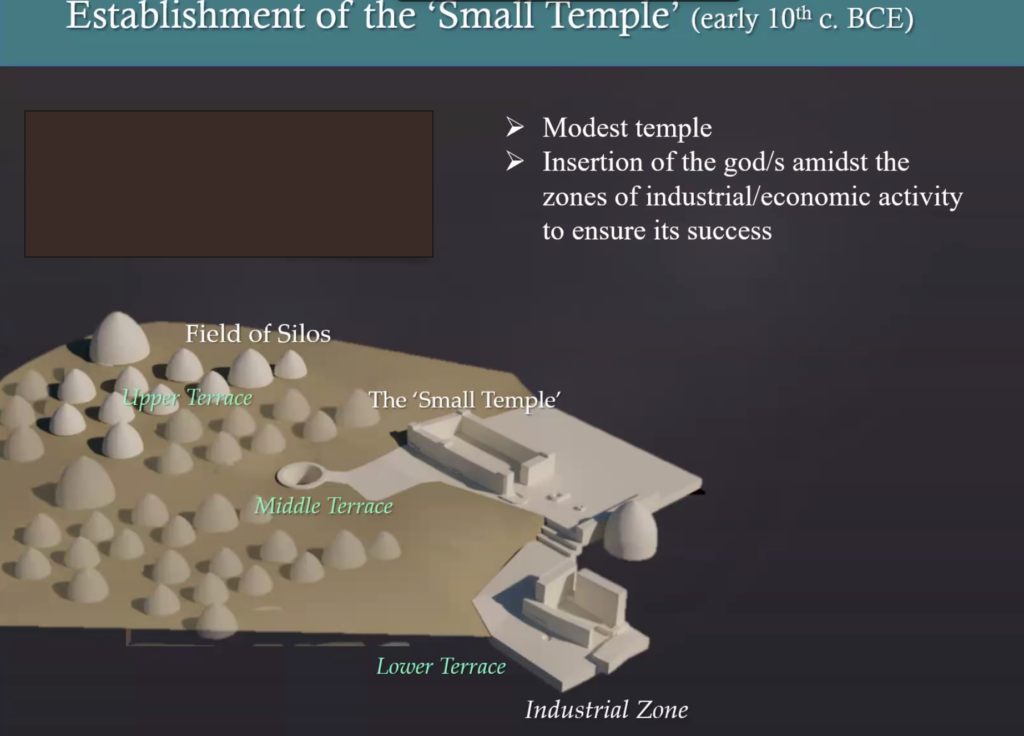

The finds indicate that Moẓa was settled continuously during the Iron Age II (10th to 6th centuries BCE) and the site was labaled [sic] “a royal granary specializing in grain storage, which supplied its products first and foremost to Jerusalem” (Greenhut and De Groot 2009: 223) due to the dozens of silos and two storage buildings found in it.

Here is a slide adapted from one shown by the archaeologist Oded Lipschits at this morning’s presentation at Southampton. It illustrates the silos in the region at the time the first small temple was constructed there. Silos were all capped by clay cones.

