Continuing my reading of part 2 of Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier . . . .

Continuing my reading of part 2 of Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier . . . .

. . . o . . .

At the heart of Nanine Charbonnel’s thesis lies the question of how much we read in the gospels was written in a figurative sense and how much literal. Arthur Schopenhauer famously declared that all religious truth is expressed allegorically or mythically. But then the question becomes how such a beast can be controlled and not leave us pondering all sorts of fancies. And what devils arise if we know we are reading allegory and conclude that it is therefore not true! To bypass such anarchy Charbonnel determines to explore the precise mechanisms that have gone into the production of the gospels.

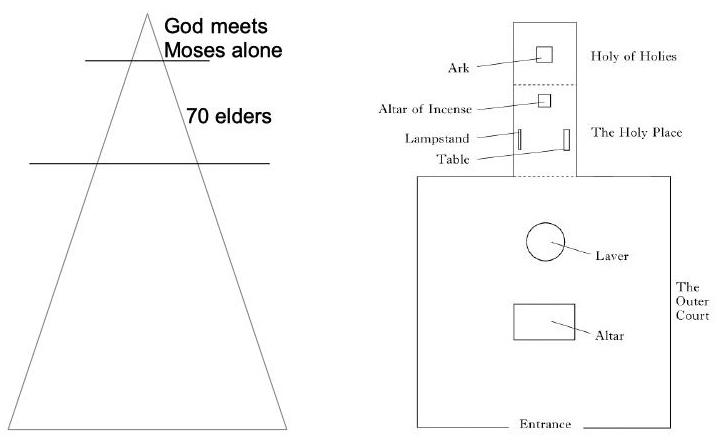

We have referred earlier to the nineteenth critical author David Friedrich Strauss. Strauss declared many episodes in the gospels to be myths but what he meant by that was a narrative constructed around an Old Testament precedent. Strauss recognized the OT origins of the infant Jesus having to flee tyrants (Pharaoh and Moses), the star of Bethlehem (the star of Balaam’s prophecy), the magi visiting Jesus (the magi of Isaiah and gifts of Psalm 72), Jesus’ multiplications of the loaves (the manna in the desert and Elisha’s 20 loaves), the water into wine (Moses converting the brackish water into pure), the transfiguration of Jesus (Moses and Elijah with YHWH on the mountain), and so forth.

Where Strauss most notably failed was in his belief that Judaism does not allow for any notion of a suffering Messiah. He failed, therefore, to see that the most central event of the gospels was likewise a “mythical” adaptation of the OT. The significance of this viewpoint is that Strauss recognized that the author of the Jesus story was not starting from a “historical event” but from a theme, an idea. He wrote, for example, how the idea of a literal Messianic “son of God” grew out of texts like Psalm 2:7 (“Thou are my son, this day have I begotten thee”) and the prophecy in Isaiah for a child to be born to a “virgin” (Life of Jesus Critically Examined, I. ch.3, §29).

A Different Type of Symbolic Writing

Central to Charbonnel’s thesis is an understanding of different types of symbolic writing. Ernest Renan captures the most common view of the gospels as being quite unlike any form of allegory or symbolism:

That our Gospel is dogmatic I recognise, but it is by no means allegorical. The really allegorical writings of the first centuries, the Apocalypse, the Pastor of Hermas, the Pista Sophia, possess quite a different charm. (Renan, Life of Jesus, Appendix)

For Charbonnel the symbolism of the gospels is also striking even though quite unlike that of texts we typically think of as symbolic. Rabbinic writings contain another form of figurative tales that are typically called midrashic. But for Charbonnel there is another type of midrashic literature not found in those later Jewish texts.

Look at the Shepherd of Hermas, for example. Much of the text is clearly symbolic with characters personifying the church, virtues, etc. However, at other times it relates scenes that could well pass as realistic story even though we know they should be interpreted allegorically. Charbonnel raises the suggestion that our canonical gospels and the canonical Book of Revelation might be two sides, an obverse and reverse, of a symbolic form of narrative.

Similarly with the Dead Sea Scrolls. Many are written as pseudepigraphs, in the names of the patriarchs, or of the prophets. They appear to be a new type of literature at variance from what we are familiar with in the Old Testament collection. The scrolls indicate the presence of a particular community and a leader, the Teacher of Righteousness. Many assume both of these to be a literal group and a historical leader. Yet we have no way of proving either thought. As the “community” in the scrolls in fact an ideal community, a “new Israel”? (Charbonnel does not make the specific connection with Philip Davies but the same possibility can be seen underlying some of his discussion of the meaning of “Israel” — see What do we mean by Israel?) Are we reading a literary creation of a visionary utopia rather than a historical account of an actual group of persons?

Midrash

So far I have used the term “midrashic”. Charbonnel speaks of “midrash”. We have come across considerable controversy in some quarters of the meaning of this term so let’s settle what we mean, exactly, in this series, or in Nanine Charbonnel’s text. Charbonnel draws upon the definition set forth by the Jewish scholar Daniel Boyarin. I quote from the relevant section of The Jewish Gospels:

Although a whole library could [and has been) written on midrash, for the present purposes it will be sufficient to define it as a mode of biblical reading that brings disparate passages and verses together in the elaboration of new narratives. It is something like the old game of anagrams in which the players look at words or texts and seek to form new words and texts out of the letters that are there. The rabbis who produced the midrashic way of reading considered the Bible one enormous signifying system, any part of which could be taken as commenting on or supplementing any other part. They were thus able to make new stories out of fragments of older ones [from the Bible itself), via a kind of anagrams writ large; the new stories, which build closely on the biblical narratives but expand and modify them as well, were considered the equals of the biblical stories themselves. (Boyarin, p. 76)

Such a definition is broad. The later rabbinic midrash can be made to fit a narrower definition. In this discussion, however, we are looking at a form of Jewish literature that preceded those rabbinic texts.

So in this context what can be said about the Gospels? Continue reading “A Midrashic Hypothesis for the Gospels”