I have been inspired by the response of historian Miles Pattenden to John Dickson’s article Most Australians may doubt that Jesus existed, but historians don’t to write a second post. This time I want to address the question of historical methods more generally in contrast to my initial rejoinder where I focused on the sources Dickson himself called upon.

Miles Pattenden’s reply, On historians and the historicity of Jesus — a response to John Dickson, begins with a datum that should be obvious but seems too often to get lost in the heat of the bloodlust of argument. All the appeals to authority do is point us to the fact that most references to Jesus in historical works (even in works addressing specifically the “quest for the historical Jesus”) “accept an historical Jesus as a premise” (Pattenden). Such references can be nothing more than

evidence only of a scholarly consensus in favour of not questioning the premise. (Pattenden)

Another introductory point made by Pattenden introduces a factor that again ought to be obvious but is too often denied, that of institutional bias:

Christian faith — which, except very eccentrically, must surely include a belief that Jesus was a real person — has often been a motivating factor in individuals’ decisions to pursue a career in the sorts of academic fields under scrutiny here. In other words, belief in Jesus’s historicity has come a priori of many scholars’ historical study of him, and the argument that their acceptance of the ability to study him historically proves his historicity is mere circularity.

Where does this situation leave other scholars in other disciplines who speak of Jesus? I’m thinking of historians who write of ancient Roman history and make summary references to Christian beginnings as a detail within the larger themes they are discussing, or of educational theorists who speak of the methods of instruction by past figures like Socrates or Jesus. It would be absurd to suggest that such authors have necessarily undertaken a serious investigation into the question of Jesus’s historicity before making their comments. This question is getting closer to a key point I want to conclude with but before we get there note that Pattenden gets it spot on when he writes:

Just as significantly, the existence of a critical mass of scholars who do believe in Jesus’s historicity will almost certainly have shaped the way that all other scholars write about the subject. Unless they are strongly motivated to argue that Jesus was not real, they will not arbitrarily provoke colleagues who do believe in his historicity by denying it casually. After all, as academics, we ought to want to advance arguments that persuade our colleagues — and getting them offside by needlessly challenging a point not directly in contention will not help with that.

Miles Pattenden proceeds to touch on the nature of the evidence for Jesus compared with other historical subjects, the disputed nature of the array of sources for Jesus, the logical pitfalls such as circularity, and so forth, all of which I’ve posted about many times before.

But the historical Thakur may be as well attested by categories (if not quantity) of contemporary evidence as the historical Jesus is. So do we not risk charges of hypocrisy, even cultural double standards, if we accept different standards of proof for the existence of the one from that for the other?

Such questions ought not to be entirely comfortable for historians of liberal persuasion or those of Christian faith. However, the authors of “The Unbelieved” in fact pose their conundrum the other way around to the way I have described it — and in their position may lie a helpful way to reconcile beliefs concerning the historicity of Jesus and in the need to be sufficiently critical of sources. (Pattenden. Bolding in all quotes is my own.)

But then Pattenden veers away from the question of the historical reality of “the man Jesus” and introduces a discussion among historians about how to study and write about events that the participants attribute to divine commands and acts. This approach may seem to beg the question of Jesus’ historicity but bear with me and we will see that that is not so. I want to focus on just one point in that discussion because I think it has the potential to remove all contention between believers and nonbelievers in the study of Christian origins. The authors – Clossey, Jackson, Marriott, Redden and Vélez – propose three strategies for the handling of historical accounts in which the historical subjects testify to the role of divine agents in their actions. It is the first of these that is key, in my view:

- Adopt a humble, polite, sceptical, and open‐minded attitude towards the sources.

Notice that last word: “sources”. The historian works with sources. Sources make claims and those claims are tested against other sources. Claims made within sources are never taken at face value but are always — if the historian is doing their job — assessed in the context of where and when and by whom and for what purpose the source was created. The article goes on to say

Often miracles have impressive and intriguing documentation. A Jesuit record of crosses appearing in the skyabove Nanjing, China, mentions “numberless” witnesses who saw and heard the miracle, and later divides them by reliability into “eleven witnesses, plus many infidels” . . . .

Many biblical scholars will say that Jesus was not literally resurrected in the way the gospels describe but that the followers of Jesus came to believe that he had been resurrected. We can go one better than that: we can say that our sources, the gospels, claim that the disciples of Jesus believed in the resurrection.

