(continuing the series on Russell Gmirkin’s Plato’s Timaeus and the Biblical Creation Accounts) ….

If the authors of Genesis were inspired by Plato’s discourse on the origins of the cosmos in Timaeus how can one explain the obvious contrast between Plato’s lengthy scientific and philosophical reasoning and the simple narrative in Genesis 1:1-2:3?

To answer this question Russell Gmirkin [RG] begins by explaining that there were “seven distinct modes of Greek discourse on cosmogony” and that authors adapted their rhetoric according to the particular audiences each had in view.

1. Scientific Discourse: Natural philosophers most often wrote for their elite, wealthy and educated peers. “Schools” or “universities” were established by prominent thinkers (e.g. Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum) and cosmogonies were written to expound their underlying philosophical reasoning.

2. Revealed Myth: Parmenides of Elea wrote cosmogonies addressed to two different audiences. In Way of Truth he wrote a detailed scientific discourse for his educated peers. In Way of Opinion he wrote a cosmogony in the form of a myth that was being taught by the goddess Justice or Necessity.

In this mode of discourse, the aim was not to achieve knowledge but to induce belief in the theories being presented. Here Parmenides appears to have anticipated Plato, who advocated implanting beliefs in the citizenry as a necessary precursor to achieving true knowledge in a select few . . . . It appears that Parmenides (like Plato) saw a social utility in presenting theories of cosmogony to the general public under divine authority, since he named the appropriate goddess as Necessity or Justice, “who steers the course of all things,” suggesting that a mythical account on cosmogony that recognized a divine steering principle was needed to ensure a pious and just citizenry. It appears that the populace was induced to believe not only that this account of the origins of the universe was divine, but also had the endorsement of the scientific educated elites. The poetic form of the discourse may have been intended to enhance its appeal to the masses. (pp. 66f)

3. Myth as Discourse (Enchantment): Plato taught that in an ideal government philosophers should rule and oversee all aspects of education from infancy to adulthood. The curriculum for the young had to consist of myths that fostered “good” behaviour. These myths needed to be attractive to all ages, especially the young, and hence were to be relayed in songs, poems, theatrical performances and public readings at festivals. Existing myths that told of gods were useful but first had to be censored by the philosopher rulers to remove from them every negative and immoral act of the gods. Nothing bad about the gods was to enter the minds of the citizens. Education was to encompass the whole society, from mothers telling infants nursery rhymes to entertaining performances (singing, reading, acting) for the young and adults.

The aim and intended reception of discourse by myth was to induce belief, and thereby implement societal conformity to theological and ethical norms. Myth, whether in the form of song, story or theatrical performance, was chosen as the medium for inducing belief, due to the pleasant, entertaining, enchanting character of the myth . . . Myth was thus the chosen rhetorical tool to condition the emotions and convey theological and ethical truths on a pre-rational level to intellectually unsophisticated audiences. (p. 68)

Genesis 1 reads as an authoritative story. It was not entirely a myth like other creation myths. It presented a scientific account of the moving power over the primordial chaos bringing about a series of separations that led to day and night, earth and sea, the spontaneous generation of life forms from the ocean, and so forth.

A story format was highly suitable for instilling beliefs about God’s fashioning of the universe for audiences of all ages and was easily understood by school children and even the youngest children, important target audiences under Plato’s system of education. (p. 68)

The second creation account (Genesis 2:4ff) follows up the cosmogony with a mythical narrative about the origins of animals and humans, the reason humans dominate the animals, the introduction of sexual reproduction and clothing, etc. It is a story easily understood by all, from the very young to the old. The beginning of the account may be a subtle reminder of Greek myths:

These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created . . . — see Gen 2:4 for the Hebrew text

Heaven (Ouranos) and Earth (Ge) also appeared as the earliest gods in the théogonies of both Hesiod (Theogony 116-27, after Chaos) and Plato (Timaeus 40e) (p. 68)

