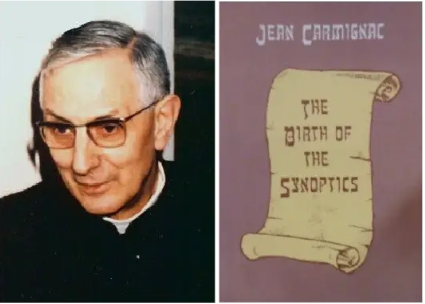

Here is a little more background for anyone interested in Jean Carmignac’s hypothesis that the Gospels of Mark and Matthew were originally written in the Hebrew of the Dead Sea Scrolls. I have excerpted sections from Carmignac’s preface and first chapter. The bolded highlighting is mine to enable a quick perusal of key points.

From the Preface:

. . . . May I be pardoned above all for having written this book. I decided upon it only after a good deal of soul searching. For my original plan was to pursue my research as far as possible, to present it in a number of large technical volumes and only then to offer my research to the public at large in a little volume which would be less forbidding. But several friends convinced me to begin with this little volume. They made the point that I ran the risk of being six feet under before finishing the larger works and that for several years my research has, in no way, altered my conclusions so that I can therefore honestly begin to share it with others. The future will show if I have been correct in paying attention to these friends.

In this work, I have endeavored to make sure that it contains no polemics. I name no one nor do I have anyone in mind. I know very well that the views set forth here are not in conformity with the current vogue in exegesis. I have not attempted to refute arguments which may support opinions different from my own. I am proposing the results of research pursued since April 1963, more than twenty years. My research has convinced me, and I would like to share my firm beliefs with others. I furnish proofs which have led me to one or another conclusion; I would have been able to give many others, but these would have gone beyond the general purpose of a book which was intended for the public at large. These I am reserving for more technical works. Thus readers will now be able to compare what I think with what they are hearing said all around them. It is up to them to weigh the arguments and to judge freely for themselves.

In order not to stifle these poor readers, I have decided not to give all the specific references to works which I have utilized, save in certain particularly important cases. Complete bibliographies will appear in the larger volumes which are presently in preparation.

In order to show clearly the subjective character of this work, which is merely the presentation of my personal research, I would have preferred to title it: “Twenty Years of Work on the Formation of the Synoptic Gospels.” An objection was raised that this title is too long and not particularly catching. But it is more exact.

I believe myself sincere in my quest for the truth. If I am presented with convincing proofs, I will always be ready to improve and even to modify my present conclusions.

From Chapter I: Elaboration of the Hypothesis

It was merely by chance that I happened to become involved with the question of the formation of the Gospels. But once started, I allowed myself to be guided by the logic of the work.

While translating the texts of Qumran, I discovered many connections with the New Testament and each time I prepared an index card. Once the translation was finished I had a huge stack of index cards, and I considered them sufficiently important to use in composing a “Commentary on the New Testament in the light of the Documents of the Dead Sea.” I wanted to begin with the Gospel of Mark. In order to facilitate the comparison between our Greek Gospels and the Hebrew texts of Qumran, I tried, for my own personal use, to see what Mark would yield when translated back into the Hebrew of Qumran. I had imagined that this translation would be difficult because of considerable differences between Semitic thought and Greek thought, but I was absolutely dumbfounded to discover that this translation was, on the contrary, extremely easy. Around the middle of April 1963, after only one day of work, I was convinced that the Greek text of Mark could not have been redacted directly in Greek and that it was in reality only the Greek translation of an original Hebrew. The enormous difficulties which I had envisioned for myself had all been resolved by the Hebrew-Greek translator, who had transposed word for word and who had even preserved in Greek the order of the words preferred by Hebrew grammar. For the Greek sentence, much more flexible than the Semitic sentence, allows for a great deal of liberty in the positioning of words, whereas in Semitic languages the placing of the various parts of speech is determined by more precise rules.

