Here I continue a series I began in July 2010 — a history of the Zionist movement as documented from official archives and personal diaries by the Palestinian historian Nur Masalha.

I have long held off from completing that task, most especially since recent events in Gaza and now the West Bank and Lebanon left me feeling that the current traumas are too suffocating to allow anyone to think of the past. But the past is important for understanding what is happening today.

The following account makes it clear why current events did not begin with the Hamas attack on October 7 2024. It will all sound so horrifyingly familiar that you that you may find yourself wondering if you are reading history or today’s news stories.

| “What did the world do to prevent the genocide of the Jews? Why now should there be such excitement about the plight of the Arab refugees?“ |

The “Miracle” of the “Arab Exodus”

We may have heard that Arabs fled wholesale of their own free will when the state of Israel was declared in May 1948.

The plight of these Arab refugees and the problem they posed deserve attention . . . A huge and pitiful multitude, uprooted, exploited and helpless, they numbered at their height approximately 750,000. . . .

Superstitious and uneducated, the Arab masses succumbed to the panic and fled. . . .

Certainly, [the big three — Weizmann, Ben-Gurion or Sharett] had been quite unprepared for the Arab exodus; no responsible Zionist leader had anticipated such a “miraculous” clearing of the land. Dr. Weizmann, despite his ingrained rationalism, spoke to me emotionally of this “miraculous simplification of Israel’s tasks,” and cited the vaster tragedy of six million Jews murdered during World War II. He would ask, “What did the world do to prevent this genocide? Why now should there be such excitement in the UN and the Western capitals about the plight of the Arab refugees?” — First United States Ambassador to Israel, James G. McDonald, p. 174ff

Such a carefully worded narrative positions the Arab “exodus” of 1948 as a sadly inferior foil to the biblical Jewish exodus, even a matter of divinely ordained compensation for one party at the “tragic” expense of “pitiful, superstitious, cowardly masses”. MacDonald does elsewhere express some pity for the Arabs along with regret that the Israeli approach was not “more humane”. But the purpose of these posts is to cite what the Israeli leadership were in fact thinking and planning — how the Zionist program planned for and enforced the Arab evacuations.

Events leading to the 1948 Exodus

Let’s back up a few months and into the year before Israel declared its actual birth.

2 November 1947: A vote by the United Nations General Assembly was imminent. The UN was scheduled to declare that Palestine should be partitioned between Jews and Arabs and that the Jewish state would contain a large Arab population (42%). The leading Zionist organization, the Jewish Agency Executive, met and agreed that citizenship should not be granted to the Arabs in the soon-to-be-established Jewish state. The reason was stated by Ben-Gurion:

In the event of war between the two Palestine states, said Ben-Gurion, the Arab minority in the Jewish State would be ‘“‘a Fifth Column.”’ Hence, it was best that they be citizens of the Palestine Arab State so that, if hostile, they “‘could be expelled”’ to the Palestine Arab State. But if they were citizens of the Jewish State, “‘it would only be possible to imprison them, and it would be better to expel them than to imprison them.”’ (Benny Morris, 28, citing the minutes of the Jewish Agency Executive meeting)

29 November 1947: The United Nations General Assembly passed resolution 181 endorsing the partition of Palestine into 2 states: Arab and Jewish, with Jerusalem and Bethlehem forming an international zone. The boundaries drawn up meant the Jewish state would consist of a 42% Arab population.

30 December 1947: Ben Gurion addressed the Histadrut and declared that the Zionist settlers of Palestine would need to learn to think “like a state”:

There can be no stable and strong Jewish state so long as it has a Jewish majority of only 60 percent.

This, Ben-Gurion added, made necessary the adoption of “a new approach…new habits of mind to suit our new future. We must think like a state.” (Masalha, 176; Morris, 28)

But what kind of state should Israel “think like”?

The kind of state in Ben-Gurion’s mind was Turkey which had ethnically cleansed (or “transferred”) their Greek population. Eleven years earlier he had made it clear that there was “nothing morally wrong in the idea” but that it was the kind of thing only a state should carry out.

