Immersed as we are in the heritage of the Christianity of the Crucified Christ it is easy to forget (if we ever knew) that there was another side to Christian origins. Try to imagine what gave rise to a Christianity that knew nothing of the pierced, broken body and shed blood of Jesus as the way to salvation. Imagine their sacred writings said nothing at all about the members of the church being united by eating the body and drinking the blood of their saviour but instead enjoined the following:

Immersed as we are in the heritage of the Christianity of the Crucified Christ it is easy to forget (if we ever knew) that there was another side to Christian origins. Try to imagine what gave rise to a Christianity that knew nothing of the pierced, broken body and shed blood of Jesus as the way to salvation. Imagine their sacred writings said nothing at all about the members of the church being united by eating the body and drinking the blood of their saviour but instead enjoined the following:

Now concerning the Eucharist, give thanks this way.

First, concerning the cup:

We thank thee, our Father, for the holy vine of David Thy servant, which You madest known to us through Jesus Thy Servant; to Thee be the glory for ever..

And concerning the broken bread:

We thank Thee, our Father, for the life and knowledge which You madest known to us through Jesus Thy Servant; to Thee be the glory for ever. Even as this broken bread was scattered over the hills, and was gathered together and became one, so let Thy Church be gathered together from the ends of the earth into Thy kingdom; for Thine is the glory and the power through Jesus Christ for ever..

But let no one eat or drink of your Eucharist, unless they have been baptized into the name of the Lord; for concerning this also the Lord has said, “Give not that which is holy to the dogs.”

But after you are filled, give thanks this way:

We thank Thee, holy Father, for Thy holy name which You didst cause to tabernacle in our hearts, and for the knowledge and faith and immortality, which You madest known to us through Jesus Thy Servant; to Thee be the glory for ever.

Thou, Master almighty, didst create all things for Thy name’s sake; You gavest food and drink to men for enjoyment, that they might give thanks to Thee; but to us You didst freely give spiritual food and drink and life eternal through Thy Servant.

Before all things we thank Thee that You are mighty; to Thee be the glory for ever.

Remember, Lord, Thy Church, to deliver it from all evil and to make it perfect in Thy love, and gather it from the four winds, sanctified for Thy kingdom which Thou have prepared for it; for Thine is the power and the glory for ever.

Let grace come, and let this world pass away. Hosanna to the God (Son) of David!

If any one is holy, let him come; if any one is not so, let him repent. Maranatha. Amen.

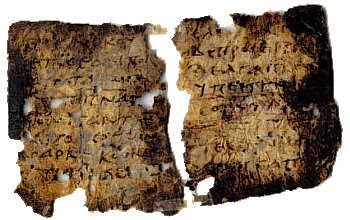

That is from the Didache (did-a-kee), or Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, that some (Wikipedia says “most”) scholars today date to the first century. That’s possibly around the same time Paul was writing his letters and the time the first gospels were being written.

Compare the instructions for our more familiar branch of Christianity (1 Cor. 11:23-26 NASB):

For I received from the Lord that which I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus in the night in which He was betrayed took bread; and when He had given thanks, He broke it and said, “This is My body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of Me.”

In the same way He took the cup also after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in My blood; do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of Me.” For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until He comes.

That looks like two very different Christian factions from the earliest years of Christianity’s origins.

We know in letters of Paul we read of attacks on “false” apostles who teach a “false” Christ. Does the Didache represent one of those factions Paul saw as a threat?

The Gospel of Mark is sometimes considered a “Pauline” gospel because, in part, of its overlaps with Paul’s teachings on faith, forgiveness, the law. The same gospel presents the twelve apostles as dim-witted failures despite being the first to “know” Jesus.

I am fascinated by the Didache’s picture of the bread being broken as a symbol of the church being scattered. That echoes the gospel saying of Jesus looking on the multitudes in need of a shepherd (Mark 6:34), and Ezekiel 34:5’s lament that the sheep were scattered for want of a shepherd; and Psalm 23 with its idyllic image of the sheep as one following the good shepherd and Mark 13:27’s promise that angels would be sent out to gather the elect from the four winds, from the farthest end of the earth and the farthest end of heaven.”

