In Genesis 6 we read a most cryptic detail that leaves us wondering what it is all about:

And it came to pass, when men began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born unto them, 2 That the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose. . . . 4 There were giants in the earth in those days; and also after that, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bare children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown.

5 And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. 6 And it repented the Lord that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him at his heart. 7 And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth . . .

We have been covering Russell Gmirkin’s book, Plato’s Timaeus and the Biblical Creation Accounts, but as I was poring through the background reading I found myself drawn back to the question of why the story of the flood in Genesis begins with an account of “sons of god”, or as the Hebrew also allows, “sons of gods”. Why did the Genesis author open his flood story with such a curious episode?

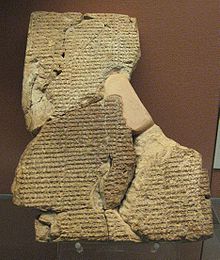

Let’s begin at the beginning — with the noncontroversial fact that Mesopotamian myth lies behind the biblical story of Noah’s flood. But let’s also examine how Mesopotamian and Biblical narratives are so very different from each other.

In Mesopotamian flood myths the gods did not use the flood to punish humankind because of its immorality or violence. No, it was not a moral judgement sent by any of the gods. It was a decision of convenience and comfort: a god was complaining of overpopulation and the resultant noise of so many people on earth keeping him awake.

The land grew extensive, the people multiplied,

The land was bellowing like a bull.

At their uproar the god became angry;

Enlil heard their noise.

He addressed the great gods,

“The noise of mankind has become oppressive to me.

Because of their uproar I am deprived of sleep. (Atrahasis myth as quoted in Hendel, 17)

Significant here is what happens after the flood. The flood marks a dividing line between two different ages:

To prevent future overpopulation, the gods take several measures: they create several categories of women who do not bear children; they create demons who snatch away babies; and . . . they institute a fixed mortality for mankind. The restored text reads: “Enki opened his mouth / and addressed Nintu, the birth-goddess, / ‘[You,] birth-goddess, creatress of destinies, / [Create death] for the peoples.'” Death, barren women, celibate women, and infant mortality are the solutions for the problem of imbalance that precipitated the flood. (Hendel 17f)

Here we find that although there were myths of great floods, the primary myth about the dividing of mythical from “historical” time was the Trojan War. And this mythical saga opened, like the Genesis flood story, with gods and mortals marrying and producing heroic figures.

In previous posts we have seen Gmirkin’s argument that the Genesis author began his flood narrative with gods marrying women under the influence of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias. What I am interested in doing here is examining the wider tradition of that same Greek myth of gods and mortals and how other accounts more directly linked this myth with the end of the primeval world. There are additional influences from this wider world of Greek myth on the Genesis author, I believe.

The Trojan War as the Divider between Mythical Time and Historical Time

Surviving Greek tales of gods living on earth with humans are compiled in a work called the Catalogue of Women. This poem begins with gods (or sons of older gods) marrying mortal women and producing heroic figures.

The Catalogue . . . does not begin with an account of the flood but with a remark about the union of the gods with mortal women to produce the heroes who are the subject of the Catalogue. This strongly suggests that the [biblical author] has combined this western genealogical tradition and the tradition of the heroes with the eastern tradition of the flood story. (Van Seters, 177)

In this myth the chief god, Zeus, decided to put an end to the mixing of divine and mortal races by means of war: he manoeuvred events to bring about the Trojan War that was meant to kill off the semi-divine heroes. Many of these heroes were taken to the Fields of the Blessed but the point of their demise was to re-establish a clear division between gods and humans. (There is no general moral condemnation of these heroes in Greek myth, nor, as Gmirkin stresses in his own work, is there moral condemnation against these figures in the biblical narrative.) From the time of the Trojan War the “age of myths” basically comes to an end and “real history” begins.