[Two non-Zionists, Senator and Hexter] vehemently opposed the transfer idea: ’there are Arabs in this country. The more we take them in consideration, the more we will succeed . . . .’ Senator considered transfer as fraught with danger: ‘We can’t say that we want to live with the Arabs and at the same time transfer them to Transjordan.’ In summing up the debate, Ben-Gurion stated that . . . the population exchange between Greece and Turkey could not serve as a precedent since it was a pursuant to voluntary agreement between two states: ‘We are not a state and Britain will not do it for us . . In Ben-Gurion’s view, the proposal would alienate public opinion, including Jewish public opinion, but there is nothing morally wrong in the idea’. (Flapan, 261)

We have encountered Turkey’s expulsion of the Greeks before as a debated model among early Zionists: Zionist Plans (1936); Pushing for Mass Transfer (1937); Compulsory Arab Transfer (1937); Caution and Discretion (1941).

Conflict Begins Before Israel’s Foundation in May 1948:

Within weeks of the UN partition resolution, the country was plunged into what soon became a full-scale civil war. By mid-December, “spontaneous and unorganized” Palestinian outbreaks of violence were being met by the full weight of the Yishuv’s armed forces, the Haganah, in what the British high commissioner called “indiscriminate action against the Arabs,”3 coupled with measures aimed at economic strangulation. Ben-Gurion advised on 19 December that “we adopt the system of aggressive defense; with every Arab attack we must respond with a decisive blow: the destruction of the place or the expulsion of the residents along with the seizure of the place.”4 On 30 December, a British intelligence observer reported that the Haganah was moving fast to exploit Palestinian weaknesses and disorganization, especially in Haifa and Jaffa, and to render them “completely powerless” so as to force them into flight.

The Palestinians were completely unprepared for war, their leadership still in disarray and largely unarmed as a result of the 1936-39 rebellion. The Yishuv’s defense force, the Haganah (to say nothing of the dissident Irgun Tzvai Leumi and Lehi groups), was fully armed and on the offensive. As early as February 1945, before World War II had even ended, the first of a series of master military plans adopted by the Haganah (which in turn was under the jurisdiction of the Jewish Agency) was in place in anticipation of the war for statehood. (Masalha, 176f. Note 3 = Middle East Centre, St. Antony’s College Archives, Oxford, Cunningham Papers, 1/3/147, “Weekly intelligence Appreciation.” A three-day general strike started on 2 December in protest of the United Nations resolution. Note 4, see quote from Flapan p 90 following…)

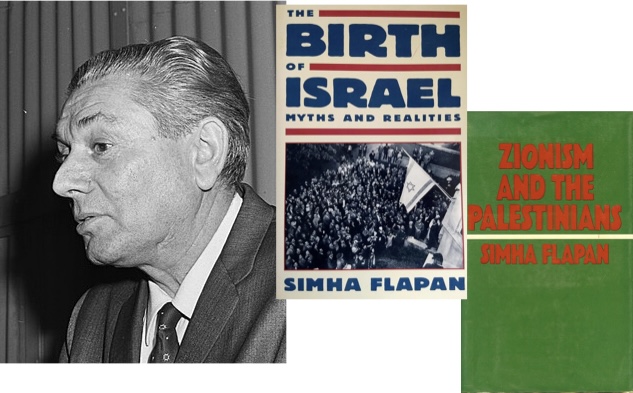

I flip over from Nur Masalha’s account to that of Simha Flapan, The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities, beginning from page 88 (with my highlighting and formatting):

Records are available from archives and diaries, however, and while not revealing a specific plan or precise orders for expulsion, they provide overwhelming circumstantial evidence to show that a design was being implemented by the Haganah, and later by the IDF, to reduce the number of Arabs in the Jewish state to a minimum, and to make use of most of their lands, properties, and habitats to absorb the masses of Jewish immigrants.