Notice: we cannot declare it to be a historical fact that Jesus’ disciples believed Jesus had been resurrected. The best a historian can do is work with the sources. The sources narrate certain events. To go beyond saying that a source declares X to have happened and to say that X really happened would require us to test the claim of the source. Such a test involves not only examining other sources but also studying the origins and nature of the source we are reading. Do we know who wrote it and the function it served? When it comes to the gospels, scholars advance various hypotheses to answer those questions but they can rarely go beyond those hypotheses. It is at this point that the “humble, polite, sceptical, and open-minded attitude towards the sources” is called for. It is necessary to acknowledge the extent to which our beliefs about our sources are really hypotheses that by definition are open to question and that our long-held beliefs about them are not necessarily facts.

As long as a discussion is kept at the level of sources and avoids jumping the rails by asserting that information found in the sources has some untestable independent reality then progress, I think, can be made.

A problem that sometimes arises is when a scholar writes that, as a historian, they “dig beneath” the source to uncover the history behind its superficial narrative in a way analogous to an archaeologist digging down to uncover “history” beneath a mound of earth. The problem here is that the “history” that is found “beneath” the narrative is, very often, the result of assuming that a certain narrative was waiting to be found all along and that it was somehow transmitted over time and generations until it was written down with lots of exaggerations and variations in the form we read it in the source. In other words, the discovery of the “history behind the source” is the product of circular reasoning. It is assumed from the outset that the narrative is a record, however flawed, of past events. Maybe it is. But the proposition needs to be tested, not assumed.

It should not be impossible for atheists and believers, even Jesus historicists and Jesus mythicists, to work together on the question of Christian origins if the above principle — keeping the discussion on the sources themselves — is followed. The Christian can still privately believe in their Jesus and it will make no difference to the source-based investigation shared with nonbelievers. Faith, after all, is belief in spite of the evidence.

There is a bigger question, though. I have often said that to ask if Jesus existed is a pointless question for the historian. More significant for the researcher is the question of how Christianity was born and emerged into what it is today. The answer to the question of whether Jesus existed or not, whether we answer yes or no, can never be anything more than a hypothesis among historians. (It is different for believers but I am not intruding into their sphere.) The most interesting question is to ask how Christianity began. Even if a historical Jesus lay at its root, we need much more information if we are to understand how the religion evolved into something well beyond that one figure alone. It is at this point I conclude with the closing words of Miles Pattenden:

Partly because there is no way to satisfy these queries, professional historians of Christianity — including most of us working within the secular academy — tend to treat the question of whether Jesus existed or not as neither knowable nor particularly interesting. Rather, we focus without prejudice on other lines of investigation, such as how and when the range of characteristics and ideas attributed to him arose.

In this sense Jesus is not an outlier among similar historical figures. Other groups of historians engage in inquiries similar to those that New Testament scholars pursue, but concerning other key figures in the development of ancient religion and philosophy in Antiquity: Moses, Socrates, Zoroaster, and so on. Historians of later periods also often favour comparable approaches, because understanding, say, the emergence and diffusion of hagiographic traditions around a man like Francis of Assisi, or even a man like Martin Luther, is usually more intellectually rewarding, and more beneficial to overall comprehension of his significance, than mere reconstruction of his life or personality is.

This approach to the historical study of spiritual leaders is a more complex and nuanced position than the one Dickson presents. However, it also gives us more tools for thinking about questions of historicity in relation to those leaders and more flexibility for how we understand about their possible role (or roles) in our present lives.

Amen.

Surely no scholar would want to be suspected of secretly doing theology when they profess to do history so no doubt every believing scholar can also say, Amen. And if an evidence-based inquiry leads to scenarios beyond traditional theological narratives for the believer, or scenarios closer to traditional narratives than the nonbeliever anticipated, then surely that would inspire even greater wonder and a double Amen!

Pattenden, Miles. “Historians and the Historicity of Jesus.” Opinion. ABC Religion & Ethics. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, January 19, 2022. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/miles-pattenden-historians-and-the-historicity-of-jesus/13720952.

Clossey, Luke, Kyle Jackson, Brandon Marriott, Andrew Redden, and Karin Vélez. “The Unbelieved and Historians, Part II: Proposals and Solutions.” History Compass 15, no. 1 (2017): e12370. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12370.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This is an excellent article thanks Neil !! I am inclined to mention that (IMO) the points and issues raised here in regard to the historicity (or otherwise) of Jesus would also seem to apply to the historicity (or otherwise) of Paul.

