Okay, bad juvenile pun, I’m sure.

But I’m having trouble outlining Margaret Barker’s Israel’s Second God here. Firstly because work commitments have made it difficult for me to take the time to synthesize and then restructure the contents adequately, and secondly because Barker refers to many studies and theses that really require much unpacking for the uninitiated. (The following has taken weeks and weeks of broken bits of ten or twenty minutes to write, which makes for a very disjointed piece!) I’d find more enjoyment in taking time to explore some of those studies she refers to instead of her “grand thesis” that builds on them. I do have years-old notes from some of those studies filed away, and I would enjoy more digging those out and editing them to place here. But unfortunately I am currently working in “the most isolated city in the world” – Perth, Western Australia – over 4,000 k’s from my home and where my library is stored. I’d need my library to cross-check my old notes. And my next job and residence (only a few weeks from now) is to be even more distant from my library (Singapore!). Blogging here and on Metalogger will become a series of snatched ad hoc moments.

But to finish off chapter 2 of Margaret Barker’s Great Angel/Israel’s Second God . . . .

Continuing from Israel’s Second God, ch. 2 contd . . . .

It has widely been accepted among scholars that El was the most ancient name for God and that this name was later replaced by Yahweh. The patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob knew God as El, but from the time of Moses and the Exodus he was known as Yahweh.

Exodus 3:15

Yahweh, the God [El] of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob has sent me to you; this is my name for ever, and thus [as Yahweh] I am to be remembered throughout all generations.

Exodus 6:2-3

I am Yahweh. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac and to Jacob as El Shaddai, but by my name Yahweh I did not make myself known to them.

Names for god such as El Shaddai appear in “early stories” in Genesis and Exodus, and in ancient poetry such as found in the Balaam oracles in Numbers 24.

But Margaret Barker points to a problem with this idea:

The name of EL is used more often in texts from later periods, especially from the time of the Babylonian exile, such as in – – –

Second Isaiah

Job

Later Psalms

Daniel

Apocalyptic writings

Hellenistic Jewish literature

If it were the more ancient name that had been replaced by Yahweh, then why does it not eventually disappear? Why is it used more often at a later period in the texts listed above?

Explanations (or ad hoc rationalizations?) proposed hitherto to explain this “anomaly” include:

a cultural interest in reviving old liturgical forms

vicissitudes of fashion

influence of the Hellenistic Zeus Hypsistos

Barker suggests another explanation:

Maybe El never fell out of use at all.

Maybe there were many who resisted the attempted reforms of the Yahwists and Deuteronomists when they attempted to displace (or merge) El with Yahweh.

Maybe those who maintained their independence from the Deuteronomists continued to think of the god El and the god Yahweh as a separate deities all along, perhaps even as Father and Son gods

Some reasons to think this may have been the case:

1. The Old Testament contains polemics against a number of Canaanite deities, especially Baal, but no polemic at all against the head Canaanite deity, El. (Here Margaret Barker is drawing heavily on O. Eissfeldt’s article, “El and Yahweh”, published in the Journal of Semitic Studies (1956), pp.25-37.) Is this because El was never viewed as a threat to Yahweh? Baal and Yahweh were very similar deities. Both were storm gods. Both loved roaring around in clouds and making thunderous noises and terrorizing mortals with their flashes of lightning. And if both were sons of El (see previous post notes for details) one can understand the need for one to displace the other.

But Yahweh also takes on some of the characteristics of El in some passages. He takes on El’s role as king presiding over a heavenly court. Why was there no apparent conflict with El as there was between Yahweh and Baal?

2. The patriarchs in Genesis did things forbidden by the author of Deuteronomy — such as setting up local altars throughout Canaan and having their sacred trees or groves and pillars. But if Deuteronomy is a sixth century text or later, then such practices must have been practiced as late as that time. Otherwise the author would have had no need to condemn them.

Margaret Barker draws on studies that have argued that El worship was practiced throughout Canaan at local altars, and that various of these altars and pillars were given special significance as a part of the Genesis narratives about the travels and adventures of the patriarchs of Israel.

Just as the Canaanite barley festival came to be associated with the Exodus, and as the Canaanite wheat harvest was linked with the law being given at Sinai, and the grape harvest with the enthronement of the king, so also were the Canaanite customs of local altars and pillars given special meanings from narrative associations with the patriarchs.

