As a contributor to The Resurrection of Jesus William Lane Craig attempts to tidy up some looseness in the arguments for the resurrection of Jesus made by N. T. Wright in his voluminous opus, The Resurrection of the Son of God.

I quote here Craig’s recasting of Wright’s argument in a “more perspicuous” structure. He precedes his recasting with this:

[A]ttempts to explain the empty tomb and postmortem appearances apart from the resurrection of Jesus are hopeless. That is precisely why skeptics like Crossan have to row against the current of scholarship in denying facts like the burial and empty tomb. Once these are admitted, no plausible naturalistic explanation of the facts can be given.

He then presents the freshly polished argument:

1. Early Christians believed in Jesus’ (physical, bodily) resurrection.

2. The best explanation for that belief is the hypothesis of the disciple’s discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb and their experience of postmortem appearances of Jesus.

2.1 The hypothesis of the disciples’ discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb and their experience of postmortem appearances of Jesus has the explanatory power to account for that belief.

2.2 Rival hypotheses lack the explanatory power to account for that belief.

2.21 Hypothesis of spontaneous generation within a Jewish context

2.22 Hypothesis of dreams about Jesus

2.23 Hypothesis of cognitive dissonance following Jesus’ death

2.24 Hypothesis of a fresh experience of grace following Jesus’ death

2.25 And so forth

3. The best explanation for the facts of Jesus’ empty tomb and postmortem appearances is the hypothesis that Jesus rose from the dead.

3.1 The resurrection hypothesis has the explanatory power to account for the empty tomb and postmortem appearances of Jesus.

3.2 Rival hypotheses lack the explanatory power to account for the empty tomb and postmortem appearances of Jesus.

3.21 Conspiracy hypothesis

3.22 Apparent death hypothesis

3.23 Hallucination hypothesis

3.24 And so forth

In short, I think that Wright’s book is best seen as the most extensively developed version of the argument for the resurrection of Jesus from the fact of the origin of the disciple’s belief in Jesus’ resurrection, an argument that may be supplemented by comparatively strong, or even stronger, independent arguments of Jesus and, then, for his resurrection. Wright’s book is an invaluable reference work and a benchmark of resurrection scholarship. (pp. 147-8)

Resurrection scholarship? In my day job I am busily involved with the coordination of research data in medical scholarship, environmental and life sciences scholarship, indigenous cultures scholarship and much more. I am also involved in making this data and research publications from a wider range of scholarship areas safely preserved and openly accessible to the world. Maybe it’s my secular and naturalistic bias, or is it my bias for scholarship grounded in rigorous methodologies that genuinely produce new knowledge or ways of understanding and using current knowledge, but I find the idea of including in my areas of responsibility something called “resurrection scholarship” quite bizarre.

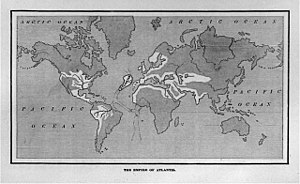

Reading William Lane Craig’s “strengthened” cast of Wright’s argument is like reading a classics professor arguing that the only sensible accounting for Plato’s and others’ beliefs in Atlantis is that they heard utterly credible and reliable reports about it from sources who ultimately knew about the ruins of a great civilization submerged beneath the sea; and the only sensible way to account for these utterly credible and reliable reports is that Atlantis must have been a great and proud civilization ruling a vast empire before its ruin and loss to the waters. Any other explanation is hopeless. That is why sceptics have to row against the current of scholarship and deny facts like the now lost ruins of Atlantis beneath the Atlantic Ocean.

Related post: Atlantis, another 21st century myth

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I find it hard to get excited about resurrection debates. Craig might argue he has presented a hypothesis which makes best sense of the Scriptural data (and I think he’s done a reasonable job; alternative hypotheses such as the swoon theory are simply laughable by comparison) but that still doesn’t prove it actually happened. Historicity of the Gospels notwithstanding, the resurrection is necessarily an article of faith, not something we can demonstrate empirically.

” alternative hypotheses such as the swoon theory are simply laughable by comparison”

Why is the swoon theory laughable? People who seem to be dead do sometimes spontaneously come back to life.

It is possible that Jesus was not permanently dead when he was removed from the cross. J of A puts him in a tomb where he is tended by a doctor. He recovers, is carried out that night into J of A’s house. Because they are all religious people, they all (including Jesus) say ” God has miraculously restored J to life”.