How to explain this fact, that the Greek of Mark adhered so readily to the laws of Hebrew grammar? Is it enough to suppose that the Greek text had been redacted by a Semite who continued to think in the categories of his mother tongue? In order to respond to this question, it is important to pursue the experiment of translating back into Hebrew. . . . . [I]t is important to use this Qumranian Hebrew, a little different from biblical Hebrew and greatly different from Mishnaic Hebrew.

As my translation gradually took shape, my conviction was reinforced: Even a Semite, having learned Greek later on in life, would not have permitted the stamp of his mother tongue to come through so thoroughly; he would have, occasionally, at least, taken some liberty; he would have, from time to time, made use of an expression current in Greek. But no. We have here the literal, carbon copy or transparency of a translator attempting to respect, to the greatest extent possible, the Hebrew text which he had before him.

. . . .

Evidently, the style of the Gospels is not literary, i.e., more or less artificial; it is simple, natural and quite close to the oral style. The redactor writes almost as he speaks. We can neither compare his work with Greek scholars such as Demosthenes or Plato, nor with the Greek of the authors who were almost contemporaries of the Evangelists such as Philo . . . or Josephus . . . or Plutarch . . . .

This is not the problem: Simple or complicated, natural or artificial, a style respects the genius of a language, its implicit philosophy, its unconscious personality. But the language of the Gospels appeared to me more and more like a non-Greek language expressed in Greek words. It was the language to which I had become accustomed through my research into the Books of Chronicles and on the Dead Sea Scrolls; but this language, instead of being expressed in Hebrew words was being expressed in Greek terms. . . .

The first explanation which comes to mind is to attempt to draw upon the mother tongue of the Evangelists. Being of Semitic origin, they continued to think according to Semitic categories, and they expressed themselves clumsily in a Greek language of which they had a poor command (like myself when I speak English). Not at all! The Greek of the Gospels is not poor Greek: it does not contain mistakes in agreement, or mistakes in conjugation, or clear-cut mistakes against syntax. Can we suppose the intervention of a reviser who corrected errors? This still wouldn’t suffice, for this Greek, which is not a bad Greek is not even a clumsy Greek. It is not like “my” English, which is a mixture of French and English, in which the influences of both languages do not always harmonize, in which the turns of phrase are clumsy and awkward. In the Gospels we have neither clumsiness nor awkwardness. On the contrary, there is a simple and spontaneous beauty, one which is not the beauty of the Greek but rather the customary beauty of Semitic prose. The Gospels were not composed by Semites who had a poor knowledge of Greek and who spoke or wrote some type of jargon, a sort of middle ground between both languages. They have been redacted by people who wrote well, but according to Semitic patterns which were translated into a very correct Greek by other people who sought to make a tracing or a literary rubbing of the words of the original. The appearance is perfectly Greek, too Greek to have been derived from people who possessed a poor knowledge of this language; but the reality is perfectly Semitic, so Semitic that it could only have come from people expressing themselves very naturally in their mother tongue. To put it in another way: the Greek of the Gospels is not a poor Greek, nor a clumsy Greek: It is the good Greek of a translator who has respect for a Semitic original, who conserves the flavor and the scent of the original.

If the language of the Gospels is not that of Semites who had a poor awareness of the Greek language, might we imagine it to be the work of Greeks imitating the Semitic style? The Septuagint, that is to say, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, enjoyed such prestige that one might have had the tendency to adopt, more or less consciously, its tone and coloration. Perhaps. But are we aware of a single work of a Jewish or Christian author, which reproduces its very special style? That here and there authors of the Gospels had taken a particular formula or a particular turn of phrase from the Septuagint is quite natural. But what a tremendous difference between these occasional borrowings and a continual imitation! Even preachers who are most infatuated with a “biblical style” are not given to expressing themselves constantly like Isaiah or the Psalms, or Mark, John, or Paul. . . .