Returning to the question of why Genesis 6:1-4 is such a brief account (so brief the author must have assumed his readers knew the larger story), it is interesting to learn that brief synopses of longer tales are also found in Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women. This work, too, often reads much like a compendium of mere outlines of myths.

As in the Theogony, the genealogies were interspersed with many narrative episodes and annotations of greater or less extent. We can see that these narratives were often very summary; but they are there, and are an essential ingredient in the poem. A large number of the traditional myths, perhaps the greater part of those familiar to the Greeks of the classical age, were at least touched on and set in their place in the genealogical framework. Thus the poem became something approaching a compendious account of the whole story of the nation from the earliest times to the time of the Trojan War or the generation after it. We shall see when we come to study its contents more closely that its poet had a clearly defined and individual view of the heroic period as a kind of Golden Age in which the human race lived in different conditions from the present and which Zeus terminated as a matter of policy. We shall also see that he organized his material with some skill so as to convey his sense of the unity of the period in spite of the multiplicity of genealogical ramifications. (West, 3)

The first readers or audiences were expected to know the details of what could be abridged so they could maintain their focus on the larger plot.

In Greek myth, the intermarriage of gods and mortals was the opening scene of the tale that led Zeus to destroy the race of heroic demi-gods and so restore a new world with a clear division between the divine and human. These myths were anything but consistent, however, and other accounts offered a different reason for Zeus deciding to depopulate the earth through the Trojan War. One other reason was that the earth was simply becoming overpopulated. It is possible that the Greeks borrowed this idea from the Mesopotamian myth (see above where a god complains about the noise so many people were making) but it is also possible — since there is a comparable Indian myth — that the concept had a more general Indo-European origin (Hendel, 20).

So we have different motives for Zeus’s decision to destroy the old world and bring about a new one:

| Catalogue of Women | Cypria | Plato’s Critias |

| Zeus was hastening to make an utter end of the race of mortal men, declaring that he would destroy the lives of the demi-gods, that the children of the gods should not mate with wretched mortals. | There was a time when the countless tribes of men, though wide-dispersed, oppressed the surface of the deep-bosomed earth, and Zeus saw it and had pity and in his wise heart resolved to relieve the all-nurturing earth of men by causing the great struggle of the [Trojan] war, that the load of death might empty the world. And so the heroes were slain in Troy, and the plan of Zeus came to pass. | Zeus, god of gods, who reigns by law, did have the eyes to see such things. He recognized the degenerate state of their fair line and wished to punish them. |

The author of Genesis has taken this myth of unions between divine and human beings and applied it as the opening setting for the (Mesopotamian) flood myth, but then has — as Gmirkin argues — used Plato’s account to explain the god’s motive for destroying humanity. He has also, even more obviously, used the same idea as we read in Plato that the turning point between myth and “history” was not the Trojan War but a great flood.

Incidentally, according to the anthropologist Mary Douglas, the biblical author had a particular concern for “purity laws” that required a distinct separation of categories that had been established at creation. The mingling of sons of gods with daughters of men — though producing heroes who were not in themselves immoral — would have been contrary to the originally intended order of the cosmos and this consciousness may have further persuaded the author to open his flood narrative with this summary of the myth (Hendel, 23; Douglas, 42-58).

Genesis Replaces the Trojan War with the Flood

The author of Genesis has used the same starting event or scenario as found in the Greek myth — the age of gods and mortals marrying and producing mighty heroes of renown — and used it as the opening scene of his flood story. The Greeks had used that same myth as the precursor to the Trojan War.

In Gen 6:1-4 the [biblical author] has transformed the old myth according to his plan for the Genesis Primeval Cycle. The myth has been detached from the flood narrative, though it still precedes it, and a new motive for the flood has been supplied. The motive for the flood in Gen 6:5-8 is the increase of mankind’s evil on the earth, not the increase of population, nor the mixing of gods and mortals. That the [biblical author] is conscious of these older traditions is evident in the parallel wording of Gen 6:1, “When mankind began to multiply on the face of the earth,” and Gen 6:5, “for the evil of mankind multiplied on the earth.” The parallel wording creates a thematic counterpoint between the myth of Gen 6:1-4 and the motive for the flood. The effect of the counterpoint, I suggest, is to highlight the new motive for the flood-the evil of mankind . . . (Hendel 23f)

The Genesis flood and the Trojan War served the same function of dividing mythical or primeval time from ‘historical’ time.

