Earlier posts in this series: 25th August 2020 and 27th August 2020.

Then,

. . .

We come now to the third section of Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity and the one that is of special interest to me . . . .

Part 3. Biblical Narratives

The opening essay is by another scholar also of the University of Copenhagen whose work has been discussed before on Vridar, Ingrid Hjelm: “The Food of Life and the Food of Death in Texts from the Old Testament and the Ancient Near East“. Hjelm interprets Genesis 1-3 intertextually with the Mesopotamian myth of Adapa, the book of Proverb’s discourse on Wisdom and Folly, and 1 Samuel’s narrative of Nabal and Abigail, finally extending even to thoughts on the Lord’s Supper in the New Testament.

I have a special interest in the Adapa myth as is surely evident from having posted fifteen times on it so far. It is about a pre-Flood mortal, Adapa, who is given perfect wisdom by the god Ea but not eternal life. Adapa offends the gods and is called to give account. The god Ea, who gave him wisdom, deceives him so that he unwittingly rejects the gift of eternal life offered by a higher deity, Anu. The details are quite different but the motifs are the same as we read in Genesis: a mortal being deceived by a divine agent, becoming wise but losing eternal life, the “sin” and a curse. There is surely some connection but exactly what that is is not immediately clear. Hjelm explores the questions common to both myths. The temple of the gods in the Adapa myth is replaced by the divinity’s garden in Genesis. Hjelm points out that Thompson himself has noted that the woman already “knows the good” before she eats of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and that insight changes the way we read the story. Yet God has already planted the tree of life in the same garden, so why is it that God appeared from the outset (before “the fall”) to turn the attention of Adam and Eve from that tree? Asking such questions brings us even closer to the character of the interplay between the gods and Adapa in the Mesopotamian myth.

The second part of the essay is another fascinating examination of Wisdom and Folly in Proverbs vis à vis Abigail and Nabal (meaning “Folly”) in 1 Samuel 25, with once more the motif of eating specially prepared food. A snippet of the discussion:

In a comparative analysis of the goddesses Athirat, Qudshu, Tannit, Anat and Astarte in texts from the ancient Near East, inscriptions mentioning Asherah (and Yahweh) from Khirbet el-Qom and Kuntillet Ajrud and Old Testament texts, Broberg finds so much similarity in the symbol of Ashera’s linking of trees, snakes, fertility and woman that it is plausible that McKinlay’s ‘agents of God’ hide an Ashera goddess (Broberg 2014: 50-64).19 The use of the plural forms in Gen. l:26’s and 3:22’s ‘let us’ and ‘like us’ functions as an inclusio around this hidden goddess (Broberg 2014: 64), who is present at the creation as god’s wife, but in the course of the narrative is transformed to become Adam’s wife as the ‘mother of all living’ (Gen. 3:20; Broberg 2014: 59; cf. also Wallace 1985: 158). A similar transformation takes place when Abigail as David’s wife ‘is moved into the ranks of the many wives’ (McKinlay 2014 [sic – 1999?]: 82).

If, as argued by Broberg (2014: 61), Genesis 2-4’s woman/Eve narratives contain a conscious dethronement of Asherah similar to the anti-Asherah bashing the in the books of Kings (e.g. 1 Kgs 18:19; 2 Kgs 21:7; 23:4-7), it is likely that Proverbs 1-9 and 1 Samuel 25 are written as contrasting narratives, aiming at transferring Asherah’s positive traits as mother of all living onto the female figure. As heir of the life-sustaining qualifications of the fertility goddess, the wise woman secures the good life and holds death in check. (pp. 171f. Broberg 2014 = a Masters thesis at University of Copenhagen. My highlighting in all quotations.)

Where does the Lord’s Supper enter this picture?

The study of ancient myths may also add to our understanding of the Lord’s Supper as a radical transformation of drinking from the ṣarṣaru cup of Isthar in Near Eastern covenant ideologies’ confirmation and remembrance of the covenant. (p. 173)

But let’s move on. The next chapter pulls out for attention one of those very odd passages in Biblical narratives that seem to have no real connection with the surrounding text and seem to add nothing at all to the plot and appears to be nothing more than an outlandishly tall tale. It’s one of those “why did the author write that?” scenarios: “A Gate in Gaza: An Essay on the Reception of Tall Tales” by Jack M. Sasson.

