Continuing with my discussion of Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier . . . .

Continuing with my discussion of Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier . . . .

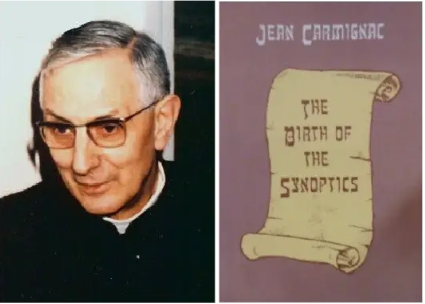

An earlier post in this series, Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. Chap 3b. Creative Intertextuality, briefly touched on the ways stories in the Pentateuch came to be rewritten so that one mirrored another: e.g. Abraham and Sarah’s experience in Egypt and being expelled under duress pairs with the subsequent Exodus narrative. Deuteronomy itself is a rewriting of the earlier books of the Pentateuch. We read stories as “fulfillments” of other stories; scenario types are written as a kind of commentary on other stories, or as indicative of a deeper meaning of other stories. We see narrative “typology” within the works of the Hebrew Bible so when we find the New Testament narratives similarly drawing events and persons of the Jewish Scriptures we must understand that we are witnessing a continuation of a literary practice that was centuries old. And just as Deuteronomy was a certain kind of rewriting of the previous books so the Acts of the Apostles may have a similar function with respect to the preceding canonical gospels.

But Charbonnel goes further yet. The Incarnation itself was a literary product of the way the Hebrew language conceptualizes temporality.

When reading this section of Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier I was reminded of my first lecture in French 101 at university. “If there is one lesson I want you to take away from this course, it is to understand that other people think differently” — those were the first words of the professor in that classroom and I can hear his voice still. The same lesson certainly applies to biblical Hebrew and time.

The general idea being argued is that stories (a kind of midrash) were written as if taking place in the past yet in the minds of the original storytellers and audiences they were “outside time”, “ever-present” — both future and also past but always present. (Compare the brief discussion of Hebrew “tenses” in the previous post.)

In the OT Prophetic writings the expression for “in those days” was essentially a pointer to messianic time and not a literal historical (or specific future historical time) marker. When the second chapter of the Gospel of Luke begins “in those days” it is a signal that we are reading of the messianic time spoken of in the prophets. It is not, despite our natural English translation reading and context, primarily pointing to the historical time of Augustus and Herod. To help us see what is going on here, compare the Protoevangium of James. We read there an elaboration of the nativity scenes in Matthew and Luke. The elaboration of those canonical stories fills in gaps and ties up loose ends that are left with us from the bare canonical accounts. Those “fillers” are taken from other narratives in the Jewish Scriptures, especially 1 Samuel. We read about the birth of Mary in circumstances that recall the births of Samuel and Isaac. Then we read of the childhood of Mary and her giving birth to Jesus in scenes that involve midwives and Salome and a new setting, a cave. We are reading a retelling of the canonical narratives with ideas from both the Scriptures and other interpretations presumably discussed among the author’s contemporaries. The new story is not historical. It is an interpretation constructed from attempts to answer questions about the canonical stories by weaving in new ideas from Scriptures and elsewhere. The story is about “the coming of Christ”.

I am reminded of the argument of Thomas L. Thompson about the way the stories of the Hebrew Bible were written. He is discussing what we classify as the “historical” books of the Bible.

I am reminded of the argument of Thomas L. Thompson about the way the stories of the Hebrew Bible were written. He is discussing what we classify as the “historical” books of the Bible.

When we ask whether the events of biblical narrative have actually happened, we raise a question that can hardly be satisfactorily answered. The question itself guarantees that the Bible will be misunderstood. One of the central contrasts that divide the understanding of the past that we find implied in biblical texts from a modern understanding of history lies in the way we think about reality.

. . .

Chronology in this kind of history is not used as a measure of change. It links events and persons, makes associations, establishes continuity. It expresses an unbroken chain from the past to the present. This is not a linear as much as it is a coherent sense of time. It functions so as to identify and legitimize what is otherwise ephemeral and transient. Time marks a reiteration of reality through its many forms. Nor is ancient chronology based on a sense of circular time, in the sense of a return to an original reality. The first instance of an event is there only to mark the pattern of reiteration. It is irrelevant whether a given event is earlier or later than another. Both exist as mirrored expressions of a transcendent reality. Closely linked with this ancient perception of time is the philosophical idea we find captured in the Book of Ecclesiastes (1: 9-11):

There is nothing new under the sun. If we can say of anything: that it is new, it has been seen already long since. This event of the past is not remembered. Nor will the future events, which will happen again be remembered by those who follow us.

When God created the world, he created the heavens and the earth and everything in them. All of history is already included in the creation. This is also what lies behind the idea of ‘fate’, which, as a classic premiss of Greek tragedy, reflects the human struggle against destiny. The only appropriate response is acceptance and understanding.