I suspect one part of the reason some find evolution difficult to accept is their failure to appreciate “deep time”. We can have some notion of “deep space” by looking out at the stars and through telescopes and seeing the evidence of incomprensible distances. But to appreciate “deep time” when we can only know human history of a few thousand years is not so “easy” to grasp. The evidence tells us that species have evolved through time – but we need to think of deep time. It is somehow easier for us to imagine space extending for light years into the distance than to appreciate what is meant by a few hundred million years back in time.

But the evidence is there and cannot be denied (at least not scientifically). One small facet of that evidence, from Why Darwin Matters by Michael Shermer:

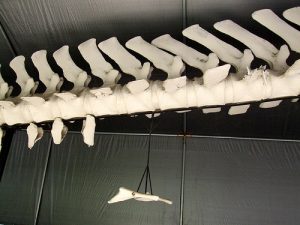

“Vestigial structures stand as evidence of the mistakes, the misstarts, and, especially, the leftover traces of evolutionary history. The cretaceous snake Pachyrhachis problematicus, for example, had small hind limbs used for locomotion that it inherited from its quadrupal ancestors, gone in today’s snakes.

“Modern whales retain a tiny pelvis for hind legs that existed in their land mammal ancestors but have disappeared today. Likewise, there are wings on flightless birds, and of course humans are replete with useless vestigial structures, a distinctive sign of our evolutionary ancestory. A short list of just ten vestigial strucutures in humans leaves one musing: Why would an Intelligent Designer have created these?” (pp 17-18)

“Modern whales retain a tiny pelvis for hind legs that existed in their land mammal ancestors but have disappeared today. Likewise, there are wings on flightless birds, and of course humans are replete with useless vestigial structures, a distinctive sign of our evolutionary ancestory. A short list of just ten vestigial strucutures in humans leaves one musing: Why would an Intelligent Designer have created these?” (pp 17-18)

1. Male nipples

“Men have nipples because females need them, and the overall architecture of the human body is more efficiently developed in the uterus from a single developmental structure.”

2. Male uterus

“Men have the remnant of an undeveloped female reproductive organ that hangs off the prostrate gland for the same reason.”

3. Thirteenth rib

Most humans have 12 sets of ribs, but 8% of of us have a thirteenth set, just as chimps and gorillas do. We share a common ancestry with chimps and gorillas, and our 13th set is retained from the time chimps/gorillas and human lineages branched apart 6 million years ago.

4. Coccyx

This tailbone is all that is left of the tails our common ancestors had for grasping branches and maintaining balance.

5. Wisdom teeth

Before the discovery of tools and fire, hominids were primarily vegetarians. Chewing lots of plants required an extra set of grinding molars. Today our jaws are smaller, but many people still have the extra teeth.

6. Appendix

“This muscular tube connected to the large intestine was once used for digesting cellulose in our largely vegetarian diet before we became meat eaters.”

7. Body hair

Another leftover from our ancestry with thick-haired apes and hominids.

8. Goose bumps (Erector pili)

“We retain the ability of our ancestows to puff up their fur for heat insulation, or as a threat gesture to potential predators.”

9. Extrinsic ear muscles

Some of us, including yours truly, can wiggle our ears. Our primate ancestors “evolved the ability to move their ears independently of their heads as a more efficient means of discriminating precise sound directionality and location.”

(Okay, so what about those people who can curl their tongues and cross their eyes??)

10. Third eyelid

“Many animals have a nictitating membrane that covers the eye for added protection; we retain this “third eyelid” in the corner of our eye as a tiny fold of flesh.”

“Many animals have a nictitating membrane that covers the eye for added protection; we retain this “third eyelid” in the corner of our eye as a tiny fold of flesh.”

.

There are dozens more. Everyone knows our backs were not designed right. Neil Shubin’s Your Inner Fish includes discussions on how evolutionary genetic studies can help identify specific malfunctions that cause certain modern deformities and illnesses — and how such knowledge can help find treatments and cures.

The above are from pp 18-19 of Michael Shermer’s Why Darwin Matters (2006)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!