Judges 16: 1 One day Samson went to Gaza, where he saw a prostitute. He went in to spend the night with her. 2 The people of Gaza were told, “Samson is here!” So they surrounded the place and lay in wait for him all night at the city gate. They made no move during the night, saying, “At dawn we’ll kill him.” 3 But Samson lay there only until the middle of the night. Then he got up and took hold of the doors of the city gate, together with the two posts, and tore them loose, bar and all. He lifted them to his shoulders and carried them to the top of the hill that faces Hebron.

Sasson asks how such a story was understood by its ancient audience. We have no motif for Samson’s visit to Gaza; the feat defies credibility even for a strong-man (given the size of city gates later rabbis deduced Samson’s shoulders spanned dozens of cubits; add to the weight and size we have a steep climb and journey of tens of kilometres). Why do Bible authors sometimes resort to what surely must have been acknowledged to be obvious fictions?

. . . the exaggerations are themselves the focus of the story, giving them a ‘fictionality’ that encourages transposal into other forms of comprehension, such as a parable or a paradigm. In such accounts, narrators tend to sharpen implausibility by multiplying clues, their main intent being to promote the didactic via the entertaining. In antiquity, any Samson reader acquainted with fortified cities would know that city gates, not least because of their size, bulk and weight, were not transportable on the back of any one individual, however mighty. . . .

Elsewhere in Scripture, narrators also use diverse tactics to alert perceptive readers or audiences on the fictionality of what lies before them by assigning moralistic or whimsical names to characters that no parents would wish on their children. Such a tactic is obvious in Genesis 14 with its series of the named kings of Sodom (Bera, ‘In Evil’), Gomorrah (Birsha,‘In Wickedness’) and one of their allies (Bela, ‘Swallower’, likely king of Zoar). (pp. 184f)

The answer involves a deeper discussion of the structure of the overall Samson narrative. Modern readers who are looking through a glass however piously dark for historical layers need to be pulled up by a realization that the original audiences were surely more astutely aware of “tall tales” when they were exposed to them.

Next is Bob Becking’s “Deborah’s Topical Song: Remarks on the Gattung of Judges 5“. Becking’s opening paragraph goes directly to a point that has been stressed repeatedly over the years on this blog. (I also probably owe the lesson to reading Thompson years ago, especially his Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written and Archaeological Sources or at least to others also influenced by Thompson.)

When I first met Thomas L. Thompson in Dublin 1996, he stressed the view that before even thinking about drawing historical conclusions from a text, one should first and foremost try to understand the Genre of that text. His argument ran as follows: the way in which a text is moulded into its form is informative about the message a writer wanted to communicate at the time of his/her writing. The story of the past is often so mutilated by the fabrics of a specific Gattung that no historical conclusions can be drawn (see Thompson 1999). (p. 190)

Older commentaries posit that the Song of Deborah is “one of the oldest remaining pieces of Hebrew literature”. But archaeological evidence and our growing understanding of Hebrew have conspired to throw up alternative dates from the monarchic through to the Roman periods! How likely is it, then, that the song contains genuine historical information? For Becking an answer to that question can be elicited through an understanding of the genre of “topical song”.

A topical song is a hymn that focuses on what for the composer is a recent and important event. A topical song could be seen as a newspaper in hymnic form. In pre-literate societies the communicative aim of a topical song was twofold: to inform and to convince. Like a newspaper message, such a song informed hearers about what had happened. . . . At the same time, a topical song is never without an evaluation. . . . In other words, like a newspaper message, a topical song is never without ideology. . . .

Although topical songs generally refer to recent events, they sometimes persist long after the event narrated. In that case a topical song is part of the cultural memory of a community referring to a shared historical memory. A case in point is the hymn ‘Jerusalem’, the lyrics of which were written by William Blake. They were partly based on the legend that Joseph of Arimathea accompanied Jesus to Glastonbury, and also inspired by the atrocities of the ‘dark Satanic mills’ of the Industrial Revolution. (pp. 191f)

Becking’s essay sets out grounds for reading the Song of Deborah as one of several topical songs or hymns in which were embedded “written sediments of a cultural memory that earlier on would have been transmitted in oral form.”