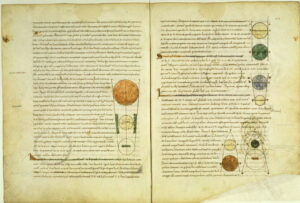

4. Education (Belief): For more formal education in the home and school settings Plato permitted the teaching of astronomy but with a caveat. Some natural philosophers taught that the sun, moon and stars were inanimate bodies of rock or fire and moved according to physical processes. Plato saw those teachings as a threat to morality because they were the first step on the slippery slope towards atheism. The general population needed to be taught that these heavenly bodies were divine and moved as divinities would — in perfect circles. The sphere was the perfect shape befitting a deity because it could move while remaining in the same place. The detailed philosophical reasoning behind this astronomical knowledge would only be taught to those able to attend higher education. For most people all that was necessary is that they be taught “the facts” without the rational arguments for them. The proposed curriculum was thus an ancient form of “creation science”. Instructors were to possess the authority that came with a reputation for high morals and deep knowledge and above all to learn to teach with persuasive eloquence.

The level of discourse found in the cosmogony of Genesis 1 corresponds closely with Plato’s curriculum of instruction on astronomy and cosmogony in a classroom setting. There is a high level of scientific content … , but without the scientific or philosophical reasoning found in university level discussions. Rather, Genesis 1 is presented for simple belief as an authoritative myth that conveys both scientific assertions about the origins of the kosmos and substantial theological content … appropriate to lower education which, in early Judaism, included both synagogue aimed at the community as a whole and biblically mandated instruction of youths in a family setting. (p. 70)

RG suggests that the inclusion of God sanctifying the sabbath day indicates that the creation story was part of teaching during sabbath observances. As for the ensuing story of the creation of Adam and Eve and their temptation by the serpent and expulsion from Eden and the requirement to labour in the fields and suffer pain in childbirth, we have an introduction of more mythical content that made the stories suitable for less sophisticated audiences.

5. Laws (Compiance): Plato’s education system required that the citizens only acknowledge gods approved by the state. Introducing “foreign gods” was to be an act of treason. Further, citizens were required to believe that

- the gods existed

- the gods cared for humanity

- the gods could not be bribed by prayers and sacrifices of the wicked

Plato considered such beliefs necessary for an orderly state of obedient and loyal citizens. We saw in an earlier post where RG discussed Plato’s Laws in depth that the preamble was a vital part of any law code. Before I read Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible I was inspired by Philippe Wajdenbaum’s Argonauts of the Desert to read Plato’s Laws with the laws given on Mount Sinai in mind. I was astonished, to put it mildly, to see just how closely Laws was a blueprint for the biblical legislation. In Bible’s Presentation of Law as a Model of Plato’s Ideal I set out some of the comparisons that included a discussion of the significance of the preamble to the laws. I later covered RG’s discussion of the preamble in his 2017 book: How Plato Inspired Moses: Creation of the Hebrew Bible.

In short, Plato stressed the importance of a story-form introduction to a law code to educate and persuade citizens of the benefits of observing the law and to impress upon them the divine authority and source of the laws. Plato’s introduction to his recommendations of laws was directed at adults who had been exposed to the atheistic teachings of natural philosophers. His preamble accordingly underscored three ideas: that the sun, moon, stars and planets were gods; that those gods were watching over them, caring for them; and that they could never be swayed by the prayers and sacrifices of the wicked.

The general populace in the regions of Jerusalem and Samaria were not likely to be exposed to Greek atheistic thinking but they were in contact with polytheistic worship.

Astronomy accordingly does not figure in Mosaic legal rhetoric, except in Deut 4:19, where the children of Israel were cautioned against observing the heavens, lest they be seduced into worshipping the celestial bodies as gods. Although this had been traditionally interpreted as polemics against Assyrian astral gods (von Rad 1961: 53-4; Westermann 1984: 127; Milgrom 2004), this appears to be based on a pre-Hellenistic dating of Deuteronomy. Deut 4:19 is more plausibly interpreted as reflecting opposition to Plato’s description of the celestial bodies as visible gods (Timaeus 40a-c, 41a; Laws 7.821b; 10.886a,d; Cratylus 397c-d). (p. 72)

6. Philosophy (Knowledge): Plato wrote that leaders needed to be educated in the higher philosophical learning that undergirded the theologically correct cosmogony. Timaeus was an example of a text for that kind of higher learning. Timaeus included what Plato described as plausible or likely mythical explanations, as well. He acknowledged, though, that future teachers might come up with their own myths or even explanations for the origin of the universe that they felt would have greater plausibility (Timaeus 29b-d, 55d). In Laws Plato set out the educational program that the ruling body (the Nocturnal Council) would apply.

Plato’s Laws was envisioned as the key text that contained the proper arguments on child-rearing, education and laws for the philosophical training of the ruling class, although further research into international practices in these areas was also encouraged. (p. 74)

7. Reform (Compliance): But what was to happen if some adults forsook what they had been taught since infancy and dabbled with atheistic notions? They were to be taken out of society and put through re-education programs. Depending on the case, they might be punished with beating, prison, fines, exile or death. But the leaders were expected to be masters of the highest education and understanding of the principles behind the “correct” cosmogony and beliefs about the gods so that they could know how best to re-educate these “lost souls”.

—o—

RG addresses each of the above seven modes of rhetoric in terms of the special requirements for each type of audience, the type of content required and manner of its presentation for maximum persuasive effect. I have tried to give the basic outline of each of these types of discourse from the Greek world.

The cosmogony in Genesis 1 does not resemble the mythical cosmogonies of the Ancient Near East, but addresses the fundamental scientific questions characteristic of Greek scientific cosmogonies. Genesis 1 has accordingly been classified here as a scientific-theological-mythical cosmogony.

Genesis 1 is not a scientific text but it does contain the type of scientific descriptions we find among the Greek natural philosophers, embedded in theological instruction. Genesis 2-3 introduces more mythical tropes to describe the origins and conditions of humans. RG thus concludes that these chapters are part of a program to shape the beliefs and character of Hebrews in the Hellenistic era.

The aim of this authoritative account was to promote simple orthodox belief in a supreme cosmic deity as benevolent creator of the kosmos among an intended audience of youths and ordinary citizens of the community. Its method for accomplishing this was to present theories on cosmogony in the form of a scientifically and theologically informed myth, a story authoritatively presented as fact. The mythical content both in Genesis 1 and in the less scientific Genesis 2-3 contributed to the ethical and theological indoctrination of the target audience which included children, for whom stories were the best mode of education. (pp. 75f)

to be continued…

Gmirkin, Russell E. Plato’s Timaeus and the Biblical Creation Accounts: Cosmic Monotheism and Terrestrial Polytheism in the Primordial History. Abingdon, Oxon New York, NY: Routledge, 2022.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Can we infer from your opening paragraphs that this argument includes, or constitutes, an argument about the order of composition?

Sorry, Clarke — can you clarify for me exactly what you mean by “order” of composition? Thanks.

I can’t talk for Clarke but it seems to me that we’re seeing an argument that: Gen2:4 and onward are older than Gen1:1-2:3, that Gen1 is post-Plato, and that the remainder of Gen harks back to a more bog-standard creation myth with monsters being slain, giants in the earth, and so forth.

So Gen1:1-2:3 has been attached to the front of a pre-existing narrative. Not a unique occurrence in the Bible.

Thank you, Neil. Excellent summary of RG’s argument. Considering the intended audience of the Torah, it’s clear why all the emphasis was on BELIEF rather than REASON.

Well, Plato is 427 BCE – 347 . But I’m pretty ignorant on the sections from Genesis. It seems like the dates are all over the map, depending on who you go to for the answer. Does this make sense? I have seen the argument Thomas Worthington refers to in the last part of his comment, but I just wondered what the foundational assertion is as to dates of composition, creation account I guess since we know Plato.

Yes, RG’s thesis is that the early chapters of Genesis were written as late as the third century bce.

He has gathered evidence to demonstrate that these chapters are indebted to Greek ideas. Not only and exclusively indebted to the Greeks, but that the Greek literature that came in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests had a strong influence on the content and style of Genesis 1-11 (and other books of the Pentateuch).

There is no independent evidence that places any of the biblical works before the third century.

Of course, this hypothesis of RG’s flies in the face of the traditional and mainstream Documentary Hypothesis that places early versions of our biblical books existed in the days of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

Some years back I posted a few of the critiques that have emerged to challenge the Documentary Hypothesis. I should collate them all and post a new “table of contents” page on the blog. Meanwhile, one can always start where many others once started, with Philip R. Davies’ In Search of Ancient Israel: http://vridar.info/bibarch/arch/index.htm