As pointed out in the previous post historians of ancient times have criticized an approach to ancient sources that they call the nugget theory or the Christmas cake analogy. The historical sources need to be analysed at a literary level in order to first determine what sorts of documents they are and what sorts of questions they can be expected to answer, and then they need to be tested, usually by means of independent corroboration. Independent corroboration must be contemporary as a rule for reasons set out in The evidence of ancient historians.

The prevailing view among New Testament scholars of Christian origins is an unashamed application of the nugget and Christmas cake that is said to be invalid, fallacious, erroneous, misguided, unsupportable, in defiance of what we know about how ancient authors worked, by other historians of ancient times.

Contrary to the ways other professional historians approach their ancient sources biblical scholars have sought to find tools to find the nugget of historical truth or the cake of what comes reasonably close to what really happened.

Criteria of authenticity

The tool they have used to do this has been their criteria of authenticity. Never mind that even some of their own peers, other biblical scholars, have conceded that these criteria are logically flawed and incapable of really establishing genuine history behind the texts (gospels), as long as they say they can use them “judiciously”, “with caution”, they’ll manage okay.

Memory theory

More recently some biblical scholars have found another tool to replace “criteriology”. They have found memory theory. Never mind that they don’t quite use that theory in the way its original founders intended, used “judiciously” and “with caution” it can surely bring the modern historian just a little closer to what might have actually happened, so they say.

Clear glass or stained glass windows

In an earlier post, Gospels As Historical Sources: How Literary Criticism Changes Everything, we saw the analogy of two different types of windows at play. The biblical historian sees the gospels as a window that needs to be “looked through” in order to try to identify the history on the other side. The opposing view sees the gospels as stained glass windows to be admired as literary productions in their own right.

Digging for that pot of gold

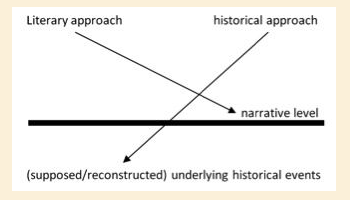

The biblical historian also uses the analogy of digging, presumably as in an archaeological dig, and helpfully provided this diagram to illustrate the way the biblical historian proudly worked:

That diagram is an epitome of all the analogies used by trained historians in their condemnation of that method.

See Gospels As Historical Sources: How Literary Criticism Changes Everything for a discussion of the two windows, the diggers, the nugget miners, and the Christmas cake eaters.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

These theories all start with the presumption that the source text is historical.

My point of view is that large numbers of people only care about historicity from thousands of years ago to justify modern political actions. They respond to criticism of historicity as if you are pulling on one of the cards at the bottom.