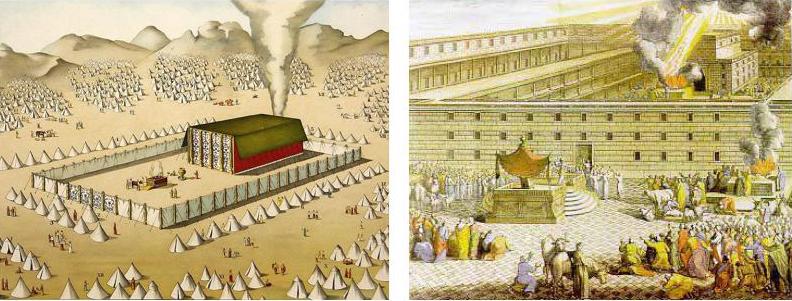

For those of us who have wondered how we ought to interpret not just the similarities but also the differences between the Tabernacle in the Book of Exodus and the Temple in the Book of 1Kings we now have the fourth essay in part three of the festschrift: “How Jerusalem’s Temple Was Aligned to Moses’ Tabernacle: About the Historical Power of an Invented Myth” by Rainer Albertz. This essay ushers the reader on another fascinating journey of possibilities to explain the many curiosities in the biblical texts.

Albertz explains why we can conclude that the Tabernacle texts in the Pentateuch were composed later than the descriptions of Solomon’s Temple in 1 Kings. The next interesting stop is the evidence for later scribes redacting some of the Temple accounts to update them with details matching the Exodus account of the Tabernacle — and what this activity indicates about the religious-political life of the times:

Thus, in aligning Jerusalem’s temple as closely as possible with Moses’ tabernacle, the Chroniclers intended to bestow upon their sanctuary the highest degree of legitimacy and authority in the eyes of the Samarians. We know that the Samarians had also accepted the Pentateuch as their Holy Scripture; and if we trust a much later note from Josephus (Ant. 18.85), the Samarians likewise legitimated their own sanctuary on Mount Gerizim by referring to vessels from Moses’ tabernacle that were buried next to it. Thus, there were competing claims to the mythic past making this even more powerful. Therefore, the Chroniclers worked hard to prove that their temple in Jerusalem was the rightful successor to the normative tabernacle of Moses, that is, the only legitimate sanctuary of YHWH. (p. 205)

Later descriptions of the Temple in the Second Temple era likewise speak of Tabernacle features being introduced (e.g. curtains) that appear nowhere in the biblical account of Solomon’s temple so that Albertz comments

This short case study has shown that literary passages of the Hebrew Bible, which are evidently unhistorical, can develop an astonishing power that shapes not only the further literary history of other biblical passages but also elements of the historical reality. The priestly tabernacle texts from the book of Exodus are a good example of this. The dynamic power has to do with the decision made in the Judean and Samarian communities of the fourth century BCE to accept a bigger part of their literary tradition, the tôrat Mošeh, as authoritative. By doing so, they did not only concede that the concepts and rules of the Pentateuch should have more or less influence on their lifestyle, but they also obtained a powerful basis, on which they could found their theological claims and the legitimacy of their cultic institutions. Because of this authoritative textual corpus priests and other responsible persons felt obliged to change the appearance of the Jerusalem temple in order to align it with aspects of Moses’ famous tabernacle. Thus, we should perhaps not classify all texts from Genesis to 2 Kings as ‘mythic past’ on the same level because of their common contrast to modem historiography. Some of them, especially those of the Pentateuch, possess more ‘mythical dynamic’ than others. I agree with the statement Thomas Thompson made in his dissertation: ‘In fact, we can say that the faith of Israel is not an historical faith, in the sense of a faith based on historical event; it is rather a faith within history’ (see Thompson 1974: 328-9). I would like just to emphasize that this faith – expressed by biblical texts – cannot only change the mind and behaviour of people, but is also able in some way to change historical reality. (pp.207f)

Keith Whitelam made that point of a “mythical dynamic” changing “historical reality” disturbingly relevant even up to the present day in The Invention of Ancient Israel.

There are four more chapters to cover which I hope to do in a future post.

Niesiolowski-Spanò, Lukasz, and Emanuel Pfoh, eds. 2020. Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays In Honour of Thomas L. Thompson. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies. New York: T&T Clark.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!