It was correct to appeal to the example of the Septuagint, which is a literal translation made from Hebrew (or Aramaic). This is exactly the case with the Gospels, which are themselves also the faithful translation of the Semitic originals. From this point of view the comparison is perfect. But to suppose an imitation, conscious or not, of the style of the Septuagint from one end of the Gospels to the other is to leave the realm of probability !

. . . .

It is here that a real problem arises. Why is this hypothesis of a Semitic original so frequently pushed aside without serious examination? . . . .

It has sometimes been remarked that specialists in the New Testament have too great a tendency to isolate themselves in Greek grammar and to neglect the study of Semitic languages; whereas specialists in the Old Testament, more accustomed to the Hebrew, recognize more easily the traces or carbon copies of Hebrew in the Gospels. This is perhaps true for some. In any case, it is true for me. My eleven years of work on the Books of Chronicles (from 1943 to 1954) had prepared me for the study of the manuscripts of Qumran (from 1954 to 1963) before I embarked upon the study of the Gospels (in 1963).

In summary, then, these are the ideas which matured within me while I set about the retroversion or translation of Mark back into Hebrew.

In order to confirm or show the weakness of them, I also translated parallel passages of Matthew and Luke back into Hebrew and the same evidence immediately jumped to my eyes in exactly the same way for these works.

Matthew is totally as Semitic as Mark and, in his case, we do possess the testimony of numerous Fathers of the Church (since Papias, toward the year 130) who affirm knowledge of a Hebrew Matthew. Since many authors admit that Matthew depends on Mark . . . why not say: “since Mark is prior to Matthew, he must be like him in Hebrew?”

The case of Luke is different. He has clearly composed his Gospel in Greek, as the beautiful Greek phrase which constitutes his prologue (1:1-4) proves. Moreover, in his Gospel, we find the most unexpected Semitisms sprinkled about in the midst of turns of phrases of a most elegant Greek. In order to explain all of this, the most normal hypothesis is to suppose that he was working upon Semitic documents, translated very literally, which he inserted into his own redaction, sometimes touching them up but sometimes preserving their roughness.

Little by little, the connections between the three Synoptic Gospels became clearer to me and, without having sought, in a special fashion, to resolve the famous “Synoptic problem,” an overall hypothesis began gradually to take shape, based on the facts which I was gathering and the consistency of which I was eager to verify. But I willingly acknowledge that it is nothing very original since all its details have already been proposed by various scholars. I do not consider it as definitive since I have not yet translated all of Matthew and of Luke back into Hebrew. But, while waiting for new facts which may oblige me to improve upon it, or perhaps even to dismiss it, I believe that I can consider this overall view as a working hypothesis, provisionally valid.

. . . .

Carmignac, Jean. 1987. Birth of the Synoptic Gospels. Translated by Michael J. Wrenn. Chicago, Ill: Franciscan Pr.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Definitely very interesting. I agree that there are similarities between the Qumranic writings and the Gospel of Mark. I’d like to read more about his notes on that. However there are some glaring issues here.

“Even a Semite, having learned Greek later on in life, would not have permitted the stamp of his mother tongue to come through so thoroughly; he would have, occasionally, at least, taken some liberty; he would have, from time to time, made use of an expression current in Greek.”

Purely speculative. This sounds like typical nonsense from NT scholars.

“Evidently, the style of the Gospels is not literary, i.e., more or less artificial; it is simple, natural and quite close to the oral style.”

This is impossible given what we know of the literary dependencies in Mark. I’d like to see how he would address the multitude of scriptural references.

“They have been redacted by people who wrote well, but according to Semitic patterns which were translated into a very correct Greek by other people who sought to make a tracing or a literary rubbing of the words of the original.”

“the Greek of the Gospels is not a poor Greek, nor a clumsy Greek: It is the good Greek of a translator who has respect for a Semitic original, who conserves the flavor and the scent of the original.”

This sounds to me like claims made by Qists who talk about how Luke couldn’t possibly have borrowed from Matthew because Matthew is so beautifully written that no one would dare undo some of Matthews scenes. It’s just total conjecture.