Greek mythology generally falls silent after the Trojan War. The war itself is the richest of Greek myths, and its heroes have extensive traditions, but this rich texture does not outlast their sons. . . . [T]heir descendants are shadowy figures. . . . [T]he Trojan War becomes a catastrophe which serves as a boundary between the heroes and later, weaker generations, or between mythical and truly historical time. (Scodel, 35f)

And to underscore the point that they did not all die because of wickedness:

All are destroyed in the epic wars, but while some are truly dead, others live happily ever after in the Isles of the Blest. (Scodel, 37)

But note the significance of this epoch — the time when gods and mortals married — in Greek myth:

Though it is not clear from the [manuscript] remains [of the Catalogue or Women] whether it is the gods themselves who are to live apart from men in the future, or their children, who would on this understanding be removed to the Isles of the Blest, evidently in this poem Zeus began the war with the intention of eliminating the demigods from mortal life and enforcing a stronger separation between gods and men. By implication, once the demigods have been removed, no others will be engendered; this makes the war the natural conclusion of the poem, whose subject has been the unions of mortal women with divinities which created the [demi-gods]. (Scodel, 37f)

Hesiod’s myth was about the rise of the demi-gods from the unions of gods (and divine sons of other gods) mating with mortal women and producing a race of heroic demi-gods and how and why that world of myth and heroes came to an end and “real history” began.

The Trojan War thus functions as a myth of destruction, in which Zeus brings about the catastrophe in order to remove the demigods from the world and separate men from gods, to relieve the earth of the burden caused by overpopulation, or to punish impiety. It has been noticed that these motives are found in the extant Near Eastern flood myths, though the subject has yet to receive a full discussion. In Near Eastern myth the Deluge has a function like that of the Trojan War in Greek, serving to divide the present age and its world order from an earlier, and in some ways preferable time. The Babylonian epic of Atra-hasis gives a motive for the Deluge which is very similar to Zeus’s motive for beginning the Trojan War in the Cypria, for the gods are distressed by the noise created by human beings when mankind multiplies. . . (Scodel, 40)

In the words of another,

[A]lthough the Trojan War is a military encounter rather than a flood, it functions in a way similar to the Babylonian deluge: it serves as the great destruction which divides the prior age from the present age, just as does the flood in the [Mesopotamian] myth and in other Mesopotamian traditions. . . . [J]ust as the Trojan War becomes the first datable event in Greek history, the flood becomes the first datable event in much ancient Near Eastern tradition (e.g., Berossos’s Babyloniaca) (Hendel, 18)

Zeus brings on the Trojan War to destroy the heroic demigods, so that the proper division of realms between gods and humans might be secured. (Hendel 19)

The Trojan War functions in a manner similar to the Semitic flood tradition. (Hendel 20)

Freedom to Re-write the Myth

So why would the biblical author, having begun with the same heroic age scenario as the Greek myth, have linked this mythical time with the flood?

At this point we have to take note that Greek myths were diverse and inconsistent — depending on who was documenting them, when and where and why.

The Greek traditions do not derive all of humankind from a single source or common human pair at the beginning of time. Thus there could be many different beginnings at different places, and this possibility plays havoc with the many later attempts to construct a universal history from primeval times.

The Greek tradition of origins, in fact, seems to focus more on the origins of particular states, tribes, and peoples than on humankind in general. They are in the nature of “charter myths” that legitimate custom, institutions, and territorial claims. These states and tribes it traces back to heroes and eponymous ancestors . . . (Van Seters, 79)

If you have been following the posts on Russell Gmirkin’s work you will see where that quote is leading us: the primeval history of Genesis 2-11 is the precursor to the history of Israel as the people of God, custodians of God’s laws, and in this respect it follows the genre of writing, and in modified form some of the content, that we find in the Greek world.

