— Peoples & Marlowe, 253

In my Origins of Religion post I focussed on anthropological evidence for the most fundamental of religious concepts that we can reasonably infer were found among our earliest homo sapiens ancestors. We saw there that the idea of a high god who is actively interested in humans, imposing on them moral codes and threatening to punish them for disobedience, was alien to our forebears just as it is generally alien to today’s hunter-gatherer societies.

So what is the evidence that informs us when and why the belief in a supreme moralizing god emerged?

The TL;DR version of this post:

| In short, the explanation offered by Peoples and Marlowe is that belief in a supreme deity that actively rewards and punishes people according to their moral conduct arises in societies that have a very large population who rely on strong cooperation in order to maintain and protect the facilities and methods on which their survival depends. These are (mostly large) societies in need of controlled complex cooperation. |

This time I rely heavily on another article by two of the authors (Peoples and Marlowe) who informed my earlier post. They ask two questions:

What circumstances could have triggered belief in a single creator, or gods that affect the lives of humans, or one all-powerful god of morality?

What characteristics of High Gods ensured that they would be culturally sustained, and why?

(255 — my formatting and bolding in all quotations)

The authors examined four types of societies across a sample of 168 in all:

Foragers

Who are the foragers? How do they live?

Foragers are the equivalent of the hunter-gatherer societies of the previous post, those among whom the idea of a moralizing high god was found to be an anomaly. (The article on which I drew for that post was published some years later than the one I am discussing now.)

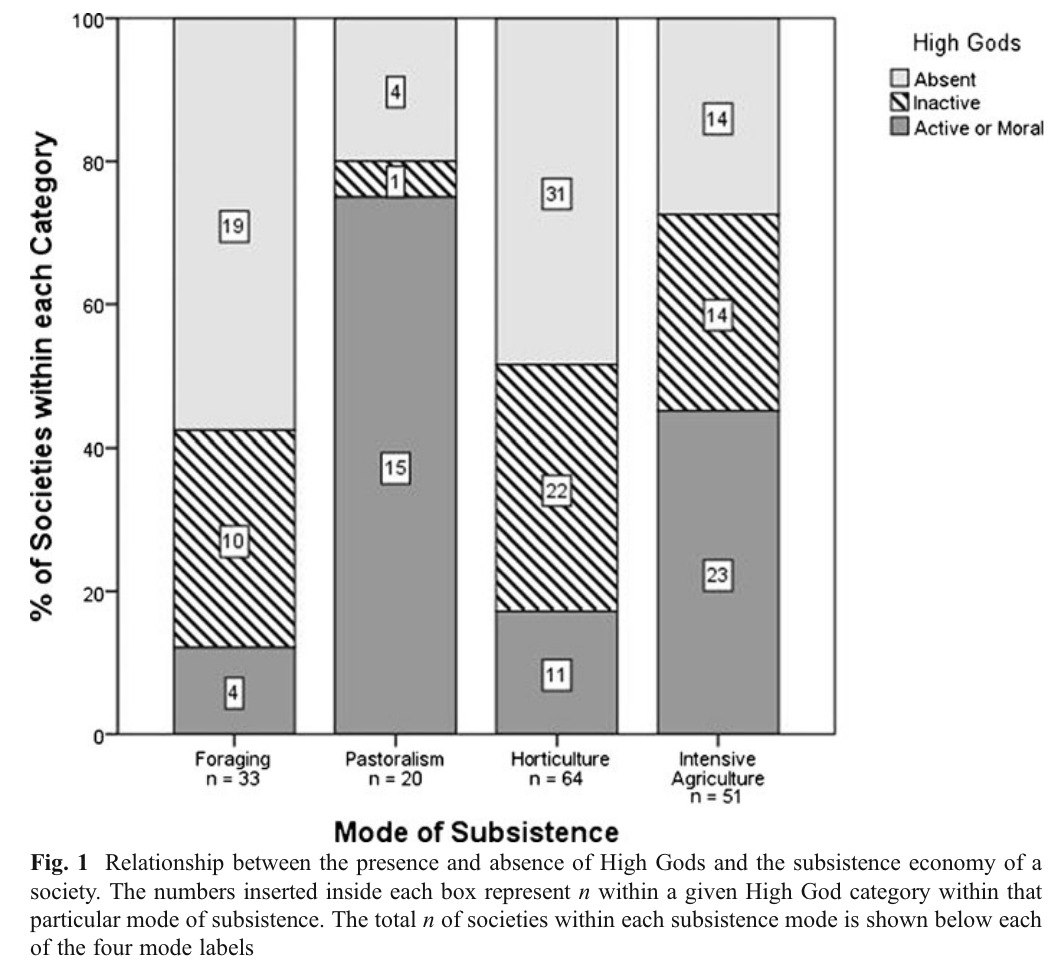

High Gods are present in all types of societies, but far less often among foragers and horticulturalists. Foragers are far more likely to have inactive High Gods or no High Gods at all….

