How do we go about finding a date for when the Book of Revelation was composed?

Many have dated the work to just prior to the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, others date it to the time of Domitian in the 90s: I set out the main reasons for each of those dates in recent posts (see links in side box). I think there are some strong arguments for dating the work to the 130s but before I go there let’s address the various factors that have been brought into play to date the work.

(By the way, some have suggested that Revelation grew piece by piece as a result of different authors over a period of time adding new sections. For my purposes here I am siding with those who have disagreed and see enough linguistic evidence to think of a single author even though that author drew upon a number of sources.)

The legend of Nero redux or Nero redivivus

Revelation speaks of a return of some sort of monstrous ruler after he had once been thought dead or simply out of the picture for some reason. We think of the many hopeful people in the eastern part of the Roman empire who long believed that their beloved Nero, after news of his suicide, was still alive and would return.

The links here take interested readers directly to the sources that testify to beliefs that Nero would return.

The Nero myth of return was still going strong in the eastern part of the empire into the second century. The historian Suetonius tells us that twenty years after Nero’s death there were many who enthusiastically believed the claims of one claiming to be Nero. Dio Chrysostom, writing between 90 and 110 CE, noted that most people in his region believed Nero was still alive. The satirist Lucian was able to remind readers of his own day, in the 140s CE, that those from their grandparents’ times had believed Nero would return. The Sibylline Oracles contain prophecies of Nero’s return: the relevant passages in book IV describe the eruption of Mount Vesuvius so are understood to have been written between 80 and 90 CE; those of book V as late as 130 CE since they refer to the Jewish uprisings throughout the Diaspora between 115-117 CE. (See also a discussion on the Reading Acts blog for the dating of these oracles.)

Emperor Worship in Asia Minor

The setting of Revelation is the Roman province of Asia (note the opening address to the seven churches). If Revelation is warning the faithful not to succumb to pressure to “worship the beast” (think of sacrifices to the Roman emperor) then it would be good to know what was happening, and when it was happening, with respect to emperor worship in that region. One scholar, Klaus Berger, has claimed that in the years leading up to 70 there was an “intensive blossoming of cultic emperor worship in Asia Minor”. On the other hand, Steven Friesen writes “The period of Nero seems to have been rather quiet with regard to imperial worship.” The evidence cited indicates that a revival of this cult had to await the consecration of a dedicated shrine in Ephesus in 89/90 CE.

666 – the number of the beast

Certainly, the number 666 is known to match the emperor Nero. However, Nero is not the only candidate whose name adds up to 666. Irenaeus himself wrote of different possible interpretations. (We will see in future posts that Revelation 13:18 can be understood to direct readers to two different persons and that one should be interpreted in the light of the other, that the man Nero returned as the beast in another emperor.)

The seven kings of Revelation 17

It appears that everyone has a method to identify these seven kings. That there are so many different interpretations (some starting with Julius Caesar, some with Augustus, some with Claudius; some omitting the three emperors of the year of the civil war, others including all or only one of them, and so forth) pretty well eliminates the possibility of using them as a guide to dating the work.

The destruction of Jerusalem

In Revelation 11 we see the two witnesses active in Jerusalem and the author is told to measure the temple there. Unfortunately, that scenario has not been enough to persuade everyone that it was written before 70 CE. As one commentator on the book wrote, “The 11th chapter [of the Apc] belongs to the darkest pieces of the Rev”.

In touch with early theology (e.g. Paul’s teachings)

Some have noted how close Revelation appears to be in relation to Pauline theology and the older (Q) tradition behind the gospels. It does not follow, though, that the work should be dated as early as those sources; the most we can say is that the author knew of Paul’s writings and the gospels.

The earthquake of Laodicea in 61 CE.

Revelation describes the church at Laodicea as being rich and comfortable. Since Laodicea was levelled in 61 by an earthquake could it have been rebuilt as early as 68/69? Some think so.

Church hierarchies

There is no obvious appearance of hierarchical structures in church governance in Revelation. That could suggest an early date. It could also suggest that hierarchies were taken for granted as they were at a later time.

Time of war and crisis

The author anticipates the fall of Roman power so the “civil wars” of 68/9 seem to fit such a time. However, keep in mind the setting of the Roman province of Asia: those battles had no effect in that region and would hardly have generated a sense of crisis there. The same applies to references to fears of a Parthian invasion. Those fears were extant throughout the period from 45/50 to 155/160 CE so cannot be used as a clear indicator for dating.