Would this explain the El epithets associated with these altars and places of groves and pillars? (e.g. Bethel, Penuel)

This worship of El, at local altars, may indeed have continued right through in exilic times, despite efforts or hopes of the Deuteronomists to replace it with a centralized worship of Yahweh.

Other advocates of Yahweh (not necessarily hostile Deuteronomists) may have merged the stories referring to El into their accounts of Yahweh. El and Yahweh may have been merged by these authors without thoughts of tension or conflict existing between the two, as was the case with Yahweh and Baal.

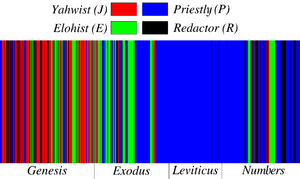

J and E (the documentary hypothesis) are hypothetical, not facts

John Van Seters (Abraham in History and Tradition; In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History) has pioneered significant challenges to the documentary hypothesis that proposes that much of the Old Testament was composed by combining two “national epics” labelled by scholars as J and E. And as Margaret Barker stresses, J and E are only hypotheses. They are not “facts”. Repetition and ongoing references to J and E have led to them becoming “facts” in the minds of many, but they are still hypotheses.

Comparing the Pentateuch with the Histories by Herodotus

Van Seters and other scholars have compared the Pentateuch with the work of Greek historian, Herodotus. Its author, who was a Yahwist, was collecting and compiling materials in a way similar to the way Herodotus worked to compose his Histories. Both use a

“mixture of myths, legends and genealogies to demonstrate the origin of Athenian society, its customs and institutions”

The Greek historian, not unlike the author or compiler of the Pentateuch, used several sources:

“some were written, some were tales he heard on his travels, and sometimes he used ‘to fabricate stories and anecdotes using little or no traditional material, only popular motifs or themes from other literary works.”

Both wrote with the same purpose: to give their audiences “a sense of identity and national pride”. This would have been particularly necessary for Jews who had been dispossessed by the exile.

If this is how the Pentateuch was compiled, then we cannot expect to find in it evidence for anything but the concerns of the exiles, and one of these seems to have been to relate the El practices to those of Yahweh’s cult. (p.22)

The mutating transmission of oral traditions

Barker refers to R. N. Whybray (The Making of the Pentateuch) to dismiss the old idea that oral traditions of Israel’s history were handed down rigidly without change throughout generations before being written down. Tellers of tales were more likely to adapt stories to the needs of their audiences.Thus the history in the Pentateuch more likely reflects the needs and interests of the later audience for whom it was written than any accurate ancient history of Israel. If so, then the references to El in the Pentateuch were not archaic relics from yesteryear, but were part of the religious interest and life of audiences as late as the sixth century b.c.e.

Scissors and paste or a single Mastermind?

The Pentateuch very likely represents but one religious point of view in ancient Israel. And this is perhaps easier to grasp if we concur with modern studies that argue that the Pentateuch’s complex patterns are evidence for a literary artistry that must have come from the creative mind of a single author. The old idea that the Pentateuch is a higgledy piggledy clumsy pasting of various traditions and sources together no longer stands scrutiny.

And if the Pentateuch does represent but one author’s viewpoint, and that of his sect or group, then what other viewpoints existed beside it? The prophets have long been recognized as religious innovators, and it is quite possible that the author of the Pentateuch was another.

The gods El, Baal and Yahweh merge

The Canaanite deity El was an “ancient of days” father god, creator/procreator of heaven and earth, merciful, presiding over the heavenly council of lesser divinities.

The Canaanite Baal was a god of storm and thunder. He appeared in clouds with terrifying displays of lightning and thunder. He was a king and judge. But he was also subordinate to (and a son of) El.

The Bible portrays deadly conflicts between Baal and Yahweh. Witness Elijah’s slaying of the prophets of Baal. But there is no similar conflict between Yahweh and the Canaanite god El. Yet there was no similar tension with El.

Barker’s explanation is that the religion of Israel long acknowledged two gods, El and (like Baal, his son) Yahweh. The biblical storm and cloud imagery attached to Yawheh (from Exodus to Ezekiel) marked Yahweh as an alternative to Baal. But biblical literature also refers to El throughout the history of Israelite literature, and not just in the earliest periods. El is used throughout the late Second Isaiah, for example. Barker believes that this points to Israelite religion in many quarters acknowledging both El and Yahweh as distinct deities.