Among our sample of forager societies, 58% had no High God and 88% had either no High God or one that was inactive.

(258, 260)

The explanation given for this absence of belief:

Most foragers are self-sufficient and usually require less cooperative labor…. They are able to survive on a variety of resources and occupy a wide range of habitats…. Most foraging societies are egalitarian and by nature resistant to others dictating what they should do. They would resist the concept of a demanding High God, and thus be less susceptible to evangelism.

(263f)

Pastoralists

Who/what are pastoralists?

Pastoralists are more mobile than foragers but also more stratified. They are often on the move in small groups sparsely scattered throughout vast areas of land. Their most important and often main source of subsistence exists in the form of large, divisible amounts of energy and wealth which can be stolen: their herd animals.

(257)

And the likelihood that they will believe in an active moralizing deity?

According to the sample studied the pastoralists were highly likely to believe in a moralizing high god.

In contrast [to foragers], pastoralists are in constant and direct contact with their main source of subsistence and livelihood in a landscape filled with moment-to-moment contingencies. Situations often become quickly unstable (herds scattering) or dangerous (attacks by marauders or wild animals). Blood feuds within and among groups are not uncommon …. Pastoralists have the highest frequency of warfare across the four modes of subsistence …, which increases the need for collective action. Recurring environmental and ecological threats take on enhanced importance because of the self-generating wealth embodied in herded animals. When drought devastates pasture, disease decimates herds, and constant violence over grazing rights becomes unrelenting, a bond of cooperation within one group or tribe must provide a survival advantage when challenged by other feuding groups.

(264)

But how might the above influence a tendency to believe in such a god?

The conceptual seed of a paternalistic High God that meddles in human morality and promises social order probably originated several times in many societies. This type of monotheistic god found fertile ground in the threatening landscape of pastoralism. A broader contextual view, based on Whiting’s theory of psychocultural evolution (Worthman 2010), might suggest that belief in a High God is the projection of the pastoralists’ sense of insecurity in the face of unmitigated ecological threat.

(265)

Horticulturalists

Horticulturalists often combine cultivation with some foraging. They are close to foragers on the productivity-subsistence continuum but less mobile and less autonomous with respect to acquiring food. We might expect to see a pattern of High Gods among horticulturalists similar to that of foragers. But increased food production leads to larger villages and related social problems (crime, disease) that reduced mobility exacerbates. The beginnings of stratification appear among horticulturalists (and complex foragers) in the form of charismatic, entrepreneurial community leaders (“big men”) who begin to establish conventions that institutionalize social controls (Johnson and Earle 2000). These leaders would gain personal power, prestige, and enhanced reproductive success from their association with active High Gods who lend support to their initiatives. Even if they were not the originators of the concept of a High God they would likely have been promoters of it.

(256)

That was the prediction. What were the findings?

High Gods are present in all types of societies, but far less often among foragers and horticulturalists.

(258)

Agriculturalists

Agriculturalists reside at the far end of the continuum, excelling in production of resources while being sedentary. Emergence of early agricultural societies benefited from the efficiency and success of cooperative labor. The demands of public works such as construction of communal storage facilities, defensive perimeters, and irrigation networks overcame limits to growth and made possible the population booms that led to big city problems…. It is now clear that agriculture began in a range of habitats from dry to wet. But the high productivity of a managed irrigation system was fundamental to the formation of pristine states in the Mexican highlands, coastal Peru, Egypt, the Indus Valley, Middle East, and possibly China…. These societies were highly stratified and their leaders would gain the most from moral conventions that reduce chances of fissioning and also ensure high levels of cooperation. But the population as a whole would eventually benefit as the society expands at the expense of other competing groups.

(256)

And the results of the survey….

High Gods were present in 73% of agricultural societies, and of those where a High God was present, 62% were active or moral.

(260)

Why?

