Seeking, but not finding

I think I have been searching in the wrong places for the origin of the Jesus figure in our New Testament writings. Of course it would be easiest to assume that there is some truth to the gospel narratives and that there was a historical preacher by that name who was crucified and whose followers believed he rose from the dead and went to heaven. But then I would be unable to explain why the earliest uncontested and independent evidence we have for that person does not appear until a full hundred years after his time and without a hint about how that life, so rich in allusions to mythical acts and persons, came to be known. Or I could conjure up an explanation that involved ordinary (generally illiterate) persons passing on ever more imaginative “oral reports” about the person but that would be letting my imagination fly in the face of studies that tell us that’s not how fabulous tales about historical persons originate. (They are composed from the creative imaginations of the literati.)

I used to fuss fruitlessly over trying to understand what might have led to the first gospel, widely believed to have been the Gospel of Mark. I liked the idea that that gospel portrayed a Jesus who could readily be interpreted as a personification of an ideal Israel, one who died with his nation in the catastrophe of 70 CE (the destruction of the Jewish Temple by Titus along with myriads of crucifixions of Jewish victims) and rose again to establish a new “spiritual” Israel in the “church”. But that idea did not explain the kinds of Christianities (there were many types) that swelled and plopped like bubbles in a vast Mediterranean hot mud spring. Not even if we moved the gospel to a later time so that it had the Bar Kochba war (132-135 CE) in mind.

An old door reopened

Nina Livesey (re)opened a door to a room for me that maybe I should have investigated more thoroughly before. In the book I recently discussed, Livesey speaks of a multiplicity of “Christian” schools comparable with the many philosophical schools in Rome. They usually centred around a prominent teacher, attracted an inner circle of disciples while also holding open public sessions, and would not be averse to publishing both trial and final versions of tracts illustrating some point of their teachings. Livesey revives the idea that the letters attributed to an apostle named Paul were published by one such school, one led by Marcion. Marcion was also reputed to have produced “a gospel”, one that many in later antiquity and since have considered to be an early form of our Gospel of Luke.

Let’s pause there and collect our thoughts for a moment.

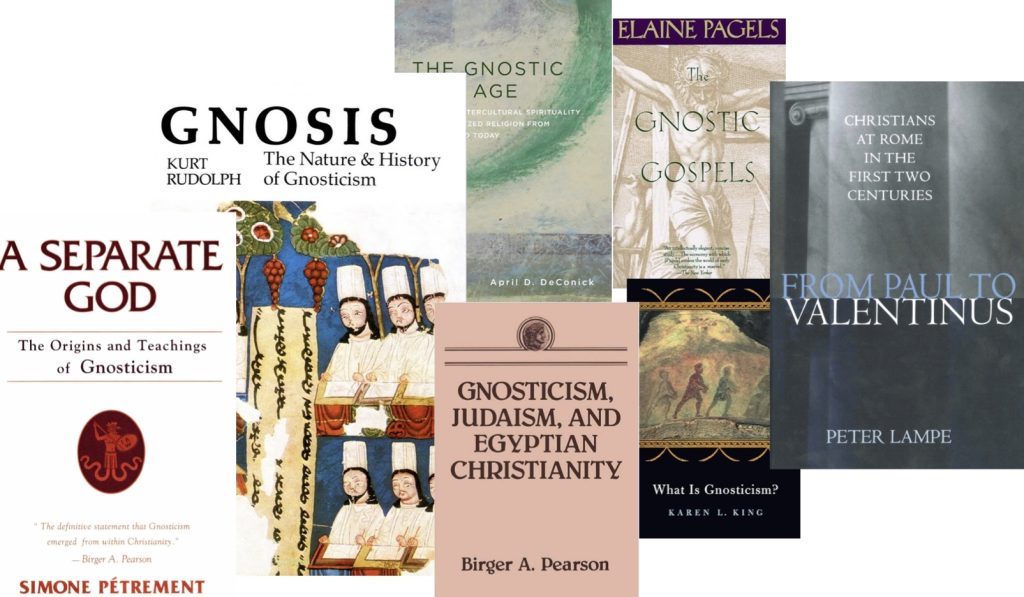

Marcion was not the only “Christian” teacher in Rome around the middle of the second century. Other teachers or school heads (not all in Rome) around the same period include Apelles, Basilides, Cerdo, Heracleon, Justin, Marcion, Saturninus/Satornilos, Tatian, Valentinus . . . You get the idea. There were many competing teachings. Some of them came to be dismissed as a consequence of being labelled as “gnostic”. But they were there from the beginning — at least if by “the beginning” we insist on appealing only to independently verifiable sources.

Now when Marcion published “Paul’s letters” some other schools picked them up and used them as foils through which to teach their own doctrines. Multiple interpretations and textual variants were the result. That’s how the schools worked: they would be open to engaging with each others’ teachings, either with modifications, elaborations, or outright rejections. So it is difficult from our perspective to always know what the original teachings of some of these schools were: they were capable of changing over time.

Back to the gospels. When Marcion wrote up a life of Jesus, he was using that figure of Jesus as a means of promoting his (Marcion’s) view that “Christianity” was an antithesis of the Jewish religion. Marcion’s Jesus was not even real flesh and blood but a spirit being in the appearance of flesh and blood: the antithesis even in this respect to the physical ordinances of Moses.

Schools opposing the biblical narrative

But other schools had other ideas about Jesus. More than that, they had ideas about the origins of the Jewish religion and even of humanity itself that we today would find quite bizarre. There were multiple ideas about god and creation. Many of these ideas were borrowed from Greek philosophy, some from Greek literature and myths, as well as from the Jewish Scriptures. Some said that the god who created this world was a god lower than, and ignorant of, the ultimate “Good God”; some said the serpent in the Garden of Eden was actually a benefactor of humankind and the god who punished him (according to the Book of Genesis) was the wicked god; some said that the line of Cain (depicted in Genesis as the first murderer) was the righteous genealogy; some said Jesus first appeared in the form of Adam’s third son, Seth. Indeed, Jesus held different positions among these various schools. He might be seen as one of a number of spirit beings who were “born” in the earliest moments of time. Or he was a human, fathered by Joseph, who was possessed by a spirit being called Christ. Some saw him as hating the laws of the god of Moses and promising deliverance to all whom the Jewish god had condemned.

But other schools had other ideas about Jesus. More than that, they had ideas about the origins of the Jewish religion and even of humanity itself that we today would find quite bizarre. There were multiple ideas about god and creation. Many of these ideas were borrowed from Greek philosophy, some from Greek literature and myths, as well as from the Jewish Scriptures. Some said that the god who created this world was a god lower than, and ignorant of, the ultimate “Good God”; some said the serpent in the Garden of Eden was actually a benefactor of humankind and the god who punished him (according to the Book of Genesis) was the wicked god; some said that the line of Cain (depicted in Genesis as the first murderer) was the righteous genealogy; some said Jesus first appeared in the form of Adam’s third son, Seth. Indeed, Jesus held different positions among these various schools. He might be seen as one of a number of spirit beings who were “born” in the earliest moments of time. Or he was a human, fathered by Joseph, who was possessed by a spirit being called Christ. Some saw him as hating the laws of the god of Moses and promising deliverance to all whom the Jewish god had condemned.

