Everybody “knows” that when Israel declared its independence the Arab states amassed their armies and marched into Palestine hoping to throw all the Jews out into the sea, but that tiny David overcame their onslaught and as if by divine miracle drove them back behind their borders. Everybody “knows” that again in 1967 tiny Israel launched a preemptive attack on her surrounding Arab neighbours who were secretly preparing to deliver a surprise attack to wipe Israel off the map. Everybody “knows” that Israel has lived daily in the shadow of a perpetual threat to her very existence from an alliance of Goliath-sized Arab neighbours.

Everybody “knows” that when Israel declared its independence the Arab states amassed their armies and marched into Palestine hoping to throw all the Jews out into the sea, but that tiny David overcame their onslaught and as if by divine miracle drove them back behind their borders. Everybody “knows” that again in 1967 tiny Israel launched a preemptive attack on her surrounding Arab neighbours who were secretly preparing to deliver a surprise attack to wipe Israel off the map. Everybody “knows” that Israel has lived daily in the shadow of a perpetual threat to her very existence from an alliance of Goliath-sized Arab neighbours.

Is that the reality, though?

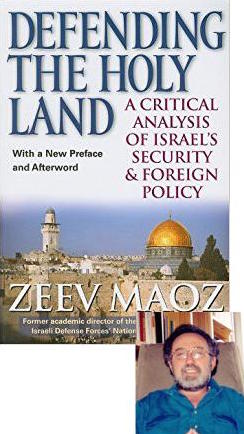

Defending the Holy Land: A Critical Analysis of Israel’s Security and Foreign Policy by Zeev Maoz provides excellent insights into the “behind the scenes” realities of Israel’s wars and responses to real and imagined threats since 1956. For some basic info on Zeev Maoz see his Wikipedia entry; see also the publisher’s promotion of Defending the Holy Land.

Some excerpts (all bolding and formatting is mine):

We noted that the Arab states never exerted a concentrated social, political, and military effort in converting the dream of destroying the state of Israel into reality. The rhetoric of genocide and politicide was not backed up by anything close to the kind of resources and diplomatic coordination that was required for realizing this dream. Most Israeli politicians and scholars accepted the fundamental asymmetry in resources as a constant in the strategic equation of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Yet nearly nobody bothered to ask why — if the Arab states were so committed to the destruction of the Jewish state — they refrained from investing the resources required for such a “project.”

Maoz, Zeev. Defending the Holy Land (p. 574). University of Michigan Press. Kindle Edition.

Even if the human and material military burdens of the Arab states were to stay at their current levels, the Arabs could put together an incredible economic and social challenge to Israel simply by forming a military coalition that pooled their resources in an effective and rational manner. Saudi Arabia, for example, spends $22 billion on defense annually, more than twice the Israeli defense budget. It has fairly free access to American and Western European weapons markets. Had it decided to put its military hardware and financial resources at the disposal of this Arab coalition, Israel would have been under extremely precarious strategic conditions. Again, no shots have to be fired in order to erode Israel’s capacity to meet these challenges.

Finally, consider an effective implementation of the Arab boycott on Israel and on companies trading with it and couple it by a threat to deny or limit the exports of oil to Israel’s main trading partners. If the oil-rich Arab states had been willing to suffer the economic costs of such a threat, Israel’s trade with the outside world would have significantly declined. Since Israel imports much of its basic needs in food, energy, and industrial inputs, it would not have been able to survive economically. Thus, there exist several scenarios — none of them far fetched if we follow the logic of Israeli politicians and strategists — in which Israel loses the big war without having a single shot fired at it.

But the Arab states never came close to materializing the elements of these scenarios. Why?

Continue reading “Reality Behind Arab Threats to Destroy Israel”