We hear over and over that Australian nationalism was forged in the crucible of war.

We hear over and over that Australian nationalism was forged in the crucible of war.

The Australian War Memorial preaches this belief with its Forging the Nation exhibition.

The renowned war historian C.E.W. Bean made the message clear in his history of Australia in World War 1:

And then, during four years in which nearly the whole world was tested, the people in Australia looked on from afar [and] saw their own men flash across the world’s consciousness like a shooting star. Australians watched the name of their country rise high in the esteem of the world’s oldest and greatest nations. Every Australian bears that name proudly abroad today; and by the daily doings, great and small, which these pages have narrated, the Australian nation came to know itself…

We are repeatedly reminded of headlines like the following:

- The Great War, including Gallipoli, was the crucible in which the Australian identity was first forged

- “The Symbol of Our Nation”: The Slouch Hat, the First World War, and Australian Identity

- The birth of a nation? Gallipoli, trial and trauma

But it’s not true. It is a myth. Australian nationalism was alive and flourishing in the years preceding and following Federation in 1901. An Australian identity — the one that is propagandized today with its stress on mateship and egalitarianism — was there in the cultural, social and political life of Australians before 1914.

I wish I could locate the source of the words now but I recently heard a woman being interviewed on Late Night Live, I think it was, remarking that the Great War broke Australia. It changed us as a nation. We lost our confidence not just from the immediate trauma of the four years of battle but from the many traumas of trying to rebuild lives in the years following.

With Federation in 1901 the big question was what sort of nation Australians wanted to build:

‘’A new demesne for Mammon to infest?

Or lurks millenial Eden ’neath your face?”Was the continent to see repeated the evils of other civilizations, the ravages of war, the co-existence of great wealth and abysmal poverty, the rigid class structure of privilege, or was it, on the other hand, free of the taint of older societies, to produce a civilization in which the individual dignity of man had full respect?

(Greenwood, 199. The poetry is from the Bernard O’Dowd’s prize-winning poem challenging the emerging nation in 1900 to ask what sort of society it would make of itself.)

The mateship was there long before Gallipoli as anyone who has read Henry Lawson’s poetry should know.

Bitten deep into the consciousness of the men and women who espoused the Labour cause was a belief in the importance of solidarity, of sticking together, of being able to rely on one’s mate. (200)

And it wasn’t confined to the labouring class, either:

While the more advanced liberals had in common with the leaders of political Labour a belief in experimentation, a sense of Australianism, a recognition of the necessity for remedying social injustice by State action, and, in the larger view, an optimistic acceptance of the social democratic doctrine of progress, all this sprang from genuine conviction, for the faith to which they held and by which they acted was their own and not merely a pale reflection of Labour doctrine. (203)

Australian values (good and bad) were being self-consciously “defined and firmly established” from at least as early as 1901. There was a confidence we would scarcely recognize today, a confidence in the ability to transform and make a more just society, one free of poverty and inequality and exploitation (205).

There was a tone of self-confidence about the pre-1914 nationalist creed. The world was young, and despite the turmoil and depression of the nineties there was an idyllic and anticipatory assumption of future triumphs. Power and creative vigour, the impulse to assert the dignity of the ordinary man through a new Australian social order and the exhilaration of building towards an independent and native cultural tradition all belong to the movement. (207)

Geographic realities meant that the nation had to come together to work through a centralizing power. (See Australia and the United States – Interesting Comparisons for a comment on Australia’s attitude towards central government.) There was also the labour movement’s felt need to take control of the power that had formerly been used to oppress them into accepting unsafe and intolerable conditions. But the core values were shared by both sides of politics:

Humanitarian liberalism, whether of the Deakin [i.e. Liberal] or Fisher [i.e. Labor] variety, was in the ascendant until the war of 1914. Liberal and Labour governnicnts testified in action to their belief in the efficacy of State enterprise. Their social and economic principles were worked out in the field of public policy, and by experimentation they endeavoured to forge new instruments of social and economic justice . . . . Social aims, however, touched almost all legislation . . . . (210-11)

So what were some of the achievements of that “social experiment” of the pre-War years? What particulars are worthy of being remembered and celebrated and embraced as proud achievements of a nation? Here are a few:

| 1872 | Overland Telegraph Line: Connecting Adelaide and the rest of Australia, through Darwin, with England by means of a single wire in 1872, was one of the greatest engineering achievements of the nineteenth century. |

| 1872 – 93 | Free, compulsory and secular education introduced in Victoria (72); SA and Qld (75); NSW (80); Tas (85); WA (71/93) |

| 1879 | Australia’s first national park — (now Royal) National Park — was created in 1879 just south of Sydney. It was only the second in the world.