I suspect it is impossible to ever find a way to reconcile all of these teachings. They span events from time before creation right through to the present and beyond. One thing they all seem to have in common, though: they are all opposed to the orthodox understanding we have of the Jewish Scriptures, or the Old Testament. Not all of them, as far as we are aware, include a place for Jesus. But of those that do, Jesus has a role that is opposed to the Mosaic Law and traditional Jewish Temple. (Not unreasonably, given that Jesus is derived from the name Joshua who was originally understood as the successor to Moses.)

In other words, what I am imagining here is a situation that we can with reasonable assurance place as early as the opening decades and middle of the second century — a time when a find a multiplicity of schools with various notions proposing narratives that contradicted those we read in Genesis and those of the “orthodox” interpretation of the Jewish bible more generally.

Where did those ideas come from?

An Anti-Jewish/Judean time

I am tempted to begin with the beginning of the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) as proposed by Niels Peter Lemche and in some depth by Russell Gmirkin. This takes us back to the beginning of the Hellenistic era (from the time of Alexander the Great’s conquests) when Samaritans and Judeans, with the aid of Greek writings, collaborated to construct a narrative of origins that we read today in the books from Genesis to Deuteronomy or Joshua. Genesis in particular has retained hints that its authors were trying to incorporate multiple gods whom later readers would equate with Yahweh. Most scholars have seen multiple hands and schools of thought going into the final product of the Pentateuch. It is not difficult to imagine some intellects associated with the production of the first bible continuing to raise alternative ideas that were infused with Greek philosophy and myth or to imagine that some of this kind of divergent thinking continued through to the Roman era. What are surely critical turning points, however, are the calamities that befell the Jews (or Judeans) first under Vespasian and Titus (the first Jewish war of 66-70 CE), the uprisings and widespread massacres of Jews a few decades later under Trajan and then the “final solution” by 135 CE under Hadrian when the Jews were forbidden even to set foot in Jerusalem.

The bloody times coincided with the emergence of “Christian schools” in Rome. Let’s take a step beyond Nina Livesey’s specific focus on the letters of Paul appearing at this time. Let’s suggest that it is these times that witness the emergence of schools teaching the “end” of the Jewish laws. These times further witness teachings declaring the falsehood of the narrative of creation by the Jewish god, or at least teaching that this creation was evil or less than “good”. Imagine that this is the time when we see the namesake of Moses’ successor, Joshua/Jesus, promising deliverance from the judgment of that lesser god of the Jews.

If we can imagine all of that, we are, I think, confining ourselves to what the evidence in our second century sources allows.

But how does any of that explain the Christianity we recognize today?

It doesn’t. If that’s all we had, no doubt those negative teachings of Marcion, of Valentinus and others would have fallen by the wayside in time.

From antipathy to antithesis to … fulfilment

But something happened after Marcion released his story of Jesus, a Jesus who was an “antithesis” of the best that the god of the Jews could offer.

Another school, perhaps one associated with the “church father” Justin, or with Basilides in Alexandria (I don’t know and can only surmise), responded with an opposing narrative about a Jesus who was less an “antithesis” of the Jewish god than a “fulfilment” of all that the Jewish god had hoped for but had failed to achieve hitherto.

If that happened, we have a revolutionary moment. We no longer have a negative response to “the Jewish religion and scriptures”; rather, we have a way of capturing and finding new and enriched meaning in that old religion and its hoary sacred writings.

What if Jesus could be transformed from an anti-Moses or anti-Yahweh figure into a ‘higher than Moses’ figure, a fulfilment of the higher ethics of god who was henceforth to appear as a newly discovered deity, or as the old deity whose true character was only being seen clearly now for the first time — or as the “one sent to reveal” that newly understood deity?

Such a Jesus had the power to enrich and so preserve with new meaning texts that had long been revered (even among non-Jews). Allegorical reading could infuse them with new meanings. The old was discarded, yes, but it was also retained and revivified as throwing the “new” into 3D relief by its shadows: Joseph and Moses and David and Elijah (and so on) of the Old Testament prefigured the Jesus of the New — at least if read with a little imagination. A gospel could depict Jesus as a personification of an ideal Israel, healing others but suffering unjustly only to be raised up and bring all humanity to salvation. Another gospel could present Jesus as a new Moses delivering a “higher law” in the Sermon on the Mount. And so on.

I suggest that once one or some of those schools (probably in Rome but not necessarily confined to there) discovered a way to both reject and embrace with new meaning the old Mosaic order of things, they were on a winner, as we might say today.

Such a Jesus, just like the other original Jewish writings and again like the writings of “proto-Christian” (including “gnostic”) schools, drew upon the inspiration of Greek myths and philosophy to flesh out their teachings. The Jesus with us today drew upon one additional source — the Jewish Scriptures — and found as a result a longer-lasting heritage. Various “schools” may have competed for the most outstanding way to oppose and supplant the religion of the Jews who from 70 to 135 CE were suffering the calamities of Vespasian, Titus, Trajan and Hadrian. The form of Christianity that became a religion that could boast of a “higher fulfilment” and stronger appeal to literati and hoi polloi alike was the one that learned how to infuse venerable texts and the experiences of their advocates with new meaning and build on their foundation. Rejection of the Old, in way, yes, like the teachings of other schools … but with one important twist.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

YAHWISM vs JUDAISM and Jesus: recent scholarship by Gad Barnea (Yawhism in the Archaeminid empire) and Yonnatan Adler (both archeologists) suggests that Yahwism was a worship of Yahweh that spanned across the Mediterranean, Persia, Egypt up to the British isles! This was different from Judaism which was a product of the Hasmonean Empire; The Septuagint, composed primarily representing the latter (for purposes of the Alexandrian Library) was also used for worship of Yahweh, but also included a diverse array of scripture that originated from all across the Mediterranean. Dr Margeret Barker in her “The Great Angel” has done a great job of identifying Yahweh the first born son/Angel/ high priest/logos (like Philo describes) of El the Transcendental God: and that the first Christians eg Mark, Luke, Mathew & John conceptualise Jesus as Yahweh incarnated eg Mark 1:3 refers to “prepare the way for the LORD (Yahweh)”; or “before Abraham was I am” in John 4:58 or Paul in 1Cor10:1-4 as the Cloud& spiritual rock that followed the Israelites in the desert.

Margeret Barker also identifies Yaweh as “descending through the heavens” in the Ascension of Isaiah (date of origin 80CE -120 CE) which may have been pictured Yaweh being killed prior to the Gospels (proper) being written in the 2nd century. Why was Ascension of Isaiah written? It is unclear- perhaps Yahweh was identified through synchretism as a dying and rising Messiah? Or maybe in response to the destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 70CE.

But Mark could have been euhemerizing Yahweh as Jesus and then triggered the cascade of the Gospels? Marcion and Mark could have been in the same school (Heresis)?

I have discussed the works of Barnea, Adler and Barker on this blog — do a search on their names in the “Search” box near the top of the right margin on this page. Cult sites for “Yhwh” have been found throughout Syria and down to the areas around Edom, but I don’t think any of them extend the cult throughout the Mediterranean or to the British Isles. Barker poses some interesting interpretations but care needs to be taken to sift interpretation and argument from clear “fact”. It is quite possible that the Ascension of Isaiah is a late work. Again, we have debates but little certainty.

The model I have in mind places Mark as a response to a gospel that was associated with Marcion. But Mark was not the first appearance of a Jesus as a fulfilment teaching.