Persecutions – Nero and Domitian

Revelation does appear to speak of a time of organized state persecution of Christians. If we accept the accounts of the Neronian persecutions of Christians as historically credible we are still left with the fact that that was a one-off event. It was past history by the time Revelation was written. As for the persecutions of Christians in the time of Domitian, scholars have been obliged to conclude that the evidence there is very thin. There are some late reports of individual cases but nothing to suggest an organized program to suppress Christianity. Besides, we need to be careful about what Revelation actually depicts as historical on the one hand and what it anticipates in the future on the other.

Twelve apostles and Babylon

Revelation presents the twelve apostles as the foundation of the new Jerusalem and uses Babylon as a cipher for Rome.

Critics of a date prior to the destruction of the temple in the year 70 claim that the notion of “twelve apostles” being the foundation of the church is unlikely to have been extant so soon. Similarly, critics have said that Babylon would only have been used as code for Rome after it had destroyed Jerusalem.

A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine!

Thus says the voice at the appearance of the black horse.

Did Domitian issue an edict that sought to regulate the disproportion between wine and grain cultivation in the empire? Some think there is evidence that he did, but it is far from certain that any such edict was issued. If it had been then it appears to have been only a temporary measure. There is precious little evidence that such an event happened or that it had any appreciable impact in the province of Asia if it did.

Testimony of Irenaeus

Irenaeus is thought to tell us that John wrote Revelation in the time of Domitian. Given that Irenaeus wrote around 180 CE, that testimony can only have historical weight if it can be shown that behind the claim there is an oral or written tradition that dates back close to the time of the writing of Revelation.

The arguments set out on the one hand for the nature of sources used by Irenaeus are lengthy; so are the arguments that examine the grammatical structures used by Irenaeus, the differences between the Greek and Latin versions of the key passages, and discussions on what conclusions we can draw from all of that detail. Bypassing all of that material here, I will only note that it appears certain that Irenaeus had a habit of citing his sources wherever possible to add weight to his work, and that when he did not do so, we have reason to believe that his statements were conclusions he drew from his own reasoning and assumptions.

…o…

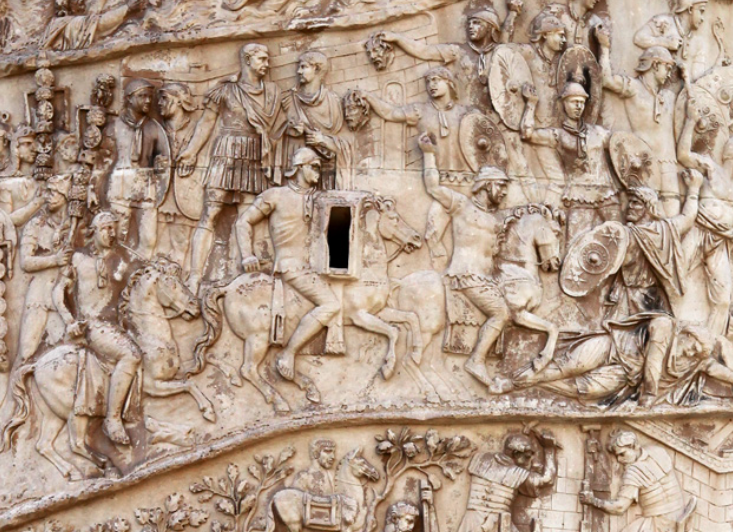

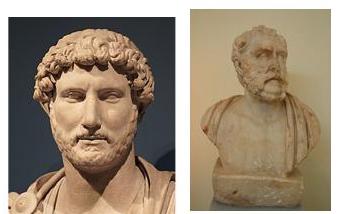

Next up, we’ll look at some preliminary reasons for thinking Revelation was a response to Hadrian in the 130s.

Witulski, Thomas. Die Johannesoffenbarung Und Kaiser Hadrian: Studien Zur Datierung Der Neutestamentlichen Apokalypse. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007. http://www.librarything.com/work/5467644/book/208189148.

Like this:

Like Loading...

My intent in this post is to give an overview of the key points argued by Thomas Witulski [TW] in Part 2 of The Revelation of John and Emperor Hadrian [translated from the German: Die Johannesoffenbarung und Kaiser Hadrian]. I include links to works that he critiques so you can follow up the other side in their own words.

My intent in this post is to give an overview of the key points argued by Thomas Witulski [TW] in Part 2 of The Revelation of John and Emperor Hadrian [translated from the German: Die Johannesoffenbarung und Kaiser Hadrian]. I include links to works that he critiques so you can follow up the other side in their own words.