Are you aware of Dr. Carrier’s blog-post about Paul’s historicity? Not that I disagree with your point, but I think that it may be usefully treated by Dr. Carrier.

I find Paul to be a major problem. The evidence that we have does not gell, in my mind, with any external figure remotely like the persona in the letters and career read about in Acts.

The conflicts between the stories told in the letters and the story told in Acts are a good reason for suspicion about Paul.

And Acts 21:31 to 22:25 is a bit hard to swallow. The officer arrests the man at the centre of the upheaval and then allows him to make a speech to those who were trying to kill him? Not likely.

Neil, what “evidence that we have” are you referring to? I assume that you are referring to the non-canonical texts about Paul and to Justin Martyr’s not mentioning Paul (and perhaps claims that Paul was beloved by the gnostics), but clarification would be useful for us, I think.

After I have finished uploading translations of Bruno Bauer’s criticism of the synoptic gospels I hope to turn to his study of Paul’s letters. Then I will be more focused on that subject and be better able to do justice to your question. In the meantime, the key problems I have with the current view of the origins of Paul’s letters are:

1) we have no indisputable evidence that they were known to anyone before the mid-second century;

2) despite claims to the contrary, by and large, they do address problems extant in the second century;

3) though some scholars propose that the author was often muddled and always changing his mind, it may be more realistic to think that there are multiple authors/redactors;

4) it is problematic, I think, that we have no evidence for a travelling power evangelist or multiple evangelists a la Acts before the mid-second century;

5) the evidence we do have in the early second century actually leaves no visible room for a Pauline apostle doing his thing;

6) the account of Paul in Acts draws for its content on revisions of Jesus and Peter stories (with some guidance from the epistles — but see point #1) and contains no indication of being derived from sources about the life of a third character, a Paul himself — the “we passages” notwithstanding’

7) the letters are not real letters despite what a number of scholars attempt to argue;

8) the letters are arguably compositions that conform well to the tradition of “pious fictions” in the history of Jewish theological discourses.

Neil, I thought that you might find the following thoughts by me to be worthy of addressing in your readings and/or writings:

“I have no problem with dating the “Authentic” Pauline letters to the 1st century CE and the Pastoral epistles (1st and 2nd Timothy, Titus) to the 2nd century CE, because, among other things, the pastoral epistles describe a better developed community with distinct ranks, scriptures, and theological controversies with other Christian groups (if I understand correctly). The Pastoral epistles also allude in 1 place to a story from the gospels. When were the Pastoral epistles written according to those who date all Pauline letters to the 2nd century CE? Were they written around the same time for the same communities? A few decades later? In the 3rd century CE? Something else?”

I hope to cover some of these questions in more depth in coming posts. In short, a major problem (not the only one) that I see with dating Paul’s letters to the first century is that we have to conclude that they made no significant impact at that time, and that Paul himself remained a nonentity until the mid-second century. How was it that his letters were suddenly discovered and collected so late? And then we find that the letters are not letters at all but patched quilts of different letters or writings. Historical rules of thumb start assessing dates from the time we find external evidence for documents. In this case, that is the mid second century. It is at that time that we have many writings interested in Paul, including the Pastorals, Acts of Paul and Thecla, Acts of the Apostles, emerging. The question that interests me is why this sudden eruption of interest in Paul at that time. As for communities being addressed in the letters, I have doubts that any of the letters were written to local communities. They may have headers saying that they were, but the contents actually suggest a more “catholic” audience. Example, at one moment the author is addressing converts from paganism, at another those from Judaism, another time he seems to be addressing everybody else, not even Christians.

P.S. Sorry for the long delay in replying. Just catching up again here.

Thanks Neil. You have carefully navigated a path through the documents to which you refer and explained a succinct and persuasive statement of a constructive charter for engagement with New Testament studies.

I am concerned that the essays quoted by Pattenden and yourself concerning the “Unbelieved” are asking for the supernatural to be given special treatment by historians. They argue that “objective historians should not discount, in advance, evidence that points to the existence or involvement of the Unbelieved [i.e. supernatural beings] in history”. Surely this is arguing for historians to do theology, contrary to your own final paragraph? They counsel against “dogmatic atheism” which is fine where what is meant is crusading atheism, but where this runs against uniformitarianism, surely they are entering a quagmire? Whilst you and Peter Brown are acknowledging the difficulties presented by Paul, the authors of the Unbelieved are asserting that they have identified a path for the reinstatement of Mary.