Barnea refers to the Elephantine evidence with regards to the presence of Yahwism (have heard him refer to British Isles in an interview); I agree with your take on MBarker. But philo’s description of Logos as son of God/ arch angel/ high priest of Gods heavenly temple indicate he most likely aligned with platonsitic ideas and Deuteronomy 32:8. The references in Mark& the Gospels, Paul’s letters and Jude etc indicate they were perceived Jesus as Yahweh incarnated

“Now I desire to remind you, though you are fully informed, once and for all, that Jesus, who saved a people out of the land of Egypt, afterward destroyed those who did not believe.”

Jude 1:5 NRSVUE

https://bible.com/bible/3523/jud.1.5.NRSVUE

It also has explanatory power for where Jesus (Yahweh Ho Shua- Yahweh the Saviour) comes from- otherwise he does not have any reasonable OT presence. Regards

Love your work

I meant to add Elephantine evidence signifies Yahwism in Egypt

It is possible then, Jesus was invented from whole cloth?

Not as a deliberate synthetic fiction and/or a conspiracy, but as normative human sociological/religious impulses which includes religious syncretism, mimesis, intertextuality.

I think it is worth taking a closer look at the other forms of Christianity that we can identify in the same time period as the gospels — on the assumption that they are all second century. I doubt many would think that the Jesus in the “non-orthodox” Christianities owed anything to a historical figure.

A remarkable thing about Jesus is how unremarkable he is when read as a mythological being. He’s a demigod with one divine parent (who is the chief sky god), he performs miracles, is betrayed, dies, and then ascends to heaven. There’s a reason the early Church struggled to shake off Hercules worship for centuries – it’s hard to say “THIS guy is fake but THIS guy who seems very similar is totally legit!”

As a figure we would have no problem thinking that he’s as made up from whole cloth as Zeus or Wayland – we would laugh at the idea that he was real if we come to it cold IMO. And the philosophy put in his mouth is interesting but again not exceptional for the period. The linkage with the OT is the oddest part but then linking your teachings to “ancient wisdom” was as good a selling point then as it is for “New Agers” today. Romans loved “ancient wisdom”, so that’s very much a bums-on-seats tactic and it’s hard to argue that it didn’t work.

The search for the original Jesus is, I’ve come to realise, a waste of time. The interesting historical quest is for the original Christians.

Which depends on how one defines “Christians”. Perhaps a good case can be made for a definition that makes the early (“proto”) orthodox responsible for the NT literature that presented Christ as the fulfilment (as distinct from an antithesis or antipathy to the OT. But Marcionites and Valentinians were considered Christians also in antiquity. So I don’t think there can be a clear dividing line. It’s like asking when life began, or when homo sapiens appeared. Origins of anything can become a very murky question. (With this post I’m suggesting that the anti-Jewish schools that we associate with gnositicism mutated into Christianity.)

It’s natural selection at work. You start with a lot of ideas of things that look like what we think of today as Christians and the ones which survive in the environment of the day replicate themselves into the future, gradually changing to survive in changing intellectual environments (or trying to stop that change).

The idea of “fulfilment” being the magic gene which suddenly catapults one family or genus of Christians ahead of the rest is very interesting as it does seem to explain somethings which have bothered me for years after I realised just how deep the pagan Greek roots of the character Jesus went (Oedipus’s empty tomb was the first big shake for me). How did something SO Greek in form and thought get grafted onto Jewish religion? I knew that Romans were real magpies for Ancient Wisdom™ but I never felt that was enough to sustain more than a fad.

The fulfilment idea really feels like it opens a door for pre-existing Jewish believers who were disenchanted by real-world events to move forward without classing *themselves* as complete apostates, giving the new religion a real grass-roots foundation that yet-another-saviour-demigod doesn’t seem like it would have. Of course, old-school Jews would not have seen it that way and we instantly have antagonism and feelings of betrayal springing up.

It all sounds very plausable.

Fulfilment further enhances the appeal of Jewish Scriptures among pagans, too. That appears to have been the hook that snagged Justin.

Given my recent discussions of the nature of history (and the place of Bayes in it) I have to balk at seeing “natural laws” at work in human affairs, however. 😉

Well, all you need is variance between copies (which you particularly get in the oral phase of a new sect) and some scoring function for the resulting alternatives, which here is simply how many people your idea appeals to. This is the actual original meaning of the word “meme” as Dawkins coined it – a cultural equivalent of the biological gene. The enforcement of Orthodox texts is a particular bulwark against mutations which we see very strictly applied in both Judaism and Islam.

Ultimately, the religions we see around us today are the ones that survived and reproduced via people taking them up and spreading them. That is very much an evolutionary process and I don’t think anyone would seriously suggest that ideas do not compete or that the cultural environment does not affect which ideas are acceptable to the population.

Do you really think Dawkins’ memes “behave” like genes? Is there not some circularity in the explanation when memes are said to have success for the same reason as genes? Evolution produces predictable vestigial organs; nothing like that with memes — whose success is all so neatly explained in hindsight (hence the circularity?)

OP: “There were many competing teachings. Some of them came to be dismissed as a consequence of being labelled as “gnostic”. But they were there from the beginning — at least if by “the beginning” we insist on appealing only to independently verifiable sources.”

“[47:10] The Gnostics [i.e. Chrestians NOT proto-orthodox Christians] were dying in that amphitheater as bravely as members of his own congregation . . . Irenaeus believed that true Christianity, was his Christianity [pseudo-orthodox Christianity]—he thought that the Gnostics were holy anarchists. He wanted to show the world an organized and universal Church, not a secret sect. [47:51]” –TESTAMENT with John Romer. Part 4 – Gospel Truth?”. YouTube @ https://youtu.be/dFPPGgYzhH0?t=2836

The gospel of Marcion priority puts into the spotlight Lord Chrest…

“No text in the entire world ever says Christ – although plenty of them say Chrest.” –Martijn Linssen

“Gospels, Epistles, Old Testament: the order of books according to Jesus Chri st” Amazon Kindle Edition @ https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CKFD5J98

I don’t make as big a deal about the “Chrest”-“Christ” divide that some do. It was a common enough pun that made no difference to the underlying theological ideas. I have been meaning to post about it — drawing in particular on a work by John Moles.

The Book of Revelation offers us a very Jewish Jesus. He’s a savior, a Messiah of Davidic descent, a warrior. The name “Jesus” (or Joshua) means a savior, and in that sense is like the term “Christ.” The latter term identifies the particular savior. Saviors are rampant in Greco-Roman times, looks like. John of Patmos addresses 7 churches. He’s familiar with 7 Christian churches, but not with Paul or Paul’s letters, and not with a gospel. That alone is enough to make me question the traditional dating of both letters and gospels. It also suggests the Jewish nature of (First Century?) Christianity. Well, we knew it was originally a Jewish sect. Along come Cerdo and Marcion, and now you have an Antithesis and the letters of Paul as the proposed basis of the sect. Let’s sweep away the Jewish demi-urge (Yahweh) entirely! Then you get reaction: Justin, Irenaeus. Justin focuses heavily on Jewish scripture, distorting it from its more obvious meanings every chance he gets, in favor of the fulfillment of prophecy idea. The Jews never understood what they were about, apparently! We’re going to explain it to them! But to do it we must suppress these heretical Antitheses. What are we talking about? Jesus Christ, of course. And what is our focus? Is it on who his family was? Is it on his childhood and upbringing? His education? His physical appearance? His political loyalties? His personal mannerisms?No, it’s on what kind of god he is. Jewish? Anti-Jewish? Greek? Meek & mild? Warlike? His mother was a goddess, by the way, one of those virgin mothers of the ancient world. Father was God. This process appears to me to describe a literary creation of the 2d C. arising originally out of a Messianic sect of an oppressed people in the First.