Plato was rewriting myths and we have been studying evidence that the biblical authors were following Plato not only in content but also in the rearrangement of material to suit their own needs — as was the literary Greek way.

Indeed, the very inconsistencies among the myths probably cried out for authors to try their hand at rewriting them in order to glorify the people and places with which they identified:

From the fifth century BCE we have our earliest Greek account of a flood myth and that addition only increased problems for anyone wanting to piece the different episodes together into a single narrative:

In the Greek tradition, the flood story is put in a rather awkward place within the time of Deucalion at the beginning of the human race before the proliferation of humankind. (Van Seters, 177)

Scholars have noted the oddity of characters (such as Deucalion) in pre-flood myths reappearing in other myths as flood heroes:

Another explanation for the end of the primeval age is through a particular disaster that few survived. The clearest example of this is the flood tradition, but its appearance in Greek tradition does not seem to be any earlier than the early fifth century B.C. and was very likely an import from the Near East.12 (Van Seters, 81).

12. The earliest reference to the flood is in Pindar, Olympia 9.49ff. Here the remark about the flood, referred to as a new song of the Muses, clearly interrupts the account of Pyrrha and Deucalion and their offspring, the heroes of the race of Iapetos (Japheth). The relationship of this earlier level, without the flood, seems particularly close to the tradition reflected in the Catalogue of Women (see below, n. 18). (Van Seters p. 99)

Note some of the variations of origins found among Greek myths:

- The population of the Peloponnesus began with “the first man” Phoroneus;

- the people of Thebes were formed when Cadmus planted the teeth of a serpent or dragon in the ground;

- the natives of Aegina from ants that Zeus turned into humans;

- and the people of central and northern Greece arose from stones that Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha threw behind them.

In some myths Deucalion and Pyrrha were the survivors of a flood and are the start of a new race of humans, but when they so appear there is no time for the age of heroes that we read of in other myths. In other words, there is no consistency among the stories and no general account of a total destruction of the entirety of humanity. The earliest myth of Deucalion limited his activity to central and northern Greece:

The form of the genealogy [of Deucalion] indicates that the epic traditions have been grafted on to a pre-existing structure, causing an extension of its geographical coverage well beyond its original limits. (West, 139)

In Genesis 2-11 we read a series of anecdotes about origins that have been drawn from various sources and woven together to create a literary whole. The same type of work has been found in Greek literature and the primeval history in Genesis 2-11 follows the same style.

The biblical narrative is therefore not unique as has been claimed. With respect to the “Table of Nations” following the Genesis flood, the similarity with Greek myth is noted here, too:

Contradicting [the] claim about the uniqueness of the Table of Nations [in Genesis 10] is the example of the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women, which was referred to above. The main body of this work contains an elaborate series of segmented genealogies consisting primarily of the eponyms of Greek-speaking peoples, nations, tribes, and geographical place names. Some foreign nations well known to the Greeks are also included. Mixed with these eponyms are the personal names of heroes and primeval kings. These have been fitted into the segmented genealogies of tribes and states, often with great ingenuity. Also included within the main body of the text are shorter or longer accounts or summaries of heroic legends. This makes it remarkably like [the Genesis] Table of Nations, which also includes the story of the hero Nimrod within its structure. . . .