Hi Geoff. Yes, I do confess I have some problems with the Clossey et al’s three-part article and that is why I focussed on the first of their three proposals: humility before the sources. I could never expect outright (i.e. “in your face”) Christian apologists to work productively with secularists. I am thinking of those biblical scholars who would themselves fall into the “imperialist” mindset of the three-part article and likewise deny the role of the supernatural. Researchers of the historical Jesus and Christian origins, for instance, by and large speak of the disciples coming to believe, upon reflection and subjective experiences, in the resurrection and messiahship of Jesus. (Of such “critical” scholars, only N.T. Wright, as far as I know, argues for a literal resurrection.)

When the authors of the article say that sometimes the evidence for the “unbelieved”, meaning in our terms “the supernatural”, is sometimes as good as anything we could expect for natural events — e.g. multiple sworn testimonies — I do not agree. “Multiple sworn testimonies” for alien abductions, let’s say, are themselves sources that need to be respected and understood historically but are not in themselves proof of the reality of alien abductions. Multiple sworn witnesses have often been found in historical court and trial scenes to be false. Mass hysteria is a real phenomenon. Conspiracies are real events but that does not prove every conspiracy theory that takes possession of a population — e.g. the supposed designs of a powerful cabal of Jews controlling the world and manufacturing all its wars and economic fortunes — is real.

No. I cherry-picked. I zeroed in on the one proposal that I believe, at least theoretically, that all sides could agree on.

I think the problem is that too few of those who are considered critical scholars are interested in really doing history rather than historical fiction. They aren’t so much interested in determining what history has to say about a historical Jesus as they are in placing their fictional character of Jesus in a historical setting.

Dickson has responded to Pattenden, doubling down on appeal to authority; falsely equating consensus on climate change to consensus on the ‘the historical Jesus’; complaining Pattenden accused ancient historians of group-think; splitting the ‘biblical Jesus’ from ‘the historical Jesus’; and asserting that Mark, Q, the Pauline epistles and Josephus are key separate, independent sources.

https://www.abc.net.au/religion/john-dickson-revisiting-the-historicity-of-jesus/13730526

Sigh sigh sigh — it’s like re-reading James McGrath’s bromides. I have been doing so much reading, and varied and in depth, lately, that I have become bottlenecked, not knowing where to begin my next posts. At least you have given me a way to break the ice.

I have raised the following question at Wikipedia’s “Talk:Christ myth theory”:

I think the obvious answer is per Miles Pattenden, “Professional historians of Christianity” rather than a guild of biblical scholars.

<

blockquote><[U]nlike ‘guilds’ in professions such as law or medicine, it is not apparent what members of the ‘guild’ of biblical scholars have in common, other than a shared object of study and competence in a few requisite languages, and therefore what value an alleged consensus among them really has, especially on what is a historical rather than a linguistic matter. [Meggitt 2019, pp. 459–460).]/blockquote>

Also there is the point that what is considered “mainstream” varies between secular & non-secular camps.

• “Talk:Christ myth theory §. The secular & non-secular “equivalence” tactic”. Wikipedia.

For example, it is claimed that “Carrier is still not mainstream…” when citing the methodological failure of the criteria of authenticity and asserting a failure of the “entire quest for criteria”.

This is what passes for mainstream scholarship on Wikipedia:

• “Historicity of Jesus”. Wikipedia.

At least there is agreement that the “criteria” can not dissolve the varnish of Christian myth layered on top of Yesus.

• “The Next Quest for the Historical Jesus with James Crossley”. YouTube. Early Christian History with Michael Bird. 24 February 2022.

SIDENOTE: Surprisingly 🙂 I have just been notified that my cumulative 500+ WP edits have earned me access to “Wikipedia Library (WPL)” @ https://wikipedialibrary.wmflabs.org/

WPL goals:

Connect editors with their local library and freely accessible resources

Facilitate access to paywalled publications

Build relationships among editors, librarians, and cultural heritage professionals

Facilitate research for Wikipedians and readers

Promote broader open access in publishing and research.