Zechariah 13:7’s hellish vision of the sheep being scattered because the shepherd was struck down is surely the very reverse of the above.

Surely this is a very different Christianity from the one that we have inherited through Paul and the canonical gospels. For Paul the broken body and blood of Christ were the core icons of his faith. How can we imagine a Christianity without them?

How do we explain the emergence of the belief system that produced the Didache? How can we explain such two opposing forms of the faith from the same first century?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

In point’v fact Didache is proprly

did-a-KHee ie ‘kh’ as in loCH or KHan, not locK

Dus marana-tha! evoke a certain nostalgia for an aramaic speaking pursunality?

The Didache was written by folks who valued peace, the orthodox canon by those who valued power and didn’t mind killing others to get it.

I presume the rhetorical question at the end means you’ve got more to say on the subject.

My “explanation” has two pieces:

First, Jesus was not, in fact, crucified.

Second, the end of the story, from the entry into Jerusalem to the empty tomb, was originally written by someone who wanted a symbolic allegory describing the gist of the prophet’s teaching and why it was rejected, with an ending that said the teaching would come to fruition at some later time.

I find it makes perfect sense if you take the Parable of the Sower as a guide to how to interpret the rest of the allegory.

Thank you for posting this. I was struck by a few things while reading the Didachee. As you point out, it appears to be evidence of a tradition distinct from that of Paul, but (and I might just need to read it a little closer) I also didn’t see anything to connect this with the Gospel stories. Jesus is mentioned a few times around the Eucharist section as “Thy Servant,” but there’s nothing I can see to tie him to an earthly Jesus, so this could actually be evidence of belief in a heavenly Jesus. Also, regarding the scattering and gathering of the bread, is this a metaphor for the diaspora? Or might it possibly have any roots in the scattering, gathering and reassembly of Osiris?

Going back to the heavenly Jesus possibility, I think back to the discussion on Philo and Zechariah 6:9-13. My recollection is that Philo identifies “Branch/the East/Rising” (“one of many names”) as an angel/agent/aspect of God and seems to reference Zechariah 6, where a Joshua son of Jozadak (aka Jesus son of God the Righteous, or Jesus son of God’s Righteousness) is crowned as God’s high priest who will build the temple of the Lord and rule on his throne. Which seems similar to the fellow described in 2 Samuel 7, who will be a son of God that will raise up his kingdom and throne. Samuel also tells us that this fellow was of the seed of David – likely where Paul was informed of this information.

I could see how a sect, similar to modern bible “coders” looking for secret wisdom, could start to connect that these two people were one and the same, and then going forward to connect other scripture to “learn” more about him, until there was an entire gospel built around him (that would then later be historicized through Gospels). If this (basically the Carrier hypothesis) is some approximation what happened, it’s quite likely that some sects or people kept going after others stopped and discovered more and more “secret” information about Jesus. This would explain how some sects might recognize a Jesus as a heavenly agent of God, while others would come to “preach Christ Crucified” (1 Corinthians) and that there was “another Jesus” (2 Corinthians) that was being preached.

Let me point out that there’s a great deal of material on the Didache here: http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/didache.html

Somewhat off topic but here is the sourse of the Jesus agraphia in Dididache 14

Malachi

1:11

My name will be great among the nations, from where the sun rises to where it sets.

In every place incense and pure offerings will be brought to me, because my name will be great among the nations,” says the LORD Almighty.

Didache

Chapter 14.

For this is that which was spoken by the Lord: “In every place and time offer to me a pure sacrifice; for I am a great King, says the Lord, and my name is wonderful among the nations.”

From the Didache :”Even as this broken bread was scattered over the hills, and was gathered together and became one, … ”

Booker, 2018-03-15 :”Also, regarding the scattering and gathering of the bread, is this a metaphor for the diaspora? Or might it possibly have any roots in the scattering, gathering and reassembly of Osiris? ”

Maybe and no.

It is appears to be an allusion to John 6 in which Jesus handed out morsels of bread to his supplicants and received whole loaf(s) in return, and perhaps to : Ecclesiastes 11 (KJV) 11 Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days.

