Does a person who has a past history of depression (or any other “psychological issue”) and accordingly takes up a study of psychology inevitably become a bad psychologist?

Can a person who as a youth was involved in criminal acts ever in later years be qualified to be a social worker and role model for other youth?

Can a person who once belonged to a religious cult ever be qualified to help other cult members recover from their experiences?

Can a person who was once a fundamentalist ever be qualified to study religion and the Bible objectively and honestly?

Is it possible for a person who was once a theist and is now an atheist to have a genuine, scholarly understanding of the nature of belief in God? Or for an ex-Christian to be honest and fair about Christianity?

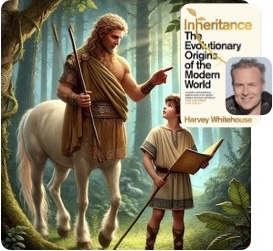

We know the answers to those questions, at least in theory. So I was intrigued to come across the following passage in the new book by the anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse.

The positive role of rituals in human history has taken me a long time to appreciate, in part because I have had a difficult relationship with rituals personally.

This is not so unusual – many of my fellow academics study the things they find particularly difficult to master or understand.

- Political scientists often strike me as poor strategists in departmental politics,

- anthropologists struggle with the nuances of their own native groups,

- and geographers are often the colleagues most in need of directions around campus.

Although my job is to study rituals, I find them rather aversive – particularly the routinized kind we were all obliged to participate in at school in the form of assemblies and chapel services. These activities seemed at the time to be not only pointless and dull but sometimes even menacingly oppressive and authoritarian. I am not alone in thinking this way, of course. As we will see in the final part of this book, many societies are shedding their ritual traditions at a rapid pace, not only through secularization but by dismissing as irrelevant or oppressive many long-established rituals associated with schooling, professional guilds, the institutions of government, and everyday domestic life. However, the more I have learned about the effects of participation in frequent collective rituals, the more I have come to appreciate their importance in fostering large-scale cohesion, cooperation, and future-mindedness. I have argued that ritual routinization helped the first farmers to settle down and create larger and larger cultural groups. But this was only the beginning of a much more complex process. . . .

Whitehouse, Harvey. Inheritance (p. 134). Cornerstone. Kindle Edition. – my formatting

Ditto!

And that is why this blog — despite my mixed background in religious experiences and current atheism — is not an “anti-Christian” blog. My interest is in understanding and learning from the latest research. My posts about the Bible are not efforts to “debunk” the Bible. It is about understanding its origins and accounting for its influence. The same for the question that seems to rile many people more than others: Did Jesus exist? That question has no interest for me. My interest is in understanding the origin and nature of the idea of Jesus in the history of religion. My interest is in applying the methods of professional research into all these questions — historical, psychological, anthropological.

Think of personal relevance. It is only natural and right and even beneficial if we take up studies in areas where our personal experiences and challenges have led us. The desire is to understand, overcome, and help others navigate similar circumstances and ideas.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Of course, this doesn’t have to mean we don’t create new rituals. One thing I’ve learned while learning about early Christianity (and we here all know it can get you to all kinds of other topics), Victorian sewing and random excursions on Wikipedia is that a lot of traditions, including rituals, aren’t nearly as old as we think they are. People just start them all the time.

‘Traditional’ clothing in many European countries is obviously ‘only’ a century or two old when you start learning what was worn when. Out-of-the-way towns were always the last to adopt the latest fashions (I’ve heard it could take decades in the past!), and it looks to me what happened to gain ‘traditional’ status is just what the far-removed people were wearing when we started appreciating that kind of dress. I wonder if it’s the German Romanticism period or the English one or???

North-West Europe is also slowly embracing Halloween as a holiday, but as a wholly secular event and aside from pumpkins it focuses more on local autumnal sights/associations. Similarly I’ve seen Easter decorations in shops be joined by more and more generic spring-like stuff, which unintentionally might match even older spring celebrations. The Netherlands is also one of the Germanic countries with a tradition of Easter branches/trees, although not every household bothers. What goes in the branch or ‘tree’ (or from what kind of tree!) is clearly more about personal tastes and fashion than tradition, but it’s a tradition nonetheless.

Theatre is one area where it’s obvious there’s always a push and pull between tradition and innovation, even when they’re not being transparent about it. Food customs is another. Almost everything we eat today was not around even 300 years ago, or in a (very) different form. Or what about the modern Western idea that weddings need to be all white, which trailed down the economic ranks until it permeated our society, and is still influencing other areas of the world as it is also disappearing again?

So I don’t think we’re wrong for shaking off traditions that were from a time with different needs or inventions. Especially ones that presume lifestyles or social structures that have changed so drastically. People are good enough at coming up with excuses for a party, or food, and all we usually need is a good enough story about how something is traditional/healthy/fun/good/whatever to start doing it. I think the wedding example also shows it sometimes simply takes time (and peer pressure) for things to become so overwhelmingly normal or popular it looks like we’ve always done things that way.

To the reason you actually posted this Neil, absolutely agree. I’m not looking into this stuff out of malice, but simply because it’s fascinating to know the weird and sometimes dirty and sometimes surprisingly normal underbelly of this religion I was thrown in from birth, and that keeps influencing me and my environment whether I know or like it or not. It’s also easier to think of things to investigate when it’s stuff you don’t entirely like, understand or agree with. I could nitpick religions or supernatural beliefs all day, but don’t ask me for a terribly critical look at, say, the game Heaven’s Vault; but I’ll look into these entirely foreign Siberian folktales and culture for funsies.

You might be interested in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger’s Invention of Tradition: they show, as one example, how the “traditions” we associate with a long-past Scotland history — the kilts, the bagpipes, even the stories …. — were all modern inventions. They succeeded despite more knowledgeable persons attempting to expose them as modern. People believe what they want to believe, and what we want usually has some reward, such as a renewed sense of identity.

As you point out, new “traditions” arise all the time. Even at a family level, I suspect many family traditions are invented as part of their ritual life through the years. Anniversaries of where couples met are remembered and celebrated by some of us. They are all part of the ways we bond together — so I have been learning from my reading. There was once a time I tried to shun all rituals and traditions from my life but one has to accept some just to function in society. And I also have come to accept that they do have a positive value. I now wish I was more comfortable with the tradition of keeping Christmas family get togethers, for example.

I should add — not only do they function as identity markers but more important, they are a way of bonding.

My pet peeve is rituals for ritual’s sake. If they’re not fun, don’t help people bond, make us feel bad, aren’t pretty, don’t teach sympathy, are terribly expensive or time-consuming, in short when the resources put into them aren’t worth what we get out of it, what’s the point? Our ancestors in general did not have the time, money or energy to do things pointlessly, so how are we honouring them by wasting our time with senseless boredom or misery? Talk about silly boasts.

An interesting point — and I am coming fresh from a little reading of the anthropological research so forgive me here — is that research shows humans have a strong proclivity to imitate behaviours that are pointless far more exactly than they imitate behaviours which have a utilitarian purpose. But yes, if the rituals do not serve their function of bonding or identity markers they will surely fall by the wayside.

Thanks for the recommendation, that does sound interesting.

I had a therapist rail against the winter holiday family get togethers, actually. The biggest problem always seems to be personality clashes. Maybe theres too little ritual (when everyone knows what to do and say, there’s less time for Opinions and Judgement), too much idealism making people feel like everything and everyone has to be perfect and the whole event just takes too long.