“Originally formed to address public health concerns about overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in large cities, today’s national parks often focus more on ecological conservation.” |

| 1884 | Hugh Victor McKay invents Sunshine Harvester — which could harvest, thresh and winnow wheat — with dramatic economic consequences for the nation. |

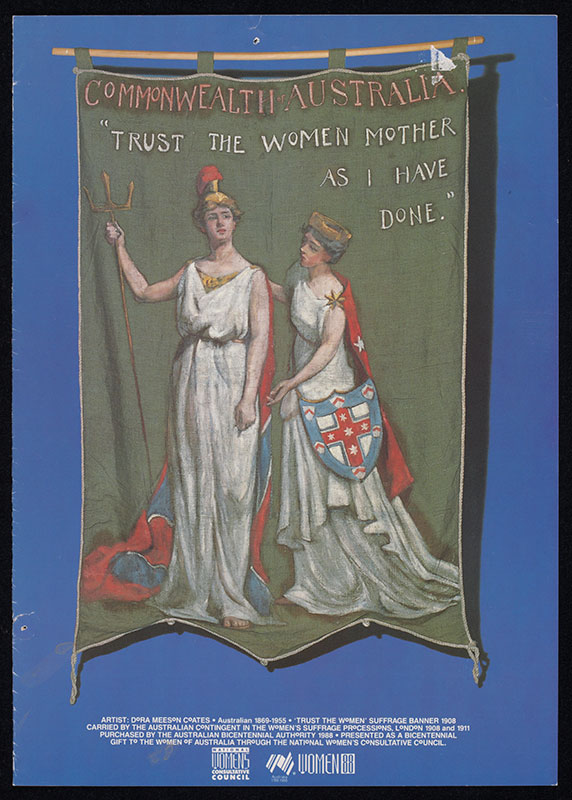

| 1894 | South Australia was the first electorate in the world to give equal political rights to both men and women. |

| 1899 | First Labour Government in the world was elected in Queensland |

| 1901 | Post and Telegraph Act — Commonwealth Departments of postal and telegraph services enabling direct contact between central govt and national community, not through provincial mediums. |

| 1902 | Australia became the first nation to introduce equal federal suffrage. The enactment of the Commonwealth Franchise Act in that year allowed women to both vote and stand for election. |

| 1904 | Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration established with both Liberal and Labor support: also designed to facilitate the organization of representative bodies of employers and employees, to enable the States to refer industrial disputes, and to create conditions favourable to conciliation. ‘The stress was placed on conciliation and on legalizing voluntary agreements through “the sanction of the court’’. (213) — Reid: “Australia can win victories and set examples which will teach the rest of the world.” (214) |

| 1907 |

|

| 1908 | Legislation introducing national age and invalid pensions.

. . . an agreed national aim and both Liberal and Labour parties (220) emphasized the psychologically important point that old age pensions were not a charitable allowance but a right in recognition of past services (221) |

| 1910 | In the 1910 elections the Liberal party sponsored the establishment of a comprehensive scheme of social insurance . . . (230) |

| 1911 | Commonwealth Bank established by Labor Government

A people’s bank, managed by the people’s own agents, and backed by the credit of the national government, was a concept not without popular appeal. (229) |

| 1911-12 | Trans-continental railway (1911/12) (222) |

| 1912 | Maternity Allowance introduced

Payment was regarded not as a baby bonus but as a maternity allowance “for the protection and care of the mother which is tantamount to the care of the unborn child”. Labour was bent on asserting two principles: that the scheme should be non-contributory and that it should apply generally without means test with a view to removing the reproach of charity. (230) |

| 1913 | Australian Institute for Tropical Medicine, was established in Townsville in 1913 and was Australia’s first medical research institute. . . the Institute made a significant contribution to understandings about how Europeans could live in and adapt to tropical Australia. |

| 1913 | In the 1913 campaign, Cook proposed a contributory scheme covering sickness, accident, unemployment, widowhood and maternity. Opposition (230) |

Social progress did not end in 1912 of course. But I have tried to highlight some of the more significant pioneering reforms. It was not a bad start in just ten years:

- the first nation to introduce equal suffrage,

- a bold attempt to enable constructive conciliation between unions and employers,

- a basic wage that enabled a decent living for a man, wife and three children

- age and invalid pensions not as a charity but as a recognition of worth and a right

- maternity allowances, again as a right, not a charity

- free, compulsory, secular education for all

Another list could be made for cultural evolution of a national identity, in painting, film, literature, music, and (sigh!) sport. Many Australians may have felt themselves as living in something of a cultural backwater in the 1950s and early 60s but that, too, may have had something to do with interruptions to cultural life with the wars and their immediate aftermaths.

My point: I don’t think we would have to scratch too deep to find plenty of material that would enable us to meaningfully celebrate a national identity without resorting to the war. Not that war should be ignored. But it does seem to me to have become a funnel for a lot of political propaganda in recent decades, a propaganda that puts limits on questioning our all too frequent involvement in war.

Greenwood, Gordon. 1955. Australia: A Social and Political History. Sydney, NSW : Angus and Robertson.

See also,

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

It could even be argued that WW I and II tried to fatally overemphasize Australia’s relation to the rest of the British Empire.

If anything, the wars thereby hindered Australian independence. Which was better furthered by most of the other cultural forces you mention