I prefer the vision theory myself, but I don’t think either theory is laughable.

And what happened in the next chapter? After all of his followers were thrilled to see he wasn’t dead after all, or that he had been restored to life just like the daugher of Jairus or Lazarus or the Shunnamite woman’s son or the son of the widow of Nain, they all decided to start a missionary movement to tell everyone Jesus wasn’t dead anymore, and to prove it they sat him on a donkey and paraded him around all the streets of Jerusalem, and some believed and some didn’t, and those who did started the whole new religion about the man on the donkey who was once in the tomb.

Not exactly. He was still a condemned criminal, so he stayed in hiding till he recovered his health and strength. (This is why he pops up in disguise or meets his followers in closed rooms.) Then he decided Jerusalem was too hot for him. “Keep the faith, lads. I’ll be back,” he said, and headed off to Kashmir, where he became a greengocer, married a very nice Kashmiri girl, and lived happily ever after. Well, not quite ever. He died of old age. His tomb is there, so it must be true. (His tomb is in Japan, too, which is really ingenious of him.)

Alternatively, he remained in hiding for quite a while, doing a bit of preaching, but didn’t really recover his health and strength and so “ascended to Heaven”.

Craig’s “fact” about the discovery of the empty tomb skips a step. We don’t have the “fact” of the disciples discovery of the empty tomb – we have the story of disciples discovering the empty tomb. Craig has to roll back his explanatory hypotheses to account for the story of the empty tomb first, and only then should we proceeed to his other arguments.

Of course, the discovery of the empty tomb is part and parcel of the historical reliability of the gospels, which is something Craig refuses to do once this is brought up. It’s a bit disingenious on his part, but works rhetorical wonders on the ignorant masses that he’s trying to convince. Historically, there’s a higher probability that the crucified Jesus was thrown in a mass grave after crucifixion instead of burial in a tomb whose description betrays post 70 CE provenance.

It appears to be a historical fact that early Christian converts were scoffing at the idea of their god choosing to raise corpses.

On Craig’s account, the body was given to a secret Christian supporter to look after, and then went missing.

If a Scientologist was given evidence damaging to Scientology to look after, and then 3 days later, it was found that the safe in which it was kept was empty, should we conclude that a miracle had happened?

Especially if not one person for 50 years ever puts his name to a document saying he had ever seen an empty safe?

NT Wright believes the body of Jesus was transformed into a new type of matter, never before seen on Earth.

Contrast his willingness to believe in new types of matter, on no more than anonymous reports in unprovenanced old books, with the thoroughness with which real scholars treated recent claims of faster-than-light travel.

The difference in standards between Wright and real scholars is so astonishing that a miracle must have occurred to have Wright’s work accepted as scholarship.

Not only is there missing the little detail that it is a story of a missing tomb, and not an empty tomb itself, that we have to work with, as JQ observes, but we also have that missing detail about how the news was passed from the eyewitnesses to everyone else — unless one wants to add more miracles like flames of fire sitting on tops of apostolic heads as they were heard to speak in every language under the sun.

William Crane Leg likes to say the words “explanatory power,” but wouldn’t the best explanation of the “facts” attempt to explain all the elements of the stories? He focuses on what he thinks are undisputed elements — namely, where he thinks the narratives agree. But what about all those points in which the storytellers disagree?

Suppose we had four sources of the JFK assassination. One says the motorcade was traveling west on Elm St. The second says they were traveling east. The third says Jackie was driving, and they were taking a shortcut across the Grassy Noll. The shortest account says he was shot, but nobody told anybody about it.

The resurrection, if it happened, must have been the most memorable event the disciples ever witnessed (or almost witnessed). It would have been seared into their brains the way 9/11 or the Challenger disaster is seared into ours. How does the so-called “best explanation” explain the multiple, vast, and irreconcilable differences in the gospels?

———

Later, that day, two unnamed cabinet members were walking from the White House to Capitol Building. JFK joined them and walked with them. “What is — uh — going on?” asks Kennedy. “Haven’t you heard? The President was shot!” They walk together and go into the Congressional Cafeteria. As they’re breaking bread together, JFK disappears. And the two guys look at each other and say, “That was the President!”

