Continuing my outline of Celine-Marie Pascale’s article The Weaponization of Language. Wherever possible hyperlinks take you to the direct source online.

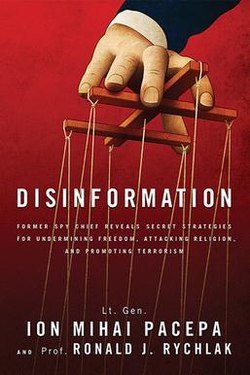

Stalin coined the word ‘dezinformatsiya’ in 1923 “to describe false information spread systematically through media and public announcements to intentionally confuse or mislead publics.” What is of particular interest at this time, however, is the use of the term “fake news” to “decry reality as fake”. Examples are cited in relation to Syria, Myanmar, Spain, Venezuela, and no doubt we can all think of many more.

In these examples, the charge of ‘fake news’ is a form of disinformation in itself. Governments are using the charge of ‘fake news’ to reshape reality as they attack information and people that they want to discredit. Sherine, one of Egypt’s most famous singers, jokingly implied it was not safe to drink from the Nile and was arrested and sentenced to six months in jail for insulting the country by ‘spreading fake news’ (BBC, 2018). As is evident in these examples, the charge of ‘fake news’ is levied by government leaders to dismiss or to attack people and ideas that are verifiably true.

(Pascale, 905f. Italics original; bolding added)

From the Schwartz article linked in the above quote:

“These governments, they’re pushing the boundaries of what it’s possible to get away with in terms of controlling their national media,” said Steve Coll, dean of the Columbia Journalism School, “and there’s no question that this kind of speech makes it easier for them to stretch those boundaries.”

White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders pushed back against the idea that Trump bears responsibility. “This story is really ridiculous,” she said in an email. “The president isn’t against free speech but we do think reporting should be accurate.”

The spread of the phrase has come against a backdrop of rising violence and persecution against journalists . . . .

Trump’s go-to insult has become such a touchstone that members of far-right groups or political parties in countries like the Netherlands or Germany often write “fake news” in English in their tweets, said Cas Mudde, an international affairs professor at the University of Georgia.

“I have seen it particularly in social media used by radical right leaders who have been clearly influenced by Trump’s use,” he said. “Even if they have a tweet in Dutch, there will be a hashtag #fakenews in it.”

Returning to Pascale:

Disinformation campaigns are designed to consolidate power by provoking reactionary responses that sustain epidemics of social unrest. For example, the US intelligence community pummeled Chile with disinformation in order to unseat the democratically elected President Salvador Allende and install Augosto Pinochet (Carter, 2014). Recently, researchers have documented that Russia targeted specific racial groups in the United States with more than 80,000 posts and thousands of ads that mimicked the style of Black Lives Matter activists in order to stoke racialized conflict and unrest (Associated Press, 2018). Each of these postings proliferated through social media re-postings.

Disinformation might contain complete falsehoods or partial truths, or it might distort reality by representing an unusual circumstance as a common one. Disinformation campaigns also often incorporate conspiracy theories which delegitimize mainstream media and are used to target people and ideas. For example, Nazi ideology, rife with conspiracies theories regarding Jews, is one of many examples of a disinformation campaign. Jewish conspiracy theories remain today. In 2018 Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán forced the closing of the Central European University (CEU), a private university funded by George Soros, an American of Hungarian and Jewish origin. Orbán, who has promised to defend his Christian homeland, claimed the CEU was part of a plan by Soros to flood Hungary with non-Christian immigrants (Stanley, 2018).

Conspiracy theories are a complete subject of their own and I hope to be posting soon on some new academic publications that have come out these past two years addressing their nature, reasons, and function in today’s political climate.

Meanwhile,

“The president’s proclivity to twist data and fabricate stories is on full display at his rallies. He has his greatest hits: 120 times he had falsely said he passed the biggest tax cut in history, 80 times he has asserted that the U.S. economy today is the best in history . . .

“Nearly 25 times, he has claimed that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh was No. 1 in his class at Yale University or at Yale Law School. . . .

“This is one of those facts that can be easily checked with a Google search, yet the president persists with his falsehood.”

(Kessler et al., 2018)

Trump is known to have made the same false claim more than 120 times (Kessler et al., 2018). Donald Trump seems to be drawing from Lenin’s old aphorism that a lie told often enough becomes the truth. However, in the internet age Lenin’s aphorism could be updated to ‘If you make it trend, you make it true’ (DiResta, 2018). Truth and politics have never been on the best of terms (Arendt, 1967 link is to PDF) but we have entered new territory. It isn’t only the numbers of lies that pose a threat.

Consider that Trump’s lies are different in kind, not just in quantity, from typical people. When ordinary people lie, we orient toward the truth in order to make our lies seem plausible (Carson, 2016; Frankfurt, 2005– link is to PDF). We want our lies to been seen as being true; this is the nature of deceit. Ordinary people craft lies with an eye to preventing ourselves from being exposed for having lied. This has not been the case for Trump, whose lies are not masked. Indeed, he openly bragged about lying to the Canadian Prime Minister about trade deficits. Trump is not attempting to get away with a lie. Rather, Trump’s lies convey an impression that he wields unconstrained power: he can say whatever he wants to say, and the world just has to take it. Perhaps it is even a little sweeter for him, when people know he is lying but can do nothing about it. To the extent that he seems to have impunity it is because he does not stand alone; he is part of a comprehensive system that brought him to power and ensures his survival. Even when media identify lies, a significant part of the population does not care – indeed he is part of a cohort of world leaders who adopt a very similar approach. Trump’s communication has been successful – even while those of us wedded to facts may think otherwise. Efforts to demonstrate the falsity of his claims are important yet never adequate. This is precisely why we, as sociologists, must pay attention to the use of language – not just matters of fact.

Disinformation campaigns online are a powerful, effective, and inexpensive means to generate political and social chaos. Disinformation and propaganda working together do more than create factions and tensions between them. They place factual reality itself at risk. The greatest danger is not that lies will be accepted as truth and truth defamed as lies, but that ‘the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world – and the category of truth vs. falsehood is among the mental means to this end – is being destroyed’ (Arendt, 1967: 50). Reality itself becomes more contingent and less objectively real. Reasoned debate is replaced by emotional spectacles.

(Pascale, 908)

Next: Mundane Discourse….

Omg — after I posted the above I turned to twitter and what did I see there but this as if right on cue. . . . Continue reading “The Weaponization of Language (Part 4) – Disinformation and fake news”