All posts in this series are archived at Henaut: Oral Tradition and the Gospels

(This post extends well beyond Henaut, however.)

.

I have recently posted insights by John Drury and Michael Goulder into the literary character of the parables in the gospels. (The vocabulary and themes are part and parcel of the larger canvass and thematic structure of each gospel.) Drury has further shown that they are not, as widely assumed, to be based on everyday commonplace events but are in fact bizarre and unnatural scenarios. (Sowers did not scatter seed so wastefully as per the parable of the sower, for example.)

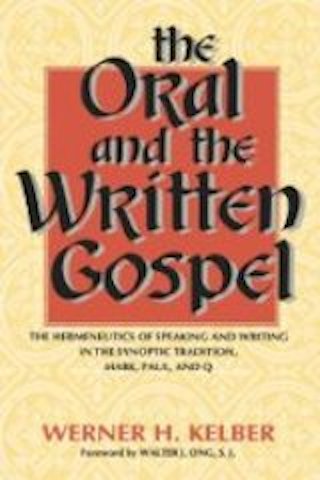

Shortly before Drury’s book was published (1985) a work by Werner Kelber appeared, Oral and Written Gospel (1983). I recall devouring Kelber’s books, pencil-marking them, thinking about them, applying them to other works I read, when I first began to study study what scholarship had to say about Gospel origins. His Oral and Written Gospel remains one of the most underlined and scribbled-in books on my shelf. Back then Kelber led me to ask so many questions of other works I was reading; now I find myself asking more critical questions of Kelber himself.

Shortly before Drury’s book was published (1985) a work by Werner Kelber appeared, Oral and Written Gospel (1983). I recall devouring Kelber’s books, pencil-marking them, thinking about them, applying them to other works I read, when I first began to study study what scholarship had to say about Gospel origins. His Oral and Written Gospel remains one of the most underlined and scribbled-in books on my shelf. Back then Kelber led me to ask so many questions of other works I was reading; now I find myself asking more critical questions of Kelber himself.

Arguments for the parables originating in oral performance

Here is what he wrote about the significance of the parables as evidence for oral tradition lying behind the sayings of Jesus in the gospels.

The oral propriety of parabolic stories requires little argument. “A parable is an urgent endeavour on the part of the speaker towards the listener.” [citing Carlston] Speaking is the ordinary mode of parabolic discourse, and writing in parables seems almost out of place. (p. 57, my own bolding and formatting in all quotations)

There are three distinctive features about parables that Kelber identifies as clear signs that they originated as oral performances. Continue reading “Doubting an Oral Tradition behind the Gospels: The Parables”