Is it possible that the Bible’s account of priests and prophets contains hints of borrowing from the Greek world? Not that those Hellenistic features mean we have to jettison entirely sources and influences closer to the Levant. Let’s look at another section of Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible (2016).

|

Previous posts:

|

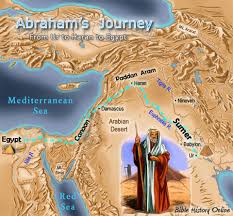

The narratives of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) are set in Syria, Sinai, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Jordan, Phoenicia, Canaan and that fact affects the way we imagine how the authors created those tales. We picture them drawing upon memories, traditions, stories both oral and written from the those same lands. We expect scholars to look to the law codes, the religious practices, the governing institutions and social customs of the Levant, the Hittites and Mesopotamia for the context of the biblical literature and, as expected, they do indeed find points of contact in those places.

Meanwhile we barely catch glimpses of the Mediterranean world in those scriptures: firstly, there are passing references to Noah’s descendants through Japheth being assigned to settle the Hellas (Greece); secondly, a mysterious dream of an apocalyptic future is revealed to Daniel. Yet Anselm Hagedorn suggests on the basis of Joel and Zechariah that the contact with the Greek world may have been “more intense than the Biblical sources want us to believe.” (2004. p. 60)

Joel 3:6

You sold the people of Judah and Jerusalem to the Greeks, that you might send them far from their homeland.

Zechariah 9:13

I will bend Judah as I bend my bow and fill it with Ephraim. I will rouse your sons, Zion, against your sons, Greece, and make you like a warrior’s sword.

They may not be well known outside academia but there are significant studies that do place the Levant (including “biblical Israel”) within the orbit of the East Mediterranean’s geographical and cultural littoral, most conspicuously from the time of Alexander’s conquests but also culturally centuries earlier. Some of these studies (ones that I have been able to access in preparation for this post) are:

It is in this context that Gmirkin’s thesis focuses on a Hellenistic provenance of the Pentateuch. In particular he looks to the centrality of the Great Library of Alexandria established in the wake of the Greco-Macedonian conquests ca 300 BCE and assigned the responsibility of collecting copies of all the literary works of the known world. It was through this central repository that Judean scholars surely had access to the great philosophical and political works of Plato, Aristotle, and others. It is also pertinent to Gmirkin’s thesis that one widely popular topic among literate circles throughout the Greek speaking world was the question of “the best form of government”. And that’s exactly the sort of literature that the Pentateuch is — a narrative history and detailed exposition of “perfect laws”, an “ideal constitution”, the wisest of law-books among all nations, as Deuteronomy 4: 5-8 informs us:

Behold, I have taught you statutes and judgments . . . for this is your wisdom and your understanding in the sight of the nations who shall hear all these statutes, and say, ‘Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.’ For what nation is there so great, who hath God so nigh unto them as the Lordour God is in all things that we call upon Him for? And what nation is there so great, that hath statutes and judgments so righteous as all this law which I set before you this day?

So for Gmirkin’s thesis it is not without significance that the earliest secure evidence of the Pentateuchal writings dates to that time, the third century BCE, and that the primary theme and interest of these writings is the same as we find among Greek philosophers of that time — the establishment and exposition of ideal constitutions and perfect laws intended to support the happiest and most righteous society imaginable.

Among some striking synchronicities between the worlds of Greece and the Hebrew Bible identified by Gmirkin and discussed so far have been:

- the 12 tribe organisation of the people

and

- the subjection of the king to moral guardians or priestly supervision

In the final post in this section of Gmirkin’s study we look at some aspects of the Pentateuch’s Aaronid priests, related Levites and roles of prophets. We will see that while the Pentateuch has significant departures from Athenian practice and Plato’s philosophical ideals there remain certain points of contact that are worthy of attention.

-o-

Temple Priests

We know from Aristotle (Politics 1300a, 19ff; Athenian Constitution 57) that Athenian priestly offices were appointed either by popular election or by lot, but that it was necessary for a certain ratio of candidates to belong to two ancient priestly families, the Eumolpidae and Kerykes. One of course thinks of the Aaronids in the Pentateuch and the Zadokites in the Book of Ezekiel.

Plato contemplated an ideal constitution (or rather a second-best constitution, since anything human had to be inferior to divine systems) and decided it was most necessary for priestly functions to be filled by persons not only pure physically, but also morally and according to family heritage:

we shall test, first, as to whether he is sound and true-born, and secondly, as to whether he comes from houses that are as pure as possible, being himself clean from murder and all such offences against religion, and of parents that have lived by the same rule. (Laws 759c)

In following up Russell Gmirkin’s endnotes I came across a notice that the title of “high priest” was unattested for any Greek city up to the middle of the third century, or the Hellenistic era.

After this time it becomes very common. . . . Plato’s … Laws anticipates the future and may have been an important influence upon Athenian practices in Hellenistic times. (Morrow p. 418)

It is interesting that Plato’s philosophical discussion should be considered as a possible source for institutional innovations in Athens in the Hellenistic era. That classicists take this view strengthens Russell Gmirkin’s argument that the same writing influenced the authors of the Pentateuch.

What is particularly interesting, however, is that Plato further spoke of a need for the priests of Apollo and Helios to be of the most virtuous character. Physical perfection was not sufficient. Continue reading “Bible’s Priests and Prophets – With Touches of Greek”

Like this:

Like Loading...

I should follow up my previous post with a clarification of Weinfeld’s argument as he presented it in his 1993 book, The Promise of the Land. The bolding is mine for the benefit of those who don’t want to read lots of text but just hit the highlights.

I should follow up my previous post with a clarification of Weinfeld’s argument as he presented it in his 1993 book, The Promise of the Land. The bolding is mine for the benefit of those who don’t want to read lots of text but just hit the highlights.