How can Jesus Historicists and Mythicists Can Work Together?

First the have to agree on minimal “Historicity”.

Per the following, “Dr Sarah, do you have any issues with Carrier′s minimal “Historicity Jesus” definition? . Do you wish to add any qualifiers?”

Dr. Sarah (2018)responds:

I am certainly in favor of deprecating (i.e. make obsolescent) the name Jesus in reference to the historical personage Jesus b. Joseph/Pantera. I suggest using Yesus rather than Yeshu or Yeshua.

• e.g. Per the canonical gospels, Historicists assert that these literary narratives featuring god-Jesus contain biographical data for Yesus that can be extracted.

Is Pantera a nickname the Herodian Messiah’s father Antipater acquired during a stint leading troops in the Roman Army?

“Is Pantera a nickname the Herodian Messiah’s father Antipater acquired during a stint leading troops in the Roman Army?”

“Pantera”. RationalWiki. “Pantera may possibly have been the father of Jesus. The “Jesus son of Pantera” hypothesis has been promoted by James Tabor, who defends it primarily on textual grounds.”

Price, Robert M. (October 2006). “The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity ? James D. Tabor”. Religious Studies Review. 32 (4): 265–265. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0922.2006.00116_39.x.

“The paternity of Jesus”. RHEDESIUM.

https://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=7A37F227F1B7EEAC1299436AAF25880F Might as well pick a pseudo-history that actually is engaging like a novel.

Page 91 of 363 in this PDF: https://p303.zlibcdn.com/dtoken/d2e14957c98d9966d8c1b59c15a970b8/Herodian%20Messiah%20Case%20For%20Jesus%20As%20Grandson%20of%20Herod%20%28Joseph%20Raymond%29%20%28z-lib.org%29.pdf about Antigonus ben Antipater (a.k.a. Jesus) didn’t interest you?

I raised this issue @ https://iidb.org/threads/the-christ-myth-theory.26137/post-1027654

Crossley, James (10 August 2021). “The Next Quest for the Historical Jesus”. Medium.

“Join our Cloud HD Video Meeting”. Zoom Video.

Per a comment @“The Christ Myth Theory”. Internet Infidels Discussion Board.

This comment by Pattenden is surely questionable?

“Paul, the earliest writer to mention Jesus…”

How so? Is not Paul understood to have been writing in the mid to later part of the first century, 50s and 60s CE, while the first gospel is understood to have been composed around 70 CE?

I suppose that a case can be made that the author of Hebrews was writing earlier than Paul, which would be strengethened if Paul’s writings were dated into the 2nd century CE.

The case is based upon the fact that the Author of Hebrews makes no reference to the destruction of even interruption of sacrifices at Jerusalem’s temple, even though such events would have been useful for the author’s point.

Another supporting datum for a pre-Pauline date is the fact that the Author of Hebrews presents a Jesus as high priest at a heavenly sanctuary which would not be used in Pauline or post-Pauline Christian writings as far as I am aware, nor is associated with any other Christian movement as far as I am aware (and despite my pseudonym and my religion, I am aware of many Christian traditions about Jesus’s role).

Although I concede that an extinct creed with no descendents is not necessarily an older creed, the extinct creed from Hebrews (portraying Jesus as a high priest) combines with the lack of reference to the destruction of even interruption of sacrifices at Jerusalem’s temple as firm foundation for an argument that Hebrews is pre-Pauline.

I hope that these thoughts interest you.

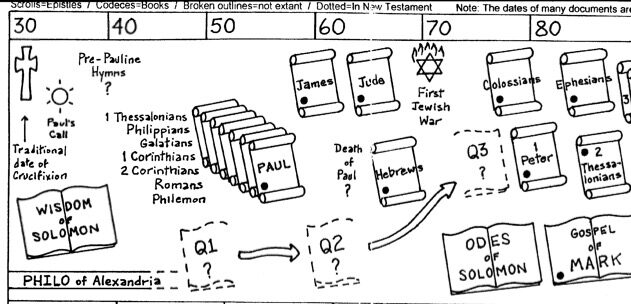

For interest here is a portion of a helpful chart produced by Earl Doherty and that was issued with his first book The Jesus Puzzle:

As noted by ABuddhist, one will see that details of the view expressed in this chart are open to debate.

And another timeline with conservative dates used within “mainstream” critical scholarship — from https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/: