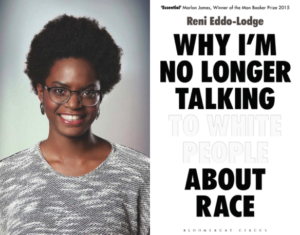

Reni Eddo-Lodge in her book Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race makes it clear that racism today is not mostly about malicious and ignorant people who hate others who are different from themselves. That kind of racism still exists but it is easy to identify and condemn: it is continued in white supremacist, anti-immigrant and far-right groups. Further, when Reni Eddo-Lodge speaks of white people she is not referring to every individual white person but to whiteness as a political ideology or identity. I believe that concept sounds bizarre to most white persons when they first hear it. It is only after reading the details of how persons of colour are handicapped at every stage of their lives that one can begin to become conscious of the privileges we white people take for granted. The challenges facing coloured people from infancy and on throughout their lives all too rarely make themselves known among whites in a white society. The problem is not white hostility so much as white ignorance. I think white people do have a responsibility to make the effort to listen to the experiences of minorities in their midst.

Reni Eddo-Lodge in her book Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race makes it clear that racism today is not mostly about malicious and ignorant people who hate others who are different from themselves. That kind of racism still exists but it is easy to identify and condemn: it is continued in white supremacist, anti-immigrant and far-right groups. Further, when Reni Eddo-Lodge speaks of white people she is not referring to every individual white person but to whiteness as a political ideology or identity. I believe that concept sounds bizarre to most white persons when they first hear it. It is only after reading the details of how persons of colour are handicapped at every stage of their lives that one can begin to become conscious of the privileges we white people take for granted. The challenges facing coloured people from infancy and on throughout their lives all too rarely make themselves known among whites in a white society. The problem is not white hostility so much as white ignorance. I think white people do have a responsibility to make the effort to listen to the experiences of minorities in their midst.

More quotes from Reni Eddo-Lodge’s book:

But this isn’t about good and bad people.

The covert nature of structural racism is difficult to hold to account. It slips out of your hands easily, like a water-snake toy. YouIn the same year that I decided to no longer talk to white people about race, the British Social Attitudes survey saw a significant increase in the number of people who were happy to admit to their own racism.4 The sharpest rise in those self-admitting were, according to a Guardian report, ‘white, professional men between the ages of 35 and 64, highly educated and earning a lot of money’.5 This is what structural racism looks like. It is not just about personal prejudice, but the collective effects of bias. It is the kind of racism that has the power to drastically impact people’s life chances. Highly educated, high-earning white men are very likely to be landlords, bosses, CEOs, head teachers, or university vice chancellors. They are almost certainly people in positions that influence others’ lives. They are almost certainly the kind of people who set workplace cultures. They are unlikely to boast about their politics with colleagues or acquaintances because of the social stigma of being associated with racist views. But their racism is covert. It doesn’t manifest itself in spitting at strangers in the street. Instead, it lies in an apologetic smile while explaining to an unlucky soul that they didn’t get the job. It manifests itself in the flick of a wrist that tosses a CV in the bin because the applicant has a foreign-sounding name.

The national picture is grim. Research from a number of different sources shows how racism is weaved into the fabric of our world. This demands a collective redefinition of what it means to be racist, how racism manifests, and what we must do to end it.

Those points in a black person’s life where the difficulties start:

- In school a black boy is three times more likely to be permanently excluded compared to the whole school population;

- By age 11, when preparing for his SATS, he will be systematically marked down by his own teachers (remedied only his work is anonymized and marked by other teachers);

- Happily a greater proportion of black students progress from sixth form to higher education but access to Britain’s prestigious universities is unequal and the black student is less likely to make it into one of the leading research universities;

- Black students are far more likely to finish their university education with a lower ranking pass than white students; (Recall that black students are more likely than white students to move into higher education so it is not likely that the gap is due to “lack of intelligence, talent or aspiration.” Almost 70% of university teachers are white, “a dire indication of what universities think intelligence looks like.”

- Even with a good education, having a non-white sounding name can mean a less likely chance of being called in for an interview despite the applications containing similar education, skills and work history;

- Black people are far more likely [links are to PDFs] to be unemployed than white people;

- “black people are twice as likely to be charged with drugs possession, despite lower rates of drug use. Black people are also more likely to receive a harsher police response (being five times more likely to be charged rather than cautioned or warned) for possession of drugs” (Report – PDF);

- British residents of African and African-Caribbean backgrounds are more than other ethnic groups to be sectioned into psychiatric wards; and to receive higher doses of anti-psychotic medication than whites; and more likely to remain as long-term in-patients;

- As the black person ages he is less likely to receive a timely diagnosis for dementia than white counterparts.

Commenting on the above hurdles (with my own highlighted emphasis),

Our black man’s life chances are hindered and warped at every stage. There isn’t anything notably, individually racist about the people who work in all of the institutions he interacts with. Some of these people will be black themselves. But it doesn’t really matter what race they are. They are both in and of a society that is structurally racist, and so it isn’t surprising when these unconscious biases seep out into the work they do when they interact with the general public. With a bias this entrenched, in too many levels of society, our black man can try his hardest, but he is essentially playing a rigged game. He may be told by his parents and peers that if he works hard enough, he can overcome anything. But the evidence shows that that is not true, and that those who do are exceptional to be succeeding in an environment that is set up for them to fail. Some will even tell them that if they are successful enough to get on the radar of an affirmative action scheme, then it’s because of tokenism rather than talent. enough to get on the radar of an affirmative action scheme, then it’s because of tokenism rather than talent.

and

Structural racism is never a case of innocent and pure, persecuted people of colour versus white people intent on evil and malice. Rather, it is about how Britain’s relationship with race infects and distorts equal opportunity.

Eddo-Lodge, Reni. Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. London Oxford New York New Delhi Sydney: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.