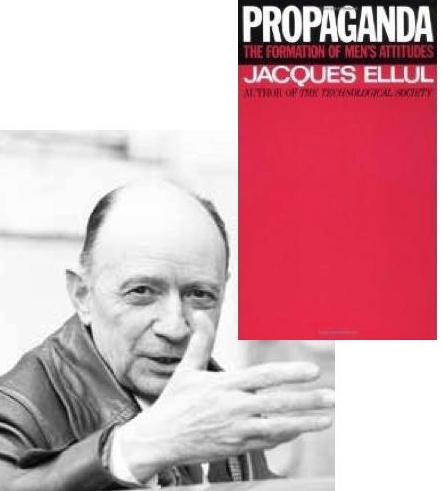

Frequently when I post something on topical subjects (e.g. “understanding Hamas”) someone will comment that my views are grounded in ignorance and supply a link to a webpage, often a mainstream news media article, to enlighten me of the facts.

When I see a news media article I will read it but I will also be conscious that it is but a single report that cannot possibly tell the “whole story”. We know the proverbial many witnesses of a car accident.

But let’s break that down a little.

Firstly, the news media report is usually the work of a journalist who needs to collect information. How often are they an eyewitness of the event? And even if they are an eyewitness, is that enough to report “the whole story”. (Again the proverbial soldier in the trenches reporting on a battle of which he necessarily witnessed only a part.) Who does the reporter interview for the information? And recall that the questions one asks and how they are framed can determine the types of answers one gets.

We know that very often reporters will rely upon official statements. Official statements themselves are generally the claims of certain politically interested parties. So again, how can we be sure we are reading “the whole story”?

And the media organization itself needs to generate revenue. They need to produce a product (news) that will in turn be sure to generate that revenue, so it is necessary for them to best study how to present the news, as well as to make decisions about what news should be prioritized. News has to sell to a particular market for the media organization to survive.

And that will always necessarily mean much detail needs to be stripped from the story, if background informative details were ever collected in the first place.

People who work for the organization are no doubt on the whole very sincere and believe wholeheartedly that they are doing a public service. That’s good, too, for the organization because it doesn’t want to struggle with any sort of cognitive dissonance.

So I keep in touch with “what’s happening” through mainstream media but at the same time I understand how filtered what I am reading necessarily is. It can never tell me the whole story.

For the whole story I always need to do a little bit of digging behind the media reports. That usually means finding reputable research into the actors of various news events. I mean scholarly and/or investigative journalist research. And I can never rely on just one piece of research. I always need to follow up the sources of certain works (via following through the sources mentioned in endnotes) and comparing with other research by other scholars, perhaps with a different perspective or background.

Or at least it means searching out news reports from diverse and often contrary political and other points of view. Such diversity won’t give final answers, in most cases, but it will generally make one aware of questions that need to be asked of each report and where further information is required.

And what I invariably learn is that one comes to have a very different perspective and understanding of what one reads in the news media when one comes to know a little of the persons, the organizations, the history of what is being reported.

Just to reduce this to a micro and personal example:

Some years back there was a newspaper and tv news report of a man who had shot another, killed him. In the news media he was a murderer, a villain in a dramatic story that caught the public’s attention. It just so happened that I knew that man personally for some years and considered him a friend. I spoke to him while he was waiting for his trial and later visited him a few times in prison. I knew a side of him that never made it to the media, or if it did, it was always in a distorted fashion. I am thinking of the many times his wife had betrayed him, his daughters turned against him, and I could only say I would have absolutely no idea what I would have done had I been in the same situation as he had been. But through the media the story was always black and white, or at most just a few hints of grey but never enough to lead anyone to question the core of the narrative.

Stories of events in the mainstream media are never comprehensive and can never, by definition, provide a genuine understanding of what has happened, why, or seriously inform us about the persons involved.

Like this:

Like Loading...