Yes, the Jesus in Revelation is indeed one who is at odds with the Jesus promoted by “those who teach permission to eat meat sacrificed to idols” etc. And if Thomas Witulski is right, then the Jesus of Revelation is even hoping for a Bar Kochba victory over Hadrian’s legions. Paul-Louis Couchoud pitted the Jesus of Paul and the Jesus of John as figures in conflict. Is not the Jesus of Revelation a prophesied conquering Messiah rather than a “fulfilment that replaces” kind of idea, though?

You speak of an oppressed people. Along with them, I wonder, are the gentiles who converted and others who sympathized. They were the ones caught squarely in the middle of two worlds and needed to justify their place to both. Marcion himself may have been a Jew or at least a proselyte (he knew a lot about the Scriptures) and proposed antithesis as the way forward. But whether antithesis or fulfilment, a major feature was the message to the non-Jews.

But yes indeed, the Jesus of Revelation is very much like a part 2 of the “Son of Man” in Daniel.

John of Patmos=Jewish Jesus

Marcion=Non-Jewish Jesus

Justin=Post-Jewish Jesus

Gospel John= Anti-Jewish Jesus?

I missed this added comment of yours when I edited my first reply. Yep —

John of Patmos = “Jewish Jesus” = Daniel “Son of Man” in the spirit of apocalyptic conqueror.

The Gospel of Mark then inverts Daniel’s Son of Man, as we know.

Wonderful envisioning. If founded in reality, proof positive that Jesus was a narrative being constructed, or rather cobbled, from imaginary bits.

I think it explains a lot — including why the search for “an original Jesus” always been obliged to rely upon assumptions hanging in mid air.

I share your desire for a model of Christian origins that explains the diversity that seems to have existed almost immediately. The solutions to me are either an earlier starting point, perhaps with figures such as the Teacher of righteousness or others, which allow more time to have for these developments, or what I like to call a ‘soft start’.

The keystone concept IMO is the ubiquitous ‘second power theology’ shared in some form by diverse Hellenized Judaism, so-called Gnostics and the proto-orthodoxy. The idea that God Most High had ‘sons’, aka agents/angels/holy spirit that were emanations of the deity. Some of whom proved unable or unfit for the roles they were assigned. Without spending too much time on that, suffice to say, the schools as diverse as the Valentinian, Philonic, and Justinian have as a foundational tenet the concept of emanations of God. Given the ethereal/philosophical nature of this concept, we are unlikely to discover a single point of origin for them all in common. Rather than a diffusion of sects, it seems simpler to assume a fusion. This is what I mean by a ‘soft start’, no single event but the interplay of existing sects and concepts, eventuating after centuries into a dominant orthodoxy.

As to the idea of an historical Jesus, the Philonic Alexandrian school had suggested ancient figures such as Melchizedek or Aaron were in reality the Logos in humanlike form. It’s not difficult to believe the same was believed of a later person in some of the tributary sects while others retained a purely ‘spiritual’ concept. That seems to have been an issue very early.

This is the second time posting this. If I have not done something right, please advise.

New posters (and sometimes older ones for some reason) have their comments sit in limbo until I or Tim check them first. It’s an unfortunate necessary step.

Yes, there were the “endless genealogies” of some of the gnostics and I see those as attempts to replace a cosmic history – the one implied in the Jewish Scriptures – with a more philosophical system. But my point is that they were all aimed at replacing or denying the Jewish Scriptures and fundamental Jewish religious ideas (the Temple, Creator God and Lawgiver, the Patriarchs). Then one day some teachers found a way to both “replace” and “honour with higher meaning”. That was the winning ticket.

Something I found that goes against the thesis that Marcion believed that Yahweh was the evil creator god is these verses (1Cor 10): “For I do not want you to be ignorant of the fact, brothers and sisters, that our ancestors were all under the cloud and that they all passed through the sea. 2 They were all baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea. 3 They all ate the same spiritual food 4 and drank the same spiritual drink; for they drank from the spiritual rock that accompanied them, and that rock was Christ. Nevertheless, God was not pleased with most of them; their bodies were scattered in the wilderness.

These verses indicate “Paul” did think Christ was Yahweh the Saviour (similar to 1 Jude 5 “Though you already know all this, I want to remind you that the Lord at one time delivered his people out of Egypt, but later destroyed those who did not believe”

In my view its is possible that Marcion had Jewish background, saw or conceived Jesus as Yahweh (like the earliest Gospel writers) but believed in a Demiurge/an Angel that controlled the age/world (God of this world/rulers of the world/age) who had given the Torah/law to Judeans eg Gal 3:19-“Why, then, was the law given at all? It was added because of transgressions until the Seed to whom the promise referred had come. The law was given through angels and entrusted to a mediator”. This led to the production of his Gospel and his pauline collection.

That the Torah was ordained by Angels was apparently a known concept: See Josephus-

“And for us, we have learned from God the most excellent of our doctrines, and the most holy part of our Law, by angels [Greek: “ambassadors”]” (Antiquities of the Jews, XV:163).

In summary, at the outset of his movement, it may be that Marcion was anti-Torah/temple cult/scribal system but not Anti-Yahweh or Anti-Jewish scriptures like the Psalms & Prophets (which also explains why the Pauline corpus and his Gospel are filled with references to the same)

I believe the “Anti-Thesis” (seen in Tertulian’s copy of Marcion) are later developed Marcionite traditions that evolved over time to be Anti-Yahweh (but were attributed to Marcion their founder).

You may know of the work of Markus Vinzent who is one scholar who argues that Marcion was not so much “anti” Jewish as a beleiver that there was a higher and better god than the “demiurge” who created the world. As for Jesus being the rock in 1 Corinthians, some argue that we have here a catholic addition to the original letter.

I am still inclined to (or unwilling to give up) the idea that Marcion’s gospel was the gospel of Mark.

Marcion’s use of the term ‘antithesis’ may provoke the concept of a complete divorce from Jewish customs, but I have in mind that Marcion is a clever theologian, and far more subtle than we give him credit for. The fact that his ‘Paul’ creation survives is a testimony to his ability to craft theology and narratives that bridge the divide.

I am not saying Marcion personally wrote gMark or the ‘authentic’ Pauls, I still think it is possible Marcion is the curator of works he brought from Asia Minor or Antioch. His Rome school no doubt continuing the Paul legacy.

I am thinking of the verse in Mark where Jesus says “for it is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs.”

It might be seen as Jesus testing the gentile woman to see her demonstrate her faith, but I think it might be actually a window into the original Jesus who was just a human carrying a divine spirit. The human Jesus is still a bigot who thinks his mission is to only help Jews. This Jesus is confronted by the faith and humility of the Gentile woman, he is surprised (how do you surprise an all knowing god-man?) and he is the one humbled here. We tend to project our ‘perfect divine Jesus’ into the story to try to explain this away, but if Mark is an earlier gospel, then Jesus does not have to be perfect.