Peoples and Marlowe note that group size increases significantly among successful agriculturalists. This leads to a higher level of social stratification or inequality:

Group size will grow with increased food production, which may depend on cooperative efforts. Drought, disease, and social-action problems constantly threaten famine. If the costs of cooperation outweigh the benefits, groups will fission as individuals leave for less-competitive resource environments. When leaving is not a good alternative, a population may remain intact even though some individuals are at a disadvantage. The result is inequality (stratification) and exploitation of others by certain individuals or kin groups (Boone 1992).

(264)

Maintaining workable cooperation among ever larger populations presents new challenges for the successful functioning of the entire society — with its need to maintain storage facilities, defences against marauders, and increasing numbers of the community wanting to go their own way. The chances of an authority figure emerging in such a situation are high.

One scenario for achieving the levels of cooperation and prosociality needed to stabilize larger populations (or growing ones) suggests the emergence of an authority figure and the concept of an overpowering high god to leverage his authority would be appealing, Peoples and Marlowe suggest.

Proposed Explanation for Belief in a Supreme Moralizing God

We propose that belief in active or moral High Gods stemmed from challenges encountered by individuals employing modes of subsistence that demanded the effective manipulation and cooperation of others in order to produce, manage, and defend vital resources. Constant threats to subsistence and survival engendered, for pastoralists and some agriculturalists, the practical idea of promoting belief in a powerful spiritual force that could promise deliverance from the enemy, and punish those who did not follow the rules of cooperation and moral constraint. The coercive power of religion was used to facilitate cooperation for the benefit of higher-status individuals, which in turn benefitted the whole group. The success of this strategy was copied, and it led to the transformation of human societies into higher levels of collective, economic organization that sustained larger populations….

This research has shown the importance of High Gods to achieving cooperation in growing populations or those under environmental stress.

(265)

Peoples, Hervey C., and Frank W. Marlowe. “Subsistence and the Evolution of Religion.” Human Nature : An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective 23, no. 3 (September 2012): 253–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-012-9148-6.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Re “What could have prompted individuals of our highly successful species to obey an unseen being who told them what they should and should not do?”

I know, I know! Because of the power it provides elites over the much more numerous non-elites. Think about it. Only some clever manipulators would come up with such a scheme, and the goal was to control people by means they could not pull off by themselves.

The monotheistic god seems clearly modeled on the tyrants that ruled ancient societies: prostration, averting eyes, even the concept of the holy, which Harold Bloom made a big deal about in The Book of J, seems modeled on the concept of the Royal. Yahweh was created in Pharoah’s image.

Dear Neil, it seems like about ten years since I last commented at Vridar. This analysis of the origin of belief suggests an economic basis for ideology. Looking at some Old Testament texts against this context, it appears that the onset of the Iron Age and the collapse of the Bronze Age from around 1200 BC created a need for hierarchical patriarchal monotheism as a requirement of military security. The ability of organised agriculture to fund castes of soldiers and priests generated the evolution of monotheism, turbocharged by the emergence of iron as the basis of imperial power.

The need to unify on larger scale to resist organised military conquest requires a belief system amenable to such a form of social arrangement. Hence the second set of ten commandments in Exodus 34:13 opens with the instruction to cut down the Asherah poles, break down the altars and smash the sacred stones and of those who live in the promised land, all as a matter of respect for the Lord, whose name is Jealous. This call to destroy earlier polytheist practices reflected that these previous religious lacked the capacity of a single supreme moralizing God to provide the social cohesion needed in a world of large-scale organised warfare.

Similar issues come up in the Book of Judges, demonstrating the challenges and consequences of small, isolated communities acting independently in a context where unity and collective belief in God were perceived as crucial for the nation’s well-being. Judges 21:25 states, “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did as they saw fit.” This verse highlights the fragmented and autonomous nature of the tribes and communities. Cohesive worship and obedience to God were seen as central to military security.

God as interpreted through priestcraft therefore served as a vital support for military leadership, providing the moral authority needed to enforce social unity.

Hi again Robert. Glad you are still around. Like you, I am keeping a watchful eye out for relevance of these anthropological finds to the origins of both Judaism and Christianity. I hope to post more about the anthropology in coming weeks. One detail, though, from my reading it was the Bronze Age that witnessed the most tyrannical of kings, sometimes presenting themselves as divine and not averse to human sacrifice to keep the fear factor alive. The first of these divine kings in our records was Naram-Sin of the Akkadian empire, 2254-2218 BCE. But you are right, I believe, in associating the Iron Age with the emergence of the “doctrinal religions” — the ones we associate with Judaism, Buddhism etc. I like your observation that the narratives reflect the need for greater social cooperation at this time.