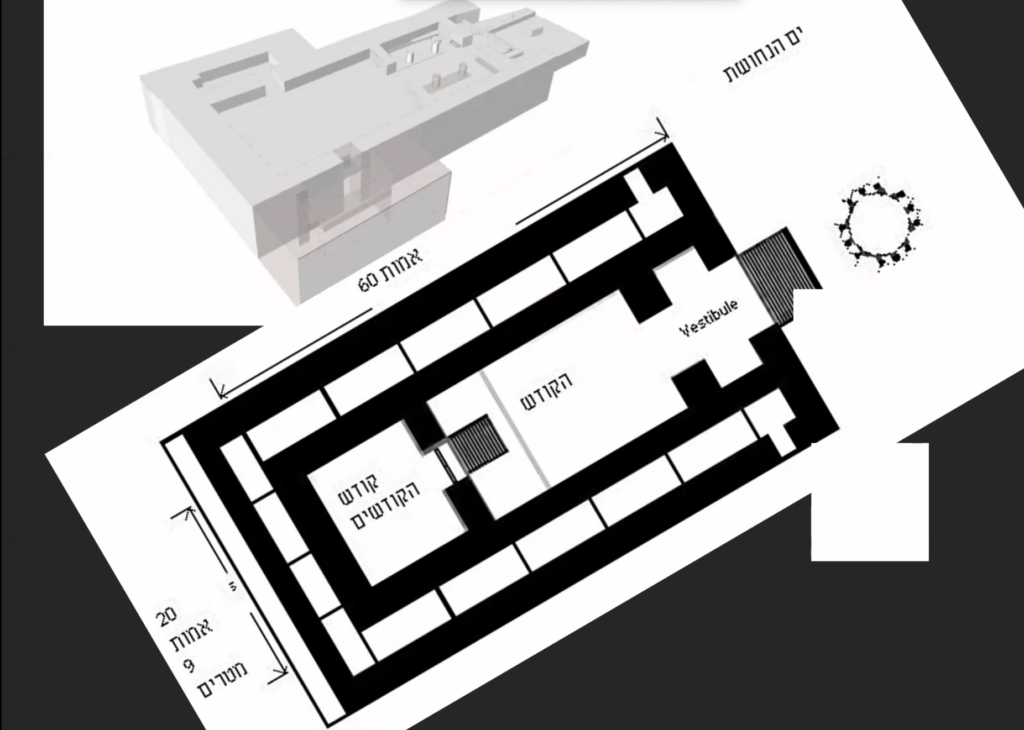

But in the early ninth century a large temple was built:

If that design looks familiar it is because it is the same structure as other temples of the time in Syria and Phoenicia and matches closely the biblical description of Solomon’s temple:

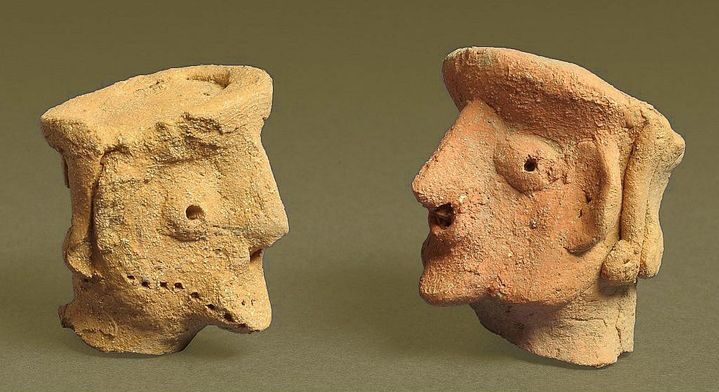

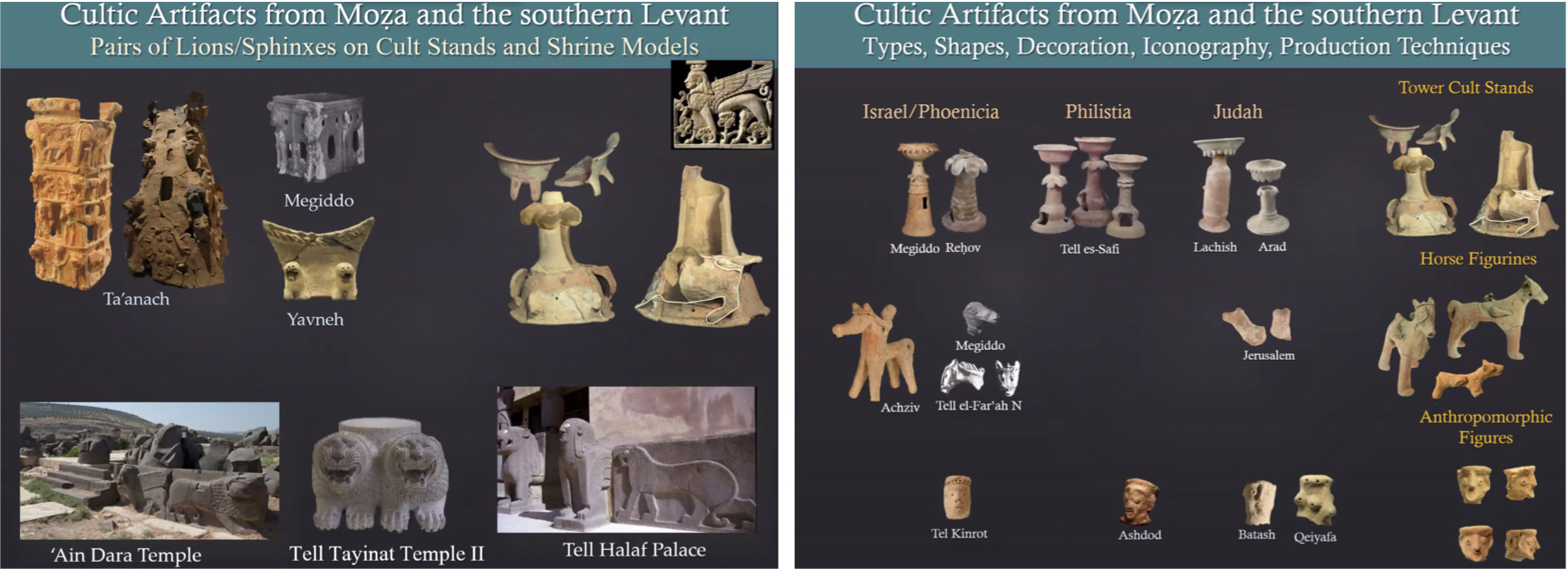

It was not a temple to Yahweh. Again from the telmoza.org site, some of the cult objects:

Lion statues were common in temples. The outline of a lion carving can be seen in the Moza artefact in the top right where it has been highlighted with a sketch outline (slides from Oded Lipschits’ presentation):

The evidence turned up so far on the temple site indicates that every thirty or so years there was a new extension or adjustment to the temple structure leading archaeologists to conclude that it was a well-established cult centre throughout those centuries. We don’t know if this temple should be seen as representative of other villages at the time. Did each community have its temple? The region around Tel Moza is thought to have supported about 250 families — the same size region as was around Jerusalem. Was the temple a site for daily visits or was it a site for annual pilgrimages? The answers to such questions are unknown.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Cool. Thanks for sharing.

Another fascinating post. Thanks Neil.

As I wrote in Gmirkin 2020: 82,

Important finds at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud included pictorial representations of the gods on pithoi and other scenes and decorative materials on plastered walls along with priestly writings of a religious character that mention Yahweh, Baal and El. The blessing inscriptions from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud constitute the oldest Hebrew dedicatory inscriptions discovered to date. The only place names mentioned were Teman and Samaria, which appear within the phrases “Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah” and “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah” (Meshel 2012: 3.1, 3.6, 3.9, 4.1.1). It is striking that there is no mention of a “Yahweh of Jerusalem.” However, the inscribed letters קר (thought to be an abbreviation for qorban or sacrifice) on a pithos made of Motza marl clay from the vicinity of Jerusalem indicates that offerings collected at Motza or Jerusalem were sent to supply the priests resident at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud (Meshel 2012: 67-68, 291-83). This suggests cultic activities that took place at Motza and Jerusalem’s temples were under Samarian control. A temple to Yahweh likely existed at Jerusalem in the ninth century BCE as a religious satellite of “Yahweh of Samaria” but was evidently neither significant nor well known in its own right.

Gmirkin, Russell, “‘Solomon’ (Shalmaneser III) and the Emergence of Judah as an Independent Kingdom.” Łukasz Niesiołowski-Spanò and Emanuel Pfoh (eds.), Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays in Honour of Thomas L. Thompson (Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies series; London: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2020), 76-90.

Meshel, Ze’ev, Kuntillet Ajrud (Horvat Teman): An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border (Jerusalem, Israel Exploration Society, 2012).

Also, I would not exclude the possibility that those cultic images are Iron II depictions of Yahweh, although I have not seen the presentation by Oded Lipschits yet. It would be interesting one way or the other, given the connection with Kuntillet ‘Ajrud (which was obviously polytheistic, but featured Yahweh).