This human Jesus is still learning on the job, and I can imagine that he could be the antithesis of the Jewish Messiah, as he progresses towards becoming the ultimate self-hating Jew when he prophecises against the temple and even rejects his own messianic destiny and his own body.

It would be interesting to re-evaluate the gospel of Mark to see if it really is anti-Marcionite. I tend to think the examples where Mark is said to be anti-Marcion often rely on a very literal interpretation of how Marcion’s theology is perceived, especially the supposed docetism model.

One little hitch to this idea is that no witness to the contents of Marcion’s gospel include the Syrophonician woman episode. Tertullian would appear to explicitly complain that Marcion “cut it out”.

I know some scholars say Mark’s Jesus is more human than the others — losing his temper, using spit and dirt to heal, healing in two stages — but they do so by ignoring the symbolic message of the healings and the fact that god himself (as well as good Stoics) could be quite entitled to express righteous anger. And walking on water is surely nothing less than a god-act.

As for the survival of Paul’s letters, I can’t see that they would have survived at all if they did not come with the gospels. They are a rather painful and scarcely coherent read on their own, don’t you think?

Yes, it is a problem if Tertullian says he ‘cut it out’.

Everything about Tertullian is a problem I think. I recall an article (which may have been on this site?) that argued that Tertullian did not even have a copy of Marcion’s gospel, and that he just inferred what Marcion ‘cut out’. I am not sure whether the same can be said about Epiphanius?

(I won’t link to the thread on that forum out of respect, but I note it is discussed there)

I think the whole missing gospel is in itself weird. The letters of Paul survived, but this Gospel didn’t? That in itself is not a big issue, if it weren’t for the supposed history of Marcionism surviving and flourishing for centuries after Marcion himself. Yet, I wonder if that is true also? Perhaps mistaken identity? Epiphanius seems to suggest they are still using this gospel? But even if they are direct descendants of Marcion’s cult, why would we assume they haven’t adapted their gospel since Marcion’s time? Maybe they did expurgate Luke and use this, but that could have happened a long time after Marcion, and Marcion’s original gospel had become obsoleted.

As for Paul’s letters having to exist with a gospel, I think there is something to that, especially with references to the gospels in the text. I wonder about “Jesus Christ was clearly portrayed as crucified”. Which to me suggests a gospel presented as a Greek drama. Obviously the writer has to infer the Galatians were not educated and had to have it this way, but there is no reason to think the schools themselves could not have used theatre as a means of communication as well. However, I think the limited references to an Earthly Jesus in Paul’s letters are still a hole for now. I imagine the writers of Paul’s letters do have a gospel in mind, but it is still a primitive gospel. That might be an argument for a primitive Marcion gospel.

I think the whole NL thesis does elevate the Marcion gospel as a crucial issue, as it must surely be a core work that somehow shaped the gospel evolution, even if it was superseded so quickly by what became Mark.

By the way – I am not saying Mark’s Jesus is not a god-man, but that he receives the spirit, so he was not born a god.

Regarding the absence of the Greek Syrophoenician woman episode from gLuke:

I think gLuke is a proto-orthodox revision of a gospel put together by the Simonian Cerdo and published by Marcion. But if so, why would Cerdo have left the episode out? Before I answer that, let’s look more closely at the episode and compare it to the version in gMatthew.

First, note that it is a bit strange that the woman is described as both a Greek/Hellene (Greek word “Hellenis”) and a Syrophoenician. Commentators usually say that Mark didn’t really mean that the woman was Greek; he just meant that she was not a Jew; that she was s Gentile. But I’m thinking, if that was the case why didn’t he just call her a Gentile? He knows the word for Gentile and uses it a couple of other places in his gospel, so why not here? Is there some reason he uses “Hellene” instead? And is this use connected in some way with why gMatthew replaced the whole “Hellene Syrophoenician woman” descriptive with “Canaanite woman”.

Next, as a number of commentators have noticed, “Here we meet for the first time a story which is longer and more vivid in Matthew than in Mark” (“The Earliest Records of Jesus”, by Beare, p. 132). That is to say, the things in gMatthew that he has in common with gMark are usually shortened by him but here, when he gets to chapter 15 of his gospel, we have a longer version. And one of the additional items are these words on the lips of his Jesus: “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Mt 15:24). The words could imply that the woman’s daughter was viewed by Jesus as a lost sheep, but not one that belonged to the house of Israel.

So, thus far the elements we have to work with are a Helene at Tyre in Phoenicia who may in some way be a lost sheep. When we add to the picture the common element of possession by a demon it begins to come into focus. For didn’t Simonians worship a Helen and claim that her pedigree went back in history to the Helen of Troy from which the Greeks were supposedly descended? And didn’t they claim that she was held in bondage by the spirit rulers of this lower world? And didn’t they claim that their Simon descended to this world to look for her and found her in a brothel at Tyre in Phoenicia? And didn’t Simonians refer to their Helen as the Lost Sheep?

But am I being too speculative, for surely there is nothing in the episode to suggest the woman’s daughter was a prostitute and her house a brothel. To which I would respond that there were lots of ways gMark could have described the daughter’s cure, for example, that the woman returned to her house and found her on her feet and well. But instead he brings in for the first time a bed. The woman finds her daughter “lying in a bed and the demon gone.” I know, I know, that’s pretty weak. Which is why I’ll add this: Readers of the episode have always been uncomfortable with its Jesus apparently referring to Gentiles as dogs. But I propose that he wasn’t actually doing that. He was referring to prostitutes as dogs, of which the woman’s daughter was one. In Greek the word dog can be used derogatively for a shameless woman (a bitch). It was often done so by Homer himself. And wouldn’t you know it, in the Iliad he has Helen apply the word to herself (Il. 6,344 and 356).

So, I am thinking the way to sort this all out is this:

The original Greek Syrophoenician episode was composed by the Simonian Basilides for his gospel. It honored the Simonian Helen as the Lost Sheep but was intentionally enigmatic, i.e., meant to be understood only by those on the inside. The episode was shortened and modified by the proto-orthodox when they revised Basilides’ gospel to make their gMark. Their removal of the Lost Sheep from the episode would seem to indicate that they had figured out its meaning.

Next came the Simonian Cerdo who expanded on the earlier work of Basilides. But because the proto-orthodox had already figured out and tampered with the Greek Syrophoenician, Cerdo decided to replace her and honor his Helen in a different way: He wrote the parable of the Lost Sheep and placed it in the Samaritan centraI section of his gospel. That parable underlines better the Simonian idea of Simon’s relentless search for the Lost Sheep and his great joy upon finding her. (Marcion subsequently published Cerdo’s gospel including the parable but I doubt that he was aware of its Simonian significance).

Next the proto-orthodox revised the gospel published by Marcion to produce their own gLuke. In doing so they kept the Lost Sheep parable but added a verse (Lk 15:7) at its end to make it look like the Lost Sheep referred not to a single individual but to anyone who repents of their sins. Commentators have often pointed out that the verse is secondary and the parable itself “is not concerned with penitence; the recovery of the sheep depends on the unwearied search for it by the shepherd, not on its own change of attitude “(“The Earliest Records of Jesus”, by Beare, p. 178).