And as quoted earlier,

. . . The Catalogue, on the other hand, does not begin with an account of the flood but with a remark about the union of the gods with mortal women to produce the heroes who are the subject of the Catalogue. This strongly suggests that the [biblical author] has combined this western genealogical tradition and the tradition of the heroes with the eastern tradition of the flood story. (Van Seters, 177)

The following description of Hesiod’s Catalogue of Women might be equally applied to Genesis 2-11:

The composition of the Catalogue was not the result of a gradual accumulation of materials but reflects a systematic plan with careful construction of its various parts. The framework of the introductory proem and the concluding narrative represent their own perspective of the heroic age as a period in which gods and humans lived together—an age that was brought to an end by Zeus to make a clear separation between the two realms of human and divine. Into this framework, and somewhat at variance with it, the genealogies and narratives are placed. Among these one can distinguish a number of major independent epic cycles that involved a different set of heroes and were associated with different regions. The author has collected these traditions, reshaped them to suit his pattern, and added a number of bridging blocks to fill in the gaps. The result did not eliminate all the inconsistencies, and later genealogists did much in their works to integrate the various major traditions.

The Catalogue was perhaps the original archaiologia and the basis for all later attempts at primeval history. This antiquarian tradition became a major preoccupation of many historians from the sixth century B.C. onward as a subject of vital concern to most of the states and communities of the Greco-Roman world. (Van Seters, 90)

We can see inconsistencies in the biblical account that may have resulted from the same process that Hesiod used in trying to put together a coherent storyline from various contradictory sources. One example is the documentation of the invention of various arts and crafts among the descendants of Cain. What was the point of that list if all their descendants were wiped out in the flood?

Another inconsistency that points to complex source material is that a few of the “nephilim” (“giants”/semi-divine heroes) were later found to still be on earth — after the flood was presumed to have destroyed them all.

There exists a contradiction in the traditions of the Nephilim. According to Gen 6:4 the Nephilim “were on the earth in those days,” prior to the flood, and thus ought to have been destroyed by the flood. Yet according to other traditions they are found in the land of Canaan by the early Israelites and are wiped out under the leadership of a great hero of Israel, either Moses, Joshua, Caleb, or David. (Hendel, 21)

Gmirkin has likewise pointed to evidence of different sources behind the Genesis flood:

A similar plot line appears in the flood story of Gen 6:14-9:2. This story was not taken from Critias. . . .

Instead, Gen 6:14-8:19 for the most part reverted to its Mesopotamian source material, namely that found in the Babyloniaca of Berossus. (Gmirkin, 227)

What I find of interest is that by the Hellenistic period Greeks were adapting and merging different mythical traditions to create unique pre-histories of local populations, city-states, subgroups with different political systems and favoured gods. That looks like the kind of literary environment in which authors would be encouraged to produce a new account of another people that had come under the rule of the Greeks, something like the stories we read in the primeval history of Genesis.

Yes, it is very likely that those responsible for Genesis were heavily influenced by Plato, but one might also suggest that they were equally aware of other adaptations of those myths in the various Greek sources, as well as the Babylonian myths through the Hellenistic author Berossus.

Perhaps above all, one sees in the various scholarly sources I have cited in this post that the idea that an author of Genesis should be influenced by Greek sources is not out of bounds. With Gmirkin, however, the focus is on the late third-century date for those Greek-influenced works.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Routledge, 2013.

Gmirkin, Russell E. Plato’s Timaeus and the Biblical Creation Accounts: Cosmic Monotheism and Terrestrial Polytheism in the Primordial History. Abingdon, Oxon New York, NY: Routledge, 2022.

Hendel, Ronald S. “Of Demigods and the Deluge: Toward an Interpretation of Genesis 6:1-4.” Journal of Biblical Literature 106, no. 1 (March 1987): 13. https://doi.org/10.2307/3260551.

Scodel, Ruth. “The Achaean Wall and the Myth of Destruction.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 86 (1982): 33. https://doi.org/10.2307/311182.

Van Seters, John. Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis. Louisville, Ken.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1992.

West, M. L. The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women: Its Nature, Structure, and Origins. Oxford Oxfordshire : New York: OUP Oxford, 1985.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This is fascinating. I suspect there is no simple genealogy of these books – there was probably a cross-fertilization between cultures over centuries. Marku Vinzent, I think in his book on Marcion, has proposed a similar web of influence for the New Testament.