What he’s saying is that he doesn’t believe a person could exist who could write both fluent Hebrew and fluent Greek. He’s claiming that no individual ever existed, and thus this had to be written in two stages by two people, one of which was fluent in Hebrew, the other of which was fluent in Greek. I don’t buy that fundamental claim.

I have always believed that the writer of Mark must have been fluent in Hebrew, for they have far too deep a mastery of the OT scriptures. Who else would have such a mastery other than someone who had learned the scriptures from their youth and who was involved in religious instruction? Such a person would almost certainly be a Jew who would have learned in Hebrew.

So, that the author of Mark knew Hebrew I don’t doubt at all, and indeed expect as much to be true.

“But what a tremendous difference between these occasional borrowings and a continual imitation!”

But yet, what we see in Mark is that Mark is virtually a continuous stream of scriptural borrowing apparently from the Septuagint! So it appears very much that in fact Mark WAS engaged in “continual imitation”.

“It was correct to appeal to the example of the Septuagint, which is a literal translation made from Hebrew (or Aramaic). This is exactly the case with the Gospels, which are themselves also the faithful translation of the Semitic originals. From this point of view the comparison is perfect. But to suppose an imitation, conscious or not, of the style of the Septuagint from one end of the Gospels to the other is to leave the realm of probability !”

But yet, this fact is actually in evidence! Mark is in fact an imitation of the Septuagint from one end to the other!

Unfortunately, I know nothing of any languages other than English, so this is a very difficult matter for me to address. I wish I had the time and inclination to dedicate to learning these languages, but alas that’s never going to happen.

I do respect his knowledge of the languages and what he has to say about this matter, but there seems to be some deep flaws in his logic and suppositions. I’d also like to have his take on the Greek texts from Qumran. How does he compare the Greek from Qumran to the Gospels? Is he aware of all of the literary references in Mark? I’d like to see specific examples and see if he’s citing instances of borrowing from the Septuagint.

The fact that he says that there is no other example like this, expect the Septuagint, but then discounts the idea that Mark may have been leaning so heavily on the Septuagint, seems quite problematic. He has basically provided the explanation for why Mark would appear as it does, and then discounted if out of hand.

I myself have increasingly suspected that the person who wrote Mark had some connection to the Qumranic community. I’ve found many parallels between Mark and Qumranic texts, at least in concept and style, though not to say direct borrowing. It’s also clear that the writer of Mark was a master of his craft. The Gospel of Mark is surely not the only thing this person ever wrote. I’m very open to the possibility that we have other works from this writer. I think its possible that works from the same author exist in the Qumran stash.

I definitely would like to see his notes on links between the Gospels and Qumran.

Thanks for posting this.

So, were the “larger works” ever published? He died in 1986 and I can’t find a reference to a larger work.

If he did not, has anyone else taken up his notes and carried on his task?

In earlier posts on Carmignac I included links to sites where his work is explored by other scholars. If those sites are typical then it appears Carmignac’s ideas have been taken up by Catholic scholars with an interest in establishing sources that are “closer to the historical Jesus” than anything found elsewhere. (That was the bias Nanine Charbonnel spoke of and Carmignac’s own self-confessed interest.) I have come across a few other works that seem to discuss midrash in the gospels on the belief in a Hebrew text behind our canonical versions but they are all in French. My knowledge is limited, of course, but so far it appears that this research is primarily (Catholic) French-based.

That, of course, is nothing more than my opinion which may well be poorly informed. I am still in early days of learning about it all.

What R. G. Price said! I couldn’t have expressed my difficulties with Carmignac’s musings better.

-DF

Until we have a non-Greek 1st century gospel in hand, most of this musing is not helpful.

Of course, we don’t even have a Greek 1st century gospel, or even a Greek 2nd century gospel save in snatches from quote-happy clerics like Irenaeus, so..

Therein lies the difficulty of the task. We are betting on shadows, trying to guess the picture of the puzzle from a few edge pieces.