Having posted here often enough about my explorations into religion it is about time I investigated what atheism is all about. So many thanks to the University of Chicago Press for allowing me access to a review copy of Varieties of Atheism : Connecting Religion and its Critics compiled and edited by David Newheiser.

Having posted here often enough about my explorations into religion it is about time I investigated what atheism is all about. So many thanks to the University of Chicago Press for allowing me access to a review copy of Varieties of Atheism : Connecting Religion and its Critics compiled and edited by David Newheiser.

David Newheiser [DN] hails from a somewhat similar religious background as I do so it is interesting to compare notes. He offers his collection of essays from various authors as potentially opening “new possibilities for conversation between those who are religious and those who are not”. Maybe. You’ll have to make up your own mind about that likelihood and I return to the question at the end of this post. But for DN atheism is not simply a matter of “belief” (or “absence of belief”):

on the contrary, atheism incorporates ethical disciplines, cultural practices, and affective states. (p. 2)

DN begins his discussion with reference to the four famous horsemen of the New Atheist movement of not so very long ago: Sam Harris (The End of Faith), Christopher Hitchens (God Is Not Great), Daniel Dennett (Breaking the Spell), Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion). Recall those bus ads? “Just be good for goodness sake”?

What DN points out is that such New Atheists not only had a narrow-minded view of religion but that even

their conception of atheism is similarly impoverished. (p. 3)

So DN sweeps us up for a quick birds-eye view of past atheist authors — Bertrand Russell (“Why I Am Not a Christian”), Anthony Flew (God and Philosophy), Richard Swinburne (The Existence of God), Alvin Plantinga (Warranted Christian Belief) — before bringing us down to land in the pre-modern era of Europe. The Greek term (a-theist) came to be applied (in the sixteenth century) by Roman Catholic and Protestant apologists as they hurled the word at their opponents whom they deemed immoral.

One did not identify oneself as an atheist. One accused one’s enemies of being atheist. Until, the time of the Enlightenment:

One did not identify oneself as an atheist. One accused one’s enemies of being atheist. Until, the time of the Enlightenment:

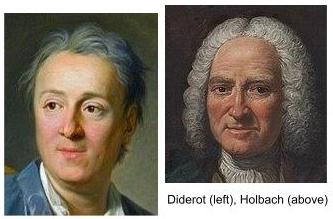

Philosophers such as Denis Diderot and Paul-Henri d’Holbach were among the first to call themselves atheists, and a century later the practice was suddenly widespread. . . . It is only in the modern period that atheism and religion came to be equated with propositional belief . . . (p. 6)

Interestingly, atheism as an identity is linked with historical shifts in what we understand by the terms “science” and “religion”:

Medieval Christians understood scientia as an intellectual habit and religio as a moral habit. On this understanding there could be no contradiction between religio and scientia, for they are not the same sort of thing. In the modern period, however, both science and religion came to be seen as bodies of objective knowledge that make propositional statements which are sometimes at odds. . . Through the objectifying tendency of the time, religion and science were made to signify the opposite of what they once meant, and in the process a new attitude became possible — the rejection of religion on scientific grounds. These shifts in intellectual culture contributed to the development of atheism as an identity, but they are not enough to explain it. (p. 7)

So what might explain it? DN draws upon Alec Ryrie’s study in Unbelievers: an Emotional History of Doubt and his account of the “seventeenth-century crisis of faith” . . . .

So what might explain it? DN draws upon Alec Ryrie’s study in Unbelievers: an Emotional History of Doubt and his account of the “seventeenth-century crisis of faith” . . . .

according to Ryrie the argument was motivated by morality and emotion rather than rationality alone.

Emotional angst came to a boil over the hypocrisy of the church for some; for others it was over the “erosion of doctrinal certainties”. Christians attacked Christians, but the arguments over time saw believers having it out with atheists, and it was about morality as much as propositional beliefs about the existence of a god.

So DN comes down to the nineteenth century and this imposing gentleman:

Ludwig Feuerbach, DN summarizes, claimed God to be a human idea that was used to buttress political control. His primary focus in his criticism of religion was moral.

Feuerbach is therefore an important source for later atheism, and yet his critique of religion arose from a moral sensibility that was informed by Christianity. Feuerbach was raised as a Lutheran, and he cited Luther hundreds of times — even referring to himself at one point as “Luther II.” Like Luther, Feuerbach’s outrage at the complacency of many Christians was motivated by his concern for the values they espouse.

Because Feuerbach’s atheism is driven by a passionate moral sensitivity, it cannot be reduced to the absence of belief in the existence of a God or gods. (pp. 7f – my bolding)

Yet ironically Feuerbach “explicitly disavowed the label of atheism”, insisting that his objection was only to certain forms of religion. Others with the same core motivations — though not chary about identifying as atheists — listed by DN:

- Friedrich Nietzsche,

- Karl Marx,

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton,

- Frederick Douglass,

- Percy Shelley,

- Hypatia Bonner,

- Mikhail Bakunin,

- and the Marquis de Sade.

Atheism for these figures was about more than belief, or disbelief in a god. It was about political control, alienation, ethics, human wellbeing.

DN observes that the difference between modern atheism and the atheism of ancient eras is that today atheism has become “an identity people claim from themselves” instead of an accusation to be spat at enemies. But the one constant is that

atheism concerns motivations that run deeper than reason.

At the outset of this post I referred to DN’s hope that his book would open “new possibilities for conversation between those who are religious and those who are not”. We can begin to see the reasoning behind that hope.

I have sought to show that atheism is . . . a polyphonic assemblage that develops in conversation with religious traditions. Despite its association with the cool light of reason, atheism is motivated by curiosity, defiance, delight, anxiety, anger, skepticism, and sympathy. (p. 8)

What is religion? Is it possible to arrive at a genuinely objective definition? DN refers to scholarly views that understand the modern concept of religion to have been “invented” in the seventeenth-century “alongside the novel conception of the state as secular.”

I have delayed my writing too long of late. I’d like to offer as an excuse, at least in part, that David Newheiser’s Varieties of Atheism has sent me down other rewarding book trails — see the evidence in images and links above — from where I’ve had to pull myself back to the review at hand. That would only be partly true, however. I look forward to discussing some selections from Varieties in coming posts.