The Deuteronomist (and Yahwist) did attempt to fuse El and Yahweh, but their re-writings and beliefs did not change the thinking and writings of all. Some authors, particularly those of Jewish texts that did not become part of the later orthodox Jewish canon, continued to think of El and Yahweh as separate deities, even as father and son deities, just as El and Baal had been in Canaanite mythology.

The biblical Yahweh appears to have taken on the attributes of both El and Baal.

If, as the evidence testifies, the early name for the god of Israel was El, one question to ask is when Yahweh replaced (or took on the attributes of) El. And at what point were the earlier stories of Israel overwritten so that El was replaced with Yahweh? The prevailing documentary hypothesis (J and E) has indicated that this fusion occurred early in the kingdom of Israel. But this is not a fact, as Barker is at pains to point out, but only one of several hypotheses. The fusion may well have been as late as the exilic period.

But more significantly, Margaret Barker argues that these questions are not just about the different names.

Compare Psalms and Ugaritic poems

Psalms, for example, that address both El and Yahweh have traditionally been interpreted as using two names for the one god:

Psalm 18:13

Yahweh thundered in the heavens, and Elyon uttered his voice

But compare a Canaanite religious poem from Ugarit:

Lift up your hands to heaven;

Sacrifice to Bull, your father El.

Minister to Ba’l with your sacrifice,

The son of Dagan with your provision.

Does the Canaanite poem inform us how we should be reading the Psalm — not seeing the different names as poetic synonyms for the one person, but in fact different names for different deities?

Compare the image of Matthew’s parable of sheep and goats

Matthew 25:31-46 depicts the king sitting in judgment, but the king also acknowledges a higher authority than himself — his Father.

Compare Baal, who also was a king who sat in judgment, yet was himself subordinate to his father, El.

Barker asks us to question the survival of an ancient Canaanite image of gods appearing in a Christian text. She proposes that it makes sense to think of those ancient images in fact being maintained throughout Israel’s history, and this despite the impression we easily pick up by assuming that the Pentateuch and re-written biblical texts are representative of ancient Israel’s religion. These texts should, rather, be seen within the context of nonbiblical literature as well, and we should also consider more critically the implications of the biblical texts having been edited by later Yahwists or Deuteronomists.

Compare Daniel and the Son of Man imagery

The same parable in Matthew 25 also refers to the King as the Son of Man.

And the Son of Man kingly image is clearly pulled from Daniel 7.

J. A. Emerton (The Origin of the Son of Man Imagery, JTS New Series ix (1958), pp 225-42) cited by Barker discusses this more fully. Too fully to summarize here. Daniel 7:13-14, he notes, speaks of the Son of Man “coming in clouds” and “like” or “in appearance as” a son of man. The same latter description coheres with the description of Yahweh in Ezekiel 1:27. Yahweh is also regularly associated with appearing and traveling in the clouds.

If the Son of Man, then, is Yahweh, who is The Ancient of Days?

In my vision at night I looked, and there before me was one like a son of man, coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into his presence. He was given authority, glory and sovereign power; all peoples, nations and men of every language worshiped him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and his kingdom is one that will never be destroyed.

How to explain the presence in this passage in Daniel of TWO divine figures?

How could Daniel, a second century text, and one that was written in a context of pagan efforts (Antiochus of the Seleucid Empire) to subdue that form of Jewish religion that opposed all efforts to impose certain pagan uniformities (banning circumcision, sacrificing unclean animals on the temple altar) toy with the supposedly pagan imagery of El (the ‘ancient of days’ and high god in Canaanite mythology) and Baal (the son of El and one given kingly authority and who rode in clouds)?

Is the simplest explanation that Yahweh replaced Baal among Israelites, but that for many he long continued to maintain his subordinate and clearly separate identity from the high god El? And this situation — one school following the Deuteronomist view that identified El and Yahweh, another that maintained their separate identities — continued through the first century c.e.?

Does Christianity represent one branch of ancient Israelite religion, the branch that maintained the distinction between El and Yahweh, while rabbinism represents another, that which was advanced by the Deuteronomist and Yahwist scribes?

Like this:

Like Loading...