Continuing from Little Known Questions . . .

Continuing from Little Known Questions . . .

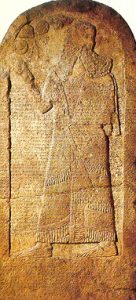

A stone monument constructed by an Assyrian monarch around 850 b.c.e. makes mention of the biblical king of Israel, Ahab, and another king named in the Bible, Hadadezer of Syria. This is the famous Kurkh stele.

The Assyrian king, Shalmaneser III, uses this stone to boast of a victory at the Syrian city of Qarqar on the Orontes River. (See the Battle of Qarqar web page.) It is debatable whether the Assyrian victory was as resounding as the king boasts, but the most interesting detail about the inscription for many is, of course, its mention of Ahab, a Biblical king of Israel.

The stele lists about a dozen kings, led by the Syrian king Hadadezer, who were in alliance against Assyria. The inscription boasts that all these were smashed and routed by the Assyrian forces.

That is, Ahab, the king of Israel whose capital city was Samaria, was in alliance with the Syrian king against the expanding Assyrian empire, and that he suffered a terrible major defeat.

Shalmaneser claims to have destroyed 2,000 Israelite chariots and an army of 10,000 of Ahab’s Israelites fighting alongside Syrian allies.

The curious thing is, however, that in the first book of Kings in the Bible, from chapter 16 on when the story of Ahab begins, Syria is always an enemy of Ahab and Israel. Israel and Syria are at constant war with each other. The attempted Assyrian conquest that brought Ahab and the Syrian king together is simply not mentioned in the Bible at all. In fact, the Bible gives no indication that Assyria emerged on Israel’s horizon until the Second Book of Kings, chapter 15.

Furthermore, the biblical narrative claims that Ahab’s Syrian contemporary was not Hadadezer (or Adadidri in Assyrian) but Ben Hadad.

There are other Assyrian monuments, too, such as the Black Obelisk. They inform us that the Assyrian kings Shalmaneser and Adad-nirari III eventually did conquer all of Syria and Palestine. Joash, king of Israel, is said to have paid tribute to Assyria.

According to the plot of the Biblical history, however, there is no such conquest of Israel. It never happened. Assyria, as mentioned above, is a late entrant in the drama of the Bible’s Primary History of Israel. Assyria’s role is to punish and remove Israel from the map for her sin against Yahweh. Before then, Israel is said to have been periodically punished through intermittent warfare with neighbouring Syria. Key players in this drama are the prophets Elijah and Elisha. Elisha even oversees the blinding of a Syrian army and leads them into the capital city of Samaria.

Unless the Assyrian monuments are completely fabricating campaigns and victories they never fought or won, we are left to think that the author of Kings has taken historical names and re-written them into a theological drama that was the work of his own creative imagination.

Shakespeare did the same with Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, and with Lear, legendary king in Celtic Britain, names and settings he could draw on from historical chronicles and use as vehicles for his own dramatic themes.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Here’s a possibly stupid question – could this be an example of the authors of the OT projecting current or recent history back onto previous eras? I know that they did this fairly often with places – putting in the names of places that didn’t exist until centuries after the events being chronicled were supposed to have occurred. I’ve just started my layman’s journey into biblical history, and I’m still finding myself confused by all the possible timelines for authorship, so I’m not sure if this idea makes any sense or not.

A number of historians have indeed suspected that the biblical “histories” of Joshua and David’s conquests were written as justifying propaganda for the Maccabean conquests. The themes of leaving a settled major power and traveling as sojourners and finding oneself a “stranger” or intruder in another land whose inhabitants must be separated from oneself (e.g. Abraham), it has been argued, were written to support new identities of peoples who migrated (perhaps under ostensibly “benign” coercion) from Mesopotamia and other regions to establish a new colony in Canaan as Persian deportees. (There were also “exoduses” from Egypt around this time, too.)

Richard Friedman wrote a book “The Hidden Book of the Bible” in which he attempts to reconstruct the original “history” from the J strands in the OT but his historical narrative is only full of holes and inconsistencies, arguing against the notion that the Bible was a composite of earlier “histories”.

But histories very generally, among all cultures, reflect the ideologies, interests, values and beliefs of those cultures that produced them.