The phrase appears to be a parable about proselytizing and community formation.

The answer to this is very simple and well-documented; Early Christians were of two types. Jewish, and Gentile (non-jewish, commonly Pagan). These two groups came from different backgrounds and had their own perceptions on what God is and what God isn’t. Pagans had no problem believing that the Son of God would take birth as a human. It was not unique to them. For the Jews, however, they could in general not accept that God would take a human birth, be a baby, grow up, etc. and thus different practices developed, one for those who believed Jesus is God Himself, and one who Believed that Jesus is not God Himself but the prophet fully empowered by God (called Shakti avesh Avatar in Sanscrit).

Throughout Paul’s letters, he is seeking to unify these two original factions and apease both of them. Hope this helps.

also, This topic is discussed at great length here https://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/n/new-testament-of-the-bible/about-the-new-testament-of-the-bible

im not being facetious, the New Testament Cliffs Notes are really good, including what I have written above.

Perhaps 1 Cor. 11:23-26 is not Pauline in origin. Detering and Price consider I Cor. 15:3-11 an interpolation. It similarly begins: “For what I received I delivered to you….”

Maybe. But the equation of bread and body seems to be rather Pauline than Markan. Mark used titular identifications (“So the Son of Man is Lord, even over the Sabbath”, “You are the Christ”) or similes and metaphors, but not such surprising equations of unequal things. Paul often did it (“For they drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was Christ.”, “You are the body of Christ”).

What, if any, use of the Didache has been made in addressing the synoptic problem? Consider:

Didache — “Lord has said, ‘Give not that which is holy to the dogs.’”

Matt. 7:6 — “Give not that which is holy to the dogs….”

Thomas 93 — “Give not that which is holy to dogs….”

Similar, but differing considerably is Mark 7:27 — “… for it is not meet to take the children’s bread and cast it to the dogs.”

(Luke & John are silent.)

Also, if the Didache predates the gospels, then there must have been either an oral tradition of Jesus sayings and/or a ‘Sayings’ gospel in existence.

I don’t believe that the Didache has much in common with the hypothesized “Q” sayings gospel.

On the other hand, the idea that Jesus was an illiterate peasant (Crossan and lots of others) simply doesn’t feel right. Matthew and John portray him as educated and call him “rabbi.” He’s portrayed as reading from the scrolls in a synagogue. Either Matthew or Luke has him discussing the Law with the priests in the temple as a young man. His inner circle would have either been literate or would have learned.

I expect that there was a fairly large amount of written material floating around, including the hypothetical Passion Narrative that I alluded to earlier: http://www.earls ychristianwritings.com/passion.html .

Oops. The url got mangled. It’s http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/passion.html .

A proposed Synoptic problem solution linking Matthew and the Didache

https://www.alangarrow.com/synoptic-problem.html

The Didache attributes ‘Give not that which is holy to the dogs.’ to ‘the Lord’; but elsewhere the teachings are developed as those of the anonymous author(s) eg. going the extra mile. We find this happens in canonical epistles also. G.Mt seems to me to have in part developed out the Didache rather than the other way about, the sayings developed out of it and attached to the Jesus figure, which figure also developed in part from previous writings such as those of Philo. An oral ‘sayings’ tradition or ‘sayings’ gospel, while there may have been such – even if only ephemerally, would not be a neccessity.

The falsely so-called epistles of Saint Paul are forged Anti-Marcionic non-epistles from the middle or late second century. Any attempt to date them to the time before the fall of Jerusalem is absurd. Likewise, it is necessary to refrain from making statements about any version of Christian faith in the first century.

The Didache-faction was plausibly a threat for Marcion, possible author of proto-Galatians before the additions made by the anti-Marcionite Roman Catholic scribes; but there is no reason to assume that the extant copies of Didache themselves have not been manipulated and mutilated successively, just as all falsely so-called early Christian writings. Markus Vinzent specifically complains of the problems of providing a solid critical edition of the Didache, and the impossibility of discerning a clear history of redactions from much later variants, specifically the interaction with the development of the synoptics.

Don’t underestimate pagan influences: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2010/apr/03/easter-pagan-symbolism