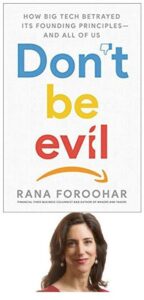

We begin with an interesting observation of Rana Foroohar, author of Don’t Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles – and All of Us . . . After outlining how Larry Page and Sergey Brin, co-founders of Google, arrived at their PageRank system that became the core feature of Google, Foroohar casts light on the engineers creating this new wonder:

We begin with an interesting observation of Rana Foroohar, author of Don’t Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles – and All of Us . . . After outlining how Larry Page and Sergey Brin, co-founders of Google, arrived at their PageRank system that became the core feature of Google, Foroohar casts light on the engineers creating this new wonder:

Now their bots could roam with impunity all over cyberspace, tagging, tallying—and potentially trespassing over the copyrights of anyone and everyone who had created the content they were linking to in the process, something that Google would eventually do at industrial scale when it purchased YouTube years later.

All perfectly innocent, right? And all for the greater good, naturally.

To Page and Brin, there was nothing nefarious about this. They simply sought to capture the knowledge tucked away in computer archives across the country to benefit humanity. If it benefited them, too, so much the better. It was the first instance of what later might be classified as lawful theft. If anyone complained, Page expressed mystification. Why would anyone be bothered by an activity of theirs that was so obviously benign? They didn’t see the need to ask permission; they’d just do it. “Larry and Sergey believe that if you try to get everyone on board it will prevent things from happening,” said Terry Winograd, a professor of computer science at Stanford and Page’s former thesis adviser, in an article in 2008. “If you just do it, others will come around to realize they were attached to old ways that were not as good….No one has proven them wrong—yet.”

In earlier pages, Foroohar opened the door to the educational and cultural background (from Montessori to Stanford) of Page and Brin that fostered this attitude.

This became the Google way. As Jonathan Taplin wrote in his book, Move Fast and Break Things, when Google released the first version of Gmail, Page refused to allow engineers to include a delete button “because Google’s ability to profile you by preserving your correspondence was more important than your ability to eliminate embarrassing parts of your past.” Likewise, customers were never asked if Google Street View cameras could take pictures of their front yards and match them to addresses in order to sell more ads. They adhered strictly to the maxim that says it’s better to ask for forgiveness than to beg for permission—though in truth they weren’t really doing either.

Oh, to have the freedom to create that only China can provide. . .

It’s an attitude of entitlement that still exists today, even after all the events of the past few years. In 2018, while attending a major economics conference, I was stuck in a cab with a Google data scientist, who expressed envy at the amount of surveillance that Chinese companies are allowed to conduct on citizens, and the vast amount of data it produces. She seemed genuinely outraged about the fact that the university where she was conducting AI research had apparently allowed her to put just a handful of data-recording sensors around campus to collect information that could then be used in her research. “And it took me five years to get them!” she told me, indignantly.

Like innocent children who believe they can create the brave new world . . .

Such incredulity is widespread among Valley denizens, who tend to believe that their priorities should override the privacy, civil liberties, and security of others. They simply can’t imagine that anyone would question their motives, given that they know best. Big Tech should be free to disrupt government, politics, civic society, and law, if those things should prove to be inconvenient. This is the logic held by the band of tech titans who would like to see the Valley secede not just from America, but from California itself, since, according to them, the other regions aren’t pulling their economic weight.

History and the humanities? Never bothered with them, but they do make a rich source of hyperlinks . . .

The kings (and handful of queens) of Silicon Valley see themselves as prophets of sorts, given that tech is, after all, the future. The problem is that creators of the future often feel they have little to learn from the past. As lauded venture capitalist Bill Janeway once put it to me, “Zuck and many of the rest [of the tech titans] have an amazing naïveté about context. They really believe that because they are inventing the new economy, they can’t really learn anything from the old one. The result is that you get these cultural and political frictions that are offsetting many of the benefits of the technology itself.”

Law? Ethics? We can’t code for those!

Law? Ethics? We can’t code for those!

Frank Pasquale, a University of Maryland law professor and noted Big Tech critic whose book The Black Box Society is a must-read for those who want to understand the effects of technology on politics and the economy, provided a telling example of this attitude. “I once had a conversation with a Silicon Valley consultant about search neutrality [the idea that search engine titans should not be able to favor their own content], and he said, ‘We can’t code for that.’ I said this was a legal matter, not a technical one. But he just repeated, with a touch of condescension: ‘Yes, but we can’t code for it, so it can’t be done.’ ” The message was that the debate would be held on the technologist’s terms, or not at all.

Human things require real humans to work humanely. Google removed the “Don’t be evil” motto from the introduction to its code of conduct in 2018. Continue reading “Silicon Valley’s Brave New World — and Chinese Communism may be its Beacon”