89

It is true, of course, that many Palestinians left of their own accord. Tens of thousands of community leaders, businessmen, landowners, and members of the intellectual elite who had the means for removing their families from the scene of fighting did so. Thousands of others — government officials, professionals, and skilled workers chose to immigrate to Arab areas rather than live in a Jewish state, where they feared unemployment and discrimination. Nearly half the Arab population of Haifa moved to Nazareth, Acre, Nablus, and Jenin before their city was captured by the Haganah on April 23, 1948. The Arab quarters of Wadi Nisnas and Karmel were almost completely emptied out. . . .

But hundreds of thousands of others, intimidated and terrorized, fled in panic, and still others were driven out by the Jewish army, which, under the leadership of Ben-Gurion, planned and executed the expulsion in the wake of the UN Partition Resolution.

The balance is clear in IDF intelligence estimates. As of June 1, 1948, 370,000 Arabs had left the country, from both the Jewish parts and the Arab parts conquered by the Jews.

-

-

- Jewish attacks on Arab centers, particularly large villages, townlets, or cities, accounted for about 55 percent of those who left;

- terrorist acts of the Irgun and LEHI, 15 percent;

- whispering campaigns (psychological warfare), about 2 percent;

- evacuation ordered by the IDF, another 2 percent;

- and general fear, about 10 percent.

-

Therefore, 84 percent left in direct response to Israeli actions, while only 5 percent left on orders from Arab bands. The remaining 11 percent are not accounted for in this estimate and may refer to those who left voluntarily. (The total reflects only about 50 percent of the entire exodus since a similar number were to leave the country within the next six months.)

Again, it is obvious that no specific orders for expulsion could have been issued. All of the Zionist movements’ official pronouncements as well as those of the provisional government and, after January 1949, the Israeli government — and Ben-Gurion was prominent in these bodies — promised, as noted, fair treatment for the Arab minority. Moreover, in the face of the often brutal destruction and evacuation of villages, Ben-Gurion — along with other cabinet ministers — publicly criticized the brutality, looting, rape, and indiscriminate killing.

90

In private, however, Ben-Gurion was not averse to making his real views clear. Thus, on December 19, 1947, he demanded that “we adopt the system of aggressive defense; with every Arab attack we must respond with a decisive blow: the destruction of the place or the expulsion of the residents along with the seizure of the place.” He declared: “When in action we . . . must fight strongly and cruelly, letting nothing stop us.’’ Even without direct orders, the goal and spirit of real policy were understood and accepted by the army. That Ben-Gurions’ ultimate aim was to evacuate as much of the Arab population as possible from the Jewish state can hardly be doubted, if only from the variety of means he employed to achieve this purpose:

-

-

- an economic war aimed at destroying Arab transport, commerce, and the supply of foods and raw materials to the urban population;

- psychological warfare, ranging from “friendly warnings” to outright intimidation and exploitation of panic caused by dissident underground terrorism;

- and finally, and most decisively, the destruction of whole villages and the eviction of their inhabitants by the army.

-

Ben-Gurion took note of the combined effects of economic, military, and psychological warfare in a diary entry from December 11, 1947:

Arabs are fleeing from Jaffa and Haifa. Bedouin are fleeing from the Sharon. Most are seeking refuge with members of their family. Villagers are returning to their villages. Leaders are also in flight, most of them are taking their families to Nablus, Nazareth. The Bedouin are moving to Arab areas. According to our “friends” [advisers], every response to our dealing a hard blow at the Arabs with many casualties is a blessing. This will increase the Arabs’ fear and external help for the Arabs will be ineffective. . . . Josh Palmon [an adviser to Ben-Gurion on Arab affairs] thinks that Haifa and Jaffa will be evacuated [by the Arabs] because of hunger. There was almost famine in Jaffa during the disturbances of 1936-1939.

91

In a letter to Sharett a few days later, Ben-Gurion focused on economic issues, observing that “the important difference with [the riots of] 1937 is the increased vulnerability of the Arab urban economy. Haifa and Jaffa are at our mercy. We can ‘starve them out.’ Motorized transport, which has also become an important factor in their life, is to a large extent at our mercy.”

The destruction of the Palestinian urban bases, along with the conquest and evacuation (willing or unwilling) of nearby villages, undermined the whole structure of Palestinian life in many parts of the country, especially in the towns. Ben-Gurion’s advisers urged closing stores, barring raw materials from factories, and various other measures.

-

-

- Yadin, the army’s head of operations, advised that “we must paralyze Arab transportation and commerce, and harass them in country and town. This is the way to lower their morale.”

- And Sasson proposed “damaging Arab commerce — even if Jewish commerce will be damaged. We can tolerate it, they cannot. . . we must not hit here and there, but at all transportation at once, all commerce and so on.”

- Ezra Danin spoke of “a crushing blow” to be dealt by destroying “transportation (buses, trucks transporting agricultural produce, and private cars) . . . [and] economic facilities — Jaffa port (boats to be sunk); the closing down of stores; cutting off their contact with neighboring countries; the closing down of Arab factories through blockage of raw materials and cement.” Later, he added that “Jaffa must be put under a state of siege.” . . . .

- Yigal Allon, commander in chief of the Haganah’s Palmach shock troops, also advised economic measures: “It is not always possible to discern between opponents and nonopponents. . . . It is impossible to refrain from injuring children — because it is impossible to separate them from the others when one has to enter every house. The Arabs are defending themselves now, and there are weapons in every house. Now only extreme punitive measures are possible. The call for peace will appear as a sign of weakness. Only after inflicting a major blow can calls to peace work. We must strike at their economy.”

-

Clearly, significant numbers of Arabs without food, work, or the most elementary security would choose to leave, especially given that almost all of their official leadership had left even before the fighting began.

92

On January 5, 1948, Ben-Gurion was able to review in his diary some of the effects of economic warfare on the Arabs of Haifa: “[Their] commerce has for the most part been destroyed, many stores are closed . . . prices are rising among the Arabs.” He noted that up to twenty thousand Arabs had left, including many of the wealthier people, whose businesses were no doubt among those destroyed.

Ben-Gurion’s belief in the efficacy of the policy of destroying the Arab economy led him to monitor its results constantly. Thus, on January 11, 1948, he noted in his diary a telephone conversation between Hussein al-Khalidi, secretary of the Arab Higher Committee and former mayor of Jerusalem, and the banker Farid Bey, in Haifa. Farid Bey told Khalidi of the desperate situation in Jerusalem and Haifa. “You have no idea how hard it is outside,” Khalidi replied, referring to the Arab leadership abroad. Farid Bey responded, “And here [Arabs] are dying day by day.” “It is even worse in Jaffa,” said Khalidi. “Everyone is leaving.”

That same day, Sasson reported to King Abdallah that the Palestinians in Haifa, Jaffa, and Jerusalem were facing “hunger, poverty, unemployment, fear, terror.” Two days later, on January 13, Khalidi informed the mufti of the crisis: “The position here is very difficult,” he reported from Jerusalem. “There are no people, no discipline, no arms, and no ammunition. Over and above this, there is no tinned food and no foodstuffs. The black market is flourishing. The economy is destroyed. . . . This is the real situation, there is no flour, no food. . . . Jerusalem is emptying out.”

The urban disintegration of the Palestinian Arabs was a fait accompli. Ben-Gurion’s tactics had succeeded. As he explained it:

The strategic objective [of the Jewish forces] was to destroy the urban communities, which were the most organized and politically conscious sections of the Palestinian people. This was not done by house-to-house fighting inside the cities and towns, but by the conquest and destruction of the rural areas surrounding most of the towns. This technique led to the collapse and surrender of Haifa, Jaffa, Tiberias, Safed, Acre, Beit-Shan, Lydda, Ramleh, Majdal, and Beersheba. Deprived of transportation, food, and raw materials, the urban communities underwent a process of disintegration, chaos, and hunger, which forced them to surrender.

93

The military campaign against the Arabs, including the “conquest and destruction of the rural areas,” was set forth in the Haganah’s Plan Dalet [which I will outline in my next post]. Plan D, formulated and put into operation in March 1948, went into effect “officially” only on May 14, when the state was declared. The tenets of the plan were clear and unequivocal: The Haganah must carry out “activities against enemy settlements which are situated within or near to our Haganah installations, with the aim of preventing their use by active [Arab] armed forces.” These activities included the destruction of villages, the destruction of the armed enemy, and, in case of opposition during searches, the expulsion of the population to points outside the borders of the state.

Also targeted were transport and communication routes that might be used by the Arab forces. According to an interview with Yadin some twenty-five years later, “The plan intended to secure the territory of the state as far as the Palestinian Arabs were concerned, communication routes, and the strongholds required.” Yadin and his assistants outlined nine courses of operation that included “blocking the access roads of the enemy from their bases to targets inside the Jewish state,” and the “domination of the main arteries of transportation that are vital to the Jews, and destruction of the Arab villages near them, so that they shall not serve as bases for attacks on the traffic.”

The plan also referred to the “temporary” conquest of Arab bases outside Israeli borders. It included detailed guidelines for taking over Arab neighborhoods in mixed towns, particularly those overlooking transport routes, and the expulsion of their populations to the nearest urban center.

The psychological aspect of warfare was not neglected either. The day after the plan went into effect, the Lebanese paper Al-Hayat quoted a leaflet that was dropped from the air and signed by the Haganah command in Galilee:

We have no wish to fight ordinary people who want to live in peace, but only the army and forces which are preparing to invade Palestine. Therefore . . . all people who do not want this war must leave together with their women and children in order to be safe. This is going to be a cruel war, with no mercy or compassion. There is no reason why you should endanger yourselves.

94

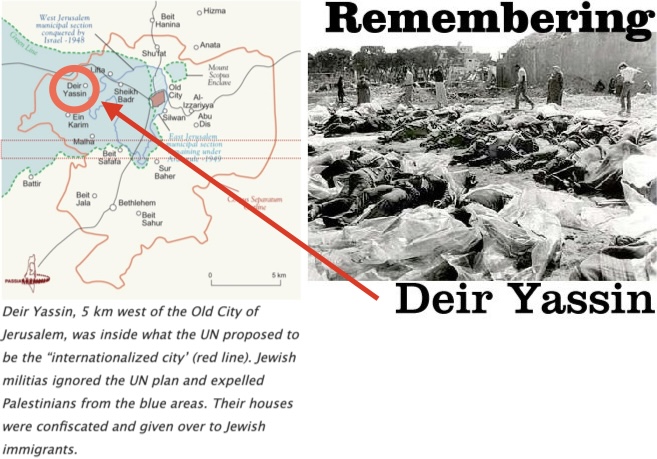

Exactly how cruel and merciless was already clear from the example of the Dir Yassin massacre. The village of Dir Yassin was located in a largely Jewish area in the vicinity of Jerusalem and, as already noted, had signed a nonaggression pact with its Jewish neighbors as early as 1942. As a result, its inhabitants had not asked the Arab Higher Committee for protection when the fighting broke out. Yet for the entire day of April 9, 1948, Irgun and LEHI soldiers carried out the slaughter in a cold and premeditated fashion. In a 1979 article dealing with the later forced evacuation of Lydda and Ramleh, New York Times reporter David Shipler cites Red Cross and British documents to the effect that the attackers “lined men, women and children up against walls and shot them,” so that Dir Yassin “remains a name of infamy in the world.” When they had finished, they looted the village and fled.

The ruthlessness of the attack on Dir Yassin shocked Jewish and world public opinion alike, drove fear and panic into the Arab population, and led to the flight of unarmed civilians from their homes all over the country.

I have jumped ahead a little. I need to backtrack to clarify a little more in the next post what the Zionist Plan D (Dalet) was all about.

Flapan, Simha. The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities. New York: Pantheon Books, 1987.

Flapan, Simha. Zionism and the Palestinians. London: Harper & Row, 1979.

Masalha, Nur. Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948. Washington, D.C: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992.

Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987. https://archive.org/details/birthofpalestini00morr/mode/2up

McDonald, James G. My Mission In Israel 1948-1951. Simon And Schuster, 1951. http://archive.org/details/mymissioninisrae002443mbp