Thanks for that reminder. One question I wish I had asked at the end of the session was whether we have anything more than assumptions that there was a temple in Jerusalem to Yahweh at that time. OL did bring up the many similarities between Baal and Yahweh in the discussion time, and added that Shalim is a god that is found in the names Jerusalem, Absalom, etc. Would we not expect to find a temple to Shalim there in Iron Age times?

(I have finally managed to get hold of a copy of Meshel’s volume on Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. I have much to catch up on in this area.)

At that point the Hebrews were hardly monotheistic, the big push for that beginning in the 6th century and taking several centuries to complete, no? I argue that as they became more and more monotheistic, the Temple in Jerusalem being the only valid temple was a power play by the Jerusalem temple elites. They went so far as to shut down/destroy temples in Elephantine, Egypt and Samaria. I wouldn’t be surprised if evidence is found that this temple was forcibly terminated.

On what evidence do you suggest that the “Jerusalem temple elites…went so far as to shut down… temples in Elephantine, Egypt”?

We have no knowledge whatsoever about when or how the Elephantine Temple was closed or destroyed or abandoned. Its remains were eventually buried under the neighbouring Khnum temple when it was enlarged, but we know nothing else. The involvement of Jerusalem temple elites is purely speculative.

The Samaritan temple of Mount Gerizim was indeed destroyed by the Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus in around 111 BCE, along with the city of Samaria itself in 107 BCE. Hyrcanus also conquered parts of Idumea. Taking advantage of the instability of the Seleucid Empire, he was a classic expansionist, militaristic Hellenistic monarch, so to ascribe the destruction to temple elites doesn’t particularly ring true.

According to Josephus, the Oniad Temple at Leontopolis in Egypt was razed by order of Vespasian in 73 C.E, after the Jerusalem temple had been destroyed, to ensure it didn’t become a rallying point for a new Judean uprising. By this date there was no Jerusalem temple and no elites controlling it or anywhere else.

“…whether we have anything more than assumptions that there was a temple in Jerusalem to Yahweh at that time. ”

In terms of archaeological evidence, none. The Temple Mount Sifting Project has found some Iron Age II-III artefacts derived from work done to the southern temple mount area (where the presumed temple is unlikely to have been situated) but as far as I know none are cultic in nature.

“…from work done to the southern temple mount area (where the presumed temple is unlikely to have been situated)”

The area of the post 19 BC extension project? The orientation of the walls surveyed and built then is intriguing: https://brill.com/downloadpdf/journals/aioo/77/1-2/article-p66_3.pdf?pdfJsInlineViewToken=2087594316&inlineView=true Page 21 of 31 especially. Someone then was into astrology obsessed with where and in what direction certain of the brightest stars rose in the night sky during the year.

The newly build steps leading down from the surface of the Haram to the El-Marwani Mosque in the so-called “Solomon’s Stables” are north of the Herodian extension. An elevation that locates it vis-a-vis the eastern wall development can be found on this webpage:

https://www.ritmeyer.com/2015/10/24/the-eastern-wall-of-the-temple-mount-in-jerusalem/

May I suggest You the reading of Garbini, Giovanni, “Scrivere la storia di Israele” (Paideia publ.), written in 2008 ? 😉

A wonderful suggestion and I have begun to do so. Thanks for the heads up. Unfortunately I cannot get a consistently clear copy online (the PDF file on Scribd has many areas that are too faint to read easily and less easy to copy and paste into a translator.) Nonetheless, I will persist with what I can read and invite you to make any corrections or additions to what I will surely post about the book. — But if you know of a better/clearer digital version do let me know.

😉 I’ve got my own paper copy…

I can’t suggest You :

https://www.libgen.rs/

search.php?req=

Garbini+Scrivere+la+storia+di+Israele&lg_topic=

libgen&open=0&view=simple&res=25&phrase=1&column=def

because it’s illegal in Italy, USA & Australia…

Yes, that turned out to be the same pdf file that I (also) found on Scribd. It’s the same pdf on several sites (despite different covers).