If the above story were true, why wouldn’t the storyteller give us their names? Why didn’t they recognize the risen President? Shouldn’t we suspect that it’s just a rumor? Even if the story ended with a strong statement that the witnesses steadfastly believe it’s true, and we can trust them, why should we? Who am I supposed to believe — the person telling the rumor, or the guys in the story that he invented?

In pre-blog days I used to write little “press releases” of the resurrection appearance accounts. Two said they happened in Galilee and the other two in or near Jerusalem.

But you know how it is with eyewitnesses of car-crashes. Two will tell you it happened in London and the others will say it was in New York. But these little differences of detail are evidence of authenticity, of course.

William Lane Craig boasts that no more than a quarter of Bible scholars doubt the empty tomb.

I can’t check his figures, but imagine trying to convict somebody of stealing a loaf of bread when a quarter of the witnesses called claim they doubt there was a loaf of bread in the first place.

If the evidence is not good enough to convict somebody of stealing a loaf of bread, how can similar evidence be put forward as proof that somebody rose from the dead?

I am sure William Lane Craig is contactable and would also be willing to share with us how may of these scholars are from seminaries, how may believe Jesus talks to them in mysterious or prayerful ways today, and so forth.

You mean “open-minded” scholars? According to Eddy and Boyd, proud proponents of the “open historical method,” the fact that the these seminary scholars believe miracles can happen proves they aren’t closed minded critics.

Similarly, proponents of the “open scientific method” are open to the idea that the best scientific explanation of natural phenomena might be the action of gods, demons, angels, ghosts, goblins, fairies, elves, etc. Only scientists with a naturalistic bias would restrict themselves to the material world.

Imagine if only 75% of biologists agreed about some particular critical data point for theory of evolution, like say succession in the fossil record or endogenous retroviruses. Creationists would have a field day.

I was at a Jesus Seminar meeting once and began to ponder the background of my colleagues. It turned out that, as far as I could tell, (and the Four Gospels book has lots of little bios, including mine) all of them had either attended seminaries, become ministers of the gospel, or both… with the exception of myself and one other. I spoke to him about this and he said, “not so fast. I had five years training in the Jesuit novitiate.” So I was it. I also noticed the tendency of secular historical Jesus scholars both professional and amateur to give antitestimonies, and I heard a lot of those at the Jesus seminar after hours. I began to think that I’m the only secular HJ scholar who hasn’t ever lost his faith. Never had it, never lost it.

I’ve often heard the argument that belief in miracles is no more or less an historical methodological position than disbelief in miracles is. The two positions are supposedly equivalent. They, of course, will believe in this or that miracle of Jesus, mainly the resurrection. When you ask for an example of a miracle they believe in that isn’t Christian, they have none to offer. Ask a Protestant scholar of this type for an example of a miracle by a Catholic saint that they will affirm, they have none to offer. If you cannot give an example of a credible non-Christian miracle, then you really are stuck having to admit your “historical methodological position” is faith based.

The empty tomb seems to me to be completely credible. The whole story is credible. Why is there such a problem? Wealthy pious Joseph of A wanted Jesus’ corpse removed before the sabbath started, it was placed in his expensive rock cut tomb. After the sabbath he immediately had his men remove it to a standard burial place. The women arrived and it was gone. What’s not to believe?

Hoo boy! Why is it that the most clear-headed people can be the most infuriating! 😉

That’s both interesting and depressingly unsurprising. It reminds me of the old joke about those who take up studies in psychology do so to sort out their own issues. Only it doesn’t seem to be a joke in this case. Exceptions granted, of course. It probably relates to why I generally find a richer mine of pubications among biblical topics that do not relate to the HJ.

“1. Early Christians believed in Jesus’ (physical, bodily) resurrection.”

How early? How many early Christians believed in a “spiritual” resurrection?

“2. The best explanation for that belief is the hypothesis of the disciple’s discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb and their experience of postmortem appearances of Jesus.”

No, only the experience of postmortem appearances of Jesus. They would have been just as likely to think of an empty tomb as evidence of grave robbery or a direct ascension to heaven.

“The best explanation for the facts of Jesus’ empty tomb and postmortem appearances is the hypothesis that Jesus rose from the dead.”

But these are not established facts. What reason do we have for believing in the empty tomb? Only that a couple of dodgy old stories tell us about it.

If they were established fcts, the best explantion would be that Jesus wasn’t dead in the firsts place.

I wonder what you all make of the established fact that Jerusalem, shortly after Jesus’ death, was filled with the living dead. We have testimony to that in Matthew 27 52-53 “The tombs broke open. The bodies of many holy people who had died were raised to life.They came out of the tombs after Jesus’ resurrection and went into the holy city and appeared to many people.” Just imagine the consequent consternation and chagrin.

Why this well attested fact with “many people” as witnesses isn’t taken more seriously is a mystery to me. I dare not say that this sort of scenario is becoming more and more common in contemporary pop culture TV and movies. But if you think that people today are not eager to have their cities filled with the walking dead, I am sure that people back then weren’t thrilled by the prospect either. That the dead should stay dead and not come walking back is probably as universal a cultural belief as is the incest taboo.

Thomas Paine had fun wiht this idea in The Age of Reason. He asked what happened afterwards? Did they ask for their property back? Did they die natural deaths later?

What I find interesting is that they were resurrected, and their tombs opened, when Jesus was crucified, but they didn’t go back to the city until after Jesus was resurrected. I presume they just sat around in their tombs playing cards and making sarcastic remarks to passers-by. Did they get hungry, and, if so, how did they get pizza in an age without mobile phones?

And absolutely nothing follows from this! Weird events accompanied Jesus’ death, the streets are full of sarcastic zomibes, but when the guard tell the priests that they saw an angel open the tomb, not one of the priests seems to say “Er … hang on a minute, lads. Do you think this Jesus guy just might have actually…”

Consistent use of Craig’s criteria means that we would have to accept the account of the much delayed “resurrection” of Rip van Winkle as a verified fact of colonial American history, and not merely a story created by Washington Irving. How can the van Winkle tale not be true since it is filled with so much confirmatory historical and geographical detail, just like the gospels?

What the literal believers of the Christ myth don’t seem to get is that their formative cult texts, the gospels, are “just-so” stories that were created to explain the myths and legends inherited from the previous generation of Christers.

William Lane Craig is a credulous nincompoop who seems to be incapable of distinguishing between a real history (for example something by Tacitus or Veilleius Paterculus or Sallust, or even the scandal sheets of Suetonius), and a ripping good novel (the gospels, the Satyricon or the Golden Ass). One wonders if he has actually read any of the classical literature, or if he actually believes that every text that came out of that period is “true”, and not a work of the imagination designed for entertainment purposes. In either case, someone that gullible or incapable of real analytic thought should not be teaching at any reputable educational institution.

Craig’s arguments are just as bad as T.S. Elliot’s, they impress the unschooled or the fuzzy wishful thinkers, but are based on severely flawed premises and straw man arguements.

Craig has produced a lot of high sounding piffle and deserves a loud raspberry

(PS

At Mr. Craig:

if you hold the contradictory gospels to be true, then do you also accept the truth of the Mormon Tablets, the more recondite revelations of the Koran, and the foundation story of Scientology as true? The arguments for the later three are just as strong, if not stronger than those you present for the resurrection.)

To become a doctor (medical) in Australia one must also take a minimum number of non-medical units, say from history. At least that used to be the case in my student days. The idea, I was told, is to try to guard against producing a lot of almost monomaniacal Doc Martins, unable to relate to the real world. It would seem to go without saying that to understand the literature of early Christianity one must be more than tangentially familiar with other literature and thought of the time. Sometimes reading New Testament scholarship is like entering a world where one has to leave to one side so much of what one knows from other studies and learn to accept sets of rules that make these studies exceptional.

Fortunately there are a number of prophets among these scholars who do cry out that their peers have so much to gain if they also studied ancient novels, or ancient philosophy and subculture thought, or modern historiographical principles.

But one cannot help but notice that a little idea like postmodernism certainly has been picked up and zealously embraced by quite a number of these scholars. I find this the most ironical — surely postmodernism represents what many conservative or fundamental Christians would surely oppose ethically. I suppose it is, as Stevan Davies indicates, that many are in an anti-testimonial frame of mind by the time they are taking up these studies. And postmodernism is such a useful tool they can use to justify anti-Enlightenment thought. Miracles really can be placed on the probability continuum. No matter if we only have myths and fiction about Jesus — we can declare even these as the perceived truths historians can use and in so doing set a progressive example for all of 21st century historiography.

So delighted to have ran across this classic Vridar post in time to repost for Easter tomorrow! Love it!

-D