Lastly, the proto-orthodox produced their own gospel, gMatthew. They did so with an awareness of the earlier texts and decided to keep – properly modified and sanitized — both the episode at Tyre and the parable of the Lost Sheep. And Matthew’s version of the episode, although it looks like an exception to his usual abbreviation of gMark, is not actually such. It is longer only because when the proto-orthodox had earlier reworked Basilides gospel to produce gMark they cut out more than usual.

Correction to my previous comment: the last name of the author of the book I quoted is Beare, not Beard. Full name: Francis Wright Beare

I corrected the original, by the way.

Yes, I do think you are on to something here. Interested readers should pair this comment with Roger’s earlier post: https://vridar.org/2016/05/05/a-simonian-origin-for-christianity-part-16-mark-as-allegory-2/

I have to confess: I find it a lot easier to believe there was an historical Jesus who died by crucifixion, and that some came to believe he’d been raised from the dead, and that this series of events happened in the early first century, and it was this Jesus that Paul was writing about in (roughly) the 50s CE.

Then what happened? Same thing that happens today, same thing that is happening in this thread: As time goes on, people start “revamping” an existing story so it says something they’d like it to say. I mean, in this thread alone, how many different ideas are we seeing?

Now, about this: “As for the survival of Paul’s letters, I can’t see that they would have survived at all if they did not come with the gospels. They are a rather painful and scarcely coherent read on their own, don’t you think?”

Paul’s letters are hardly a “rather painful and scarcely coherent read on their own” if the people that Paul was writing to already had “background info” concerning what Paul was writing about. Now, if I didn’t know anything at all about somebody named “Jesus” who died by crucificixion, and was believed to have been raised from the dead, then, yeh, reading Paul’s letters could prove to be difficult to comprehend. It would be like stepping into the middle of someone else’s conversation about something I know nothing about in the first place. But, if Paul was writing to already-established “churches” that had formed around the belief that there was a “real Jesus” who died and was raised from the dead, then, no, those letters wouldn’t, by any necessity, be difficult for those recipients to understand.

Just a thought…

Unfortunately it goes against all we know about how stories about historical persons grow. Further, the view you present asks us to believe the most unlikely: that Jews would over time come to believe that a crucified prophet was god incarnate. Further, it goes against all the norms we have for determining this or that person or event was historical: the story is not independently confirmed until a century after the time of Jesus and it provides no assurances of its historicity. This is not how we determine the historicity of any other event or person in ancient (or modern) times.

As for Paul’s letters having some meaning for their original audiences, of course they would be meaningful for them (but see the posts on Livesey’s book). But my point is that they would not be preserved and held in esteem to anyone else without the context of the gospel stories — and Acts.

re: “Unfortunately it goes against all we know about how stories about historical persons grow”

If Paul was writing in the 50s about an historical Jesus who was believed by some to have been raised from the dead, you think that couldn’t have grown into a story of a Jesus who walked on water and fed 5000 people on a limited food budget?

I realize there are many who want to believe that the “resurrection story” was more-or-less on the “tail end” of stories about a fictitious character that developed over time. Like, “there was once a guy named Jesus who could heal the sick” got added to, so it became “there was a guy name Jesus who could heal the sick, and he could even walk on water”, and that became “healed the sick, walked on water, and in the end he was raised from the dead”. But, I think it was the other way around. Somebody believed Jesus, a guy who was (perhaps) a “beloved rabbi”, was “raised from the dead”, and *that* led to stories about how he healed the sick and walked on water and fed 5000 people on a limited food budget (and others).

Why do I say that? Because there are people these days that say “Elvis lives” and “Jimmy Hoffa was abducted by aliens” and “Amelia Earhart disappeared into another dimension”. People can very easily say really strange things about dead people. Even now, in modern, educated cultures. So I don’t think it’s remotely unimaginable that somebody said that an historical Jesus who died had been raised from the dead. And I think that it was from that, that other stories (like, stories of walking on water, etc) about Jesus grew.

re: “Further, the view you present asks us to believe the most unlikely: that Jews would over time come to believe that a crucified prophet was god incarnate. ”

I can’t even begin to imagine why you say that. I mean, the lion’s share of Jews certainly never came to believe a prophet was god incarnate. If there were any that ever came to believe that, they were a tiny minority of exceptions.

The thing is, I don’t even think Paul considered Jesus to be “god incarnate”. I think Paul considered “Messiah” to be divine in some sense, but, not “god incarnate”. That whole idea of “god incarnate” appears to me to have been one that developed over time, as the story spread into Greek cultures. So, I just don’t know why you think the “historical Jesus” that Paul wrote about somehow necessitates Jews believing a prophet was “god incarnate”.

re: “Further, it goes against all the norms we have for determining this or that person or event was historical”

Evidently, the idea that Jesus was an historical person does NOT go against any “norms” we have for determining this or that person or event was historical, because it’s HISTORIANS who have determined that Jesus an historical person, based on whatever “norms” they employ.

If you think those “norms” currently in use are unacceptable, then that’s fine. But when about 99.5% of historians that deal with NT/Jesus-related history all agree that Jesus existed as an historical person, then it must be quite clear that the “norms” they employ lead them to such an agreement. If their scholarly consensus on the matter wasn’t in line with the “norms” they employ, then, there wouldn’t be a scholarly consensus, would there?

Again – if you wish to say that those “norms” should NOT be the “norms”, then that’s perfectly fine with me. Correct the “norms”, if you must, then let me and everyone else know what the “new norms” are.

As things now stand, though, I find it far easier to believe there was an historical Jesus who was believed, by some, to have been raised from the dead, and that an historical Paul was writing about that particular Jesus.

Well, no less a scholar than Bart Ehrman himself wrote and declared that biblical historians have always simply assumed there was a historical Jesus. The question, as far as he knew (he wrote), had never been seriously investigated by “historians”.

It is always easier to assume anything than to demonstrate and argue a case.

https://ehrmanblog.org/did-jesus-exist-as-part-one-for-members/

(I have quoted what other real historians — not theologians — have had to say about the methods of biblical scholars but I don’t think you would appreciate reading those observations.)

What Ehrman said was this: “even though experts in the study of the historical Jesus (and Christian origins, and classics, and ancient history, etc etc.) have known in the back of their minds ALL SORTS OF POWERFUL REASONS for simply assuming that Jesus existed, no one had ever tried to prove it. Odd as it may seem, no scholar of the New Testament has ever thought to put together a sustained argument that Jesus must have lived. To my knowledge, I was the first to try it, and it was a very interesting intellectual exercise. How do you prove that someone from 2000 years ago actually lived? I have to say, it was terrifically enlightening, engaging, and fun to think through all the issues and come up with all the arguments. I THINK REALLY ALMOST ANY NEW TESTAMENT SCHOLAR COULD HAVE DONE IT”.

(Perhaps needless to say, the CAPS are mine, for emphasis).

There is no assertion on Ehrman’s part that Jesus’ existence was “merely assumed”. He states that although experts in the field “have known in the back of their minds ALL SORTS OF POWERFUL REASONS for simply assuming that Jesus existed, NO ONE EVER TRIED TO PROVE IT”.

(Again, CAPS are mine).

The point? What Ehrman says is a far cry different from how you’re trying to represent it, IMHO. I mean, Ehrman IS the guy that wrote the book “Did Jesus Exist” in which he does make the case for the existence of Jesus, and he’s likewise the guy that said “really almost any New Testament scholar could have done it”.

re: “I have quoted what other real historians — not theologians — have had to say about the methods of biblical scholars but I don’t think you would appreciate reading those observations”.

What makes you think I haven’t read your views on what “other real historians” have to say about the methods of biblical scholars? Not only have I read considerable writings of yours, I’ve read writings on the same topics written by some of those historians.

I clearly said in my earlier msg, “Again – if you wish to say that those “norms” should NOT be the “norms”, then that’s perfectly fine with me. Correct the “norms”, if you must, then let me and everyone else know what the “new norms” are.”

But, until and unless those “norms” – the methods of biblical scholars – have changed such that everyone is working with the same, updated methodology, then we’re stuck with a majority – many of whom are quite aware of the shortcomings of the current methodologies – still convinced that there was an historical Jesus and, for that matter, an historical Paul.

Then why did Bart Ehrman not simply tell readers what these “powerful reasons in the backs of theologians’ minds” were instead of writing up a lot of made-up off-the-cuff nonsense, riddled with circularity and other basic logical fallacies and a methodology that would not even pass muster among many of his peers today?

Telling us that other people had “reasons in the back of their minds” for the assumptions they made may impress you — but assumptions of any kind need to be justified explicitly (not hidden away and never even spoken) and assumptions of any kind are not sufficient for establishing any event or person as historical. If scholars had never brought forth their reasons from the backs of their minds that is tantamount to saying they never addressed the arguments they ought to have addressed.

Try passing any exam by telling your examiner that you “have reasons in the back of your mind” to justify your conclusion. That’s not how the real world or any scholarly conclusion works.

Having reasons in the BACK OF ONE’S MIND for ASSUMING such and such is not a scholarly standard of argument or sound basis of any argument. It is simply another way of saying “I assume” but “feel I can come up with justifications if pressed” — “something in the back of my mind” will come to my rescue, “I am sure of it!”.

Every time we ASSUME something we ASSUME BECAUSE we feel we have “reasons in the back of our minds” for making an assumption. That’s why we assume in the first place.

To get over assumptions we need to test what’s “in the back of our minds”.

In other words, Ehrman said he was the first, as far as he knew, to actually set out the case for the historicity of Jesus. But if you found any logic or standard or “norm” used by other historians in anything Ehrman wrote about the historicity of Jesus then do share it here. Erhman broke every rule and every “norm” of historical inquiry as practised among mainstream historians in his book. He simply repeated the nonsense and circular methods that have no place in mainstream history departments.

Okay — but if you must have a fight, then tell me exactly what are the “norms” of historians to which you refer? Or do you mean the “norms” of biblical scholars? Are they the same as those of “historians”?

re: “Then why did Bart Ehrman not simply tell readers what these “powerful reasons in the backs of theologians’ minds” were instead of writing up a lot of made-up off-the-cuff nonsense, riddled with circularity and other basic logical fallacies and a methodology that would not even pass muster among many of his peers today?”

Wait. You’re seriously asking me to speculate as to why Ehrman didn’t make a comment about THEOLOGIANS???????

I’ve got no idea of why he didn’t comment about theologians. All I know is that he commented about “experts experts in the study of the historical Jesus (and Christian origins, and classics, and ancient history, etc etc.)”. And, the last I checked, Ehrman himself is considered one of those experts.

His point is that while there were “strong reasons” for the experts to “assume” the existence of an historical Jesus, “no scholar of the New Testament has ever thought to put together a sustained argument that Jesus must have lived.”

That, of course, includes Ehrman himself. So, he decided to put together a sustained argument that Jesus must have lived, in the form of a book called “Did Jesus Exist?”. And, he remarks that ” I think really almost any new testament scholar could have done it”. Why? Because they already have all the same info that Ehrman put together in his book.

re: “In other words, Ehrman said he was the first, as far as he knew, to actually set out the case for the historicity of Jesus.”

WRONG. That is NOT what he said. He said “Odd as it may seem, no scholar of the New Testament has ever thought to put together a sustained argument that Jesus must have lived”.

OBVIOUSLY, there have been many arguments made over time in favor of the historicity of Jesus, and that’s why there is a Scholarly Consensus that there was an historical Jesus who was baptized by John the Baptist, and who died by crucifixion under orders of Pontius Pilate. The overwhelming majority of scholars that deal with NT/Jesus-related studies agree with it. But, nobody ever sat down to write out a “sustained argument that Jesus must have lived”, which simply means nobody has ever sat down and written a book like “Did Jesus Exist” before.

Look, Neil, if your arguments are going to rely on misquotes, then, there’s something wrong with your arguments.

I really enjoy reading what you write in your blog posts, but, this kind of interaction, dealing with “straw men” (created by your misquotes) is just not my cup of tea.

You want to argue over Ehrman’s use of the word “assume”? I don’t. I’m happy to let you have your opinion on the matter, and I’ll have mine.

As far as the “norms” I referred to earlier, I’m referring to WHATEVER those “norms” (or methodologies) currently in use are. I never said they were acceptable, or of the best quality, or any such thing. In fact, I even said ““Again – if you wish to say that those “norms” should NOT be the “norms”, then that’s perfectly fine with me. Correct the “norms”, if you must, then let me and everyone else know what the “new norms” are.”

I do not believe I have at all misquoted anything by Bart Ehrman. But we draw different interpretations or meanings from his words. I have read enough of the scholarship, the overwhelming majority of it by theologians (not people with specialist training in history as would be recognized by historians in non-biblical history departments) to know that most who write about the historical or any other kind of Jesus simply do not indicate any interest in following the methods of historians.

Yes, they DO nearly all simply ASSUME there is a historical Jesus to write about. When — on the very rare times they actually do — when they address the question of how they know Jesus existed they simply repeat the notion that the gospels could only have been put together after a record of oral tradition being passedd on from the time of Jesus. They all assume the letters of Paul — at least much of their core — are genuine.

Ehrman is right. Scholars have simply assumed — and no doubt they have felt that “if” they were to be called on to justify their assumption, they would be able to find reasons.

If you can point me to any book or books about the historical Jesus that does not begin with such an assumption, I would be most interested. No doubt there must be some — I have not read everything.

You trust too much. No, the only arguments mounted for a historical Jesus have been those that have specifically been composed to address the “mythicists” of the past. Surely Ehrman must have known about these but they evidently slipped his mind — and minds of anyone peer-reviewing or editing his book. All their arguments reduce to misrepresentations of the mythicist case of their day or resort to logical fallacies such as outright circular reasoning. If you can give me any exceptions then please do so — this time I have read most of those particular works.

This is not must my opinion. That circularity and unargued assumptions have been at the heart of biblical studies — both for OT and NT — has been noted and pointed out in published works by a handful of scholars themselves.

(I will address the “norms” of historians in another comment here. They are well known. Books have been written about them.)

Just a little background ….. Bart Ehrman has come to rely on his well publicized reputation more than any serious scholarship, unfortunately. It is not only in relation to the question of Jesus’ historicity, either. When he attempted to “cash in” (I think the term is appropriate) on the current memory theory discussions about the historical Jesus he wrote as if he had never heard of the theoretical and technical debates about the topic and that had been published in abundance before him. If it were not for his reputation I can’t imagine his work even being published. He wrote a book on the question of Jesus’ existence and in his work he left clear indicators he had not even read the works he supposedly criticized. His book is an embarrassment for its fundamental logical fallacies throughout and his grossly misleading claims about the Christian sources for Jesus. I cannot imagine any scholar of a lesser reputation getting away with such fallacious and ignorant work. Am I saying Ehrman is a fraud? I am saying he has produced fraudulent work.

Ehrman is not honest. He misleads. He writes things that are simply not so and that he ought to know. Of course he is going to try to make it sound like scholars have had “powerful reasons in the back of their minds” for the hitoricity of Jesus because its in that field where he has made his reputation. But such a claim is meaningless. If reasons have been kept in the backs of minds then they have never been published or tested — and Ehrman would surely know of some of them and say exactly what they are. Instead he made silly claims about photographs that are entirely circular. He said we have multiple independent sources whose contents can be traced back to Jesus — an outrageously false claim. He can get away with all this simply because of his high reputation.

I learned long ago to always check claims, never assume. Richard Carrier is another who relies on his reputation among a certain public to pass off misleading claims. Scholars sometimes do that. There is nothing “obvious” about their claims unless they set the claim unambiguously beside the evidence for it. If the evidence exists, most scholars will cite it to verify their claim. When they don’t cite the evidence then we have a right to be suspicious and an obligation to look for it before repeating their claim as a fact.

There are many excellent biblical studies scholars and many excellent published works by them. But there is also a sector that is fundamentally apologetic and without any serious intellectual rigour at its foundations. Even the “token atheist” scholars in this field have found an easy way “to earn” their lunch.

Ehrman wrote about the absence of a single, comprehensive, dedicated work solely focused on proving Jesus’s existence. By way of example, historians rarely if ever write books titled “Caesar Actually Existed.” They assume the existence of certain historical figures and focus on analyzing their lives and impact. Ehrman is claiming that Jesus’s existence has been so widely accepted within scholarly circles that a dedicated, book-length defense of it has not been ever been written before.

What one often finds in in-depth studies of historical persons is an introductory preface or such informing all readers of the sources on which the historian is relying and how the historian knows about the historicity of such and such events and persons. When they think of historical figures they think in terms of sources, of questions of the reliability of various sources, and so forth.

There are books written for prospective higher degree students of history in which these sources are discussed along with “how we know what we know” about the manuscripts etc, and the kinds of questions historians are expected to ask of the various sources they use. I know of nothing comparable in the studies of the historical Jesus — unless we count assumed sources like Q and oral tradition and memory trails.

Thankyou for posting my comment. What I was attempting to suggest is that the template was already existing. Others have said this I know, but I come back to it as I see it as an essential piece that explains most everything. The Logos/Great Angel/heavenly Adam emanation was widely accepted. The Jewish god/man did not need to be invented.

Regarding the repeated ‘spit’ of Mark used to heal. The writer likely was simply drawing from a common belief of spit’s medicinal value (Galen and Tacitus relate stories) but may have had again a symbolism of ‘baptism’ or ‘spoken’ teaching implied. Both concepts were associated with spit.

For me the question is not whether it was possible for an historical rogue Rabbi to have been deified (or interpreted as a manifestation of the Logos) after death, because of course that is so. There were also many deities that were euhemerized/incarnated as well. The issue as I see it is what best fits the evidence. For me the fact that there are no biographical details not derived/contrived from the OT typology, no contemporary references to him among the many would-be messiahs and thirdly the mystical/nonphysical Christologies that existed at the earliest stages together suggest an original revelatory Christ formulation.

Ultimately the issue is moot, if there was a person/s (John the Bapt, Simon Magus, The Jesus who pronounced woes of Jerusalem/killed with a catapult, Teacher of Right. etc.) that became enveloped in the Son of God myth, he left so little an impression on the writers that nothing in the story can be connected to him specifically. I have challenged others on another forum to give one unique aspect of the teaching or one biographical detail that we must regard as historical, and the results of analyzing them were very telling. There is nothing.

What is this forum?

I am glad, Neil, that you appear at last to be abandoning the idea that despite accepting that the Gospels, Pauline (and pseudoPauline) letters, and the Revelation to John, are 2nd century CE texts, Christianity is a 1st century CE religion. Not that I agree with you that the texts are all so late, but if that is accepted, then it becomes easier to accept that Christianity was likewise 2nd century CE – especially when one accepts that Hebrews was post-70CE.

A Buddhist…I anonymously posted on a Christian cult recovery forum for 2 decades.

I just can’t get behind the radikal conclusion that all our material is second century.

The existence of Luke and the many other recensions and even Gospel harmonies by the mid second century requires we accept a first century date for Mark at least. Paul’s work seems to have been reworked at least twice by the second century, which also suggests he was active much earlier. IMO it might be more likely sects merging the Akedah drama with the Logos concept arose as early as a century before. The persuasive proposal that Mark was a transcript of a play also suggests that by the time the play was produced there was an audience. All this pushes “Christian” origins back not forward in time.

Great post, Neil. That “winner” or “revolutionary moment” you speak of was, in my opinion, proto-orthodox. I think they must be given the credit, not the Simonians, even though these latter were earlier than they and provided them with so much material that they were able to modify and use. The Simonians appear to have just been looking to inject their beliefs into the beliefs of all their neighbors. I don’t think they were really looking to create anything new. Marcion, on the other hand, did want to create a new church using the material supplied to him by Cerdo, but the connection to the Jewish Scriptures was too tenuous to last. It was the proto-orthodox who came up with the winning combination.

The way I read Justin Martyr’s Trypho is to imagine a potpourri of allegorical essays floating around with various functions — some of which were selected, others refined, for a subsequent narrative. What still bemuses me is the rationale for the scenario of the Jordan bursting into flames when Jesus enters to join John.

Justin’s baptism scene is certainly more exciting than the usual Canonical version. A little digging online revealed similar traditions were evidenced from the 2nd century and continued for centuries.

A 6th century hymn on the Epiphany by Romanos Melodos, XVI.14.7-10

“and fire in the Jordan shining”

Ephrem’s commentary on the Diatessaron and Ishodad of Merv both declared that in an early version of the Diatessaron the words appeared:

“… light shone forth, and over the Jordan was spread a vail of white clouds, and there appeared many hosts of spiritual beings who were praising God in the air; and quietly Jordan stood still from its flowing, its waters being at rest; and a sweet odor was wafted from thence.

Kerygma Pauli (Preachings of Paul) “…when he was baptized, fire appeared upon the water.”

The 3 century “De rebaptismate” describes a group of Christians who included fire in their baptism ceremony following the above Kerygma Pauli.

The Gospel of the Ebionites: “and immediately a great light shone around the place”

Gregory of Antioch (6th CE) notes the fire on the Jordan in his Homilia in S. Theophania.

And two Old Latin mss (ita vgms) of Matthew 13:

And when Jesus was being baptized a great light flashed (a tremendous light flashed around) from the water, so that all who had gathered there were afraid

There are apparently many more examples.

Obviously, the symbolism of light and fire are in play.

Often the metaphor or parable was converted into a narrative, as two sides the same coin.

I must correct my last comment. De rebaptismate describes a baptism involving fire attributed to Simonians. Just how we define ‘Christian’ comes to the fore again.

It seems clear there was much shared between those who adored Simon and Helene and those who used